In Lone Pine, a lawyer fights to change campground’s derogatory name. The town pushes back

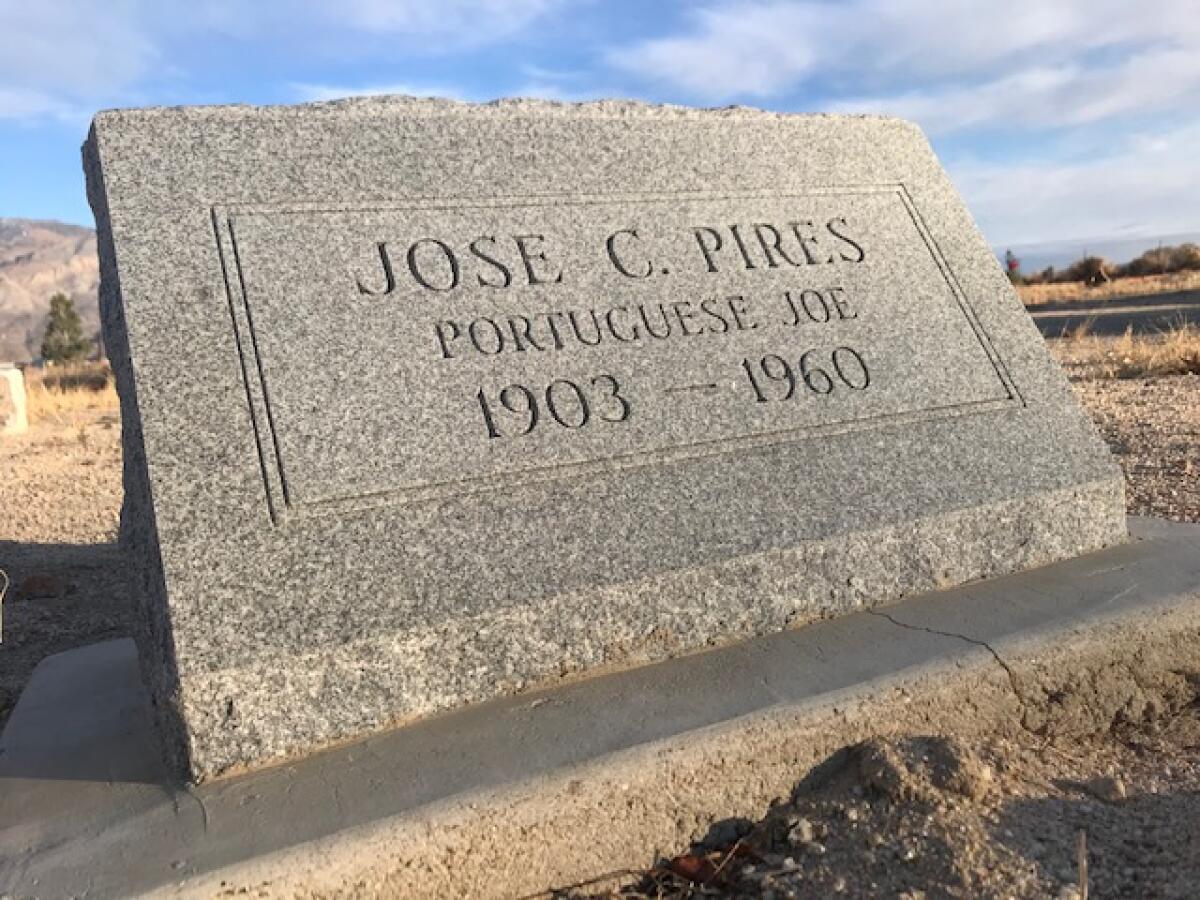

LONE PINE, Calif. — Storm clouds gathered over eastern Sierra Nevada peaks on a recent weekday when Allen Berrey spotted a modest granite headstone engraved with the name Jose C. Pires.

It was a crummy day to visit Mt. Whitney Cemetery, but Berrey had a reason to spend it among hundreds of grave sites decorated with small American flags and flowers.

He stepped up to introduce himself. “Hello there, Joe,” he said, with a toothy smile. “I’m a lawyer, and I’m not going to let folks call you derogatory names anymore.”

Berrey reached into his backpack and pulled out a bottle of port. He poured a little into a paper cup. Raising it, he said, “Salud!”

* * *

Lone Pine is an Owens Valley town where Hollywood filmed many of its westerns, including some involving an outsider arriving to take on the powers that be. Berrey could be one of those characters. He has made it his mission to restore honor to Pires, who is memorialized at a Lone Pine campground that was long ago named “Portagee Joe.”

Until he died in 1960, Pires was just one of the many tramps who camped on the western edge of town. Good-natured and hospitable, he had a reputation as a local Robin Hood who stole turkeys from neighboring ranches during Christmas week to give them to needy families.

He became known as Portagee Joe, a slur adopted from a Portuguese character in John Steinbeck’s 1935 novel “Tortilla Flat.”

Apparently, few in Inyo took offense in the 1960s when the county tore down Pires’ crude homestead on Lone Pine Creek and named it Portagee Joe Campground.

California is dotted with numerous racially offensive place names, many of them holdovers from the Gold Rush. Near Sacramento, a group has petitioned to change the name of Folsom’s Negro Bar Recreation Area, sparking debate on whether the name is “out of date” or instead relevant to the site’s history.

In Lone Pine, Berrey has come under personal attack for wanting to rename it for something that is “more respectful and dignified,” as he puts it. In a community where distrust of big change runs deep, many residents and county officials say the existing name captures a moment in history and is appropriate for a local Portuguese man, who, according to some, didn’t seem to mind the moniker.

“We called him Portagee Joe and he liked the attention,” recalled Kathleen New, 75, executive director of the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce, who is strongly opposed to the proposed name change. “It wasn’t a derogatory slur to him.”

“Allen Berrey, however, is a moron,” she added. “What right does he have to come into our valley and change our history?”

In New’s corner is Michael Prather, a Lone Pine resident and prominent environmental activist. “The county has many pressing matters more deserving of its attention than this,” Prather said.

Born and raised in Yosemite National Park, Berrey has always stayed close to the high peaks of the Sierra. In Yosemite, his father was a marketing director for a park concessionaire and his mother was a ranger. To this day, he prefers logging clothes over suits, and often dons a black Dorfman-Pacific Scala Classico “Sierra” hat that, he likes to say, is “something John Muir would wear.”

Although labeled an outsider, Berrey has lived in Inyo County since 1997, often championing underdogs.

For nearly two years he was a county public defender in Inyo, home to 16,000 people. “I mostly represented young men — many of them Paiute Indians — who were put in shackles in detention cells,” he said.

In his current campground crusade, Berrey initially presented the county with a compromise solution he felt would respect local history and show empathy for the feelings of Americans of Portuguese descent: change the name to “Portuguese Joe.”

Upon further consideration, however, Berrey nixed that idea. That name, too, he decided, would be inappropriate for a publicly-funded campground.

Kevin Carunchio, who was Inyo County administrator at the time, sought to end the furor with an official compromise of his own: keep the existing name, but add historical information about how it became attached to the campground.

But that change never came about, prompting Berrey this month to launch a new offensive, which goes beyond lobbying Inyo County supervisors to take up the matter. He notified both Inyo County and the owner of the campground land, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, of his intent to sue.

“In the local vernacular: I have a burr under my saddle — I want the name changed,” he said. “Right now, the county is perpetuating a racial slur, which is a perverse way to honor the man.”

The lawyer informed Clarence Martin, aqueduct manager for the Los Angeles utility, that the lease agreement “contains LADWP’s requirement that Inyo County not engage in any form of discrimination in its operation of the campground.”

“The county’s use of the pejorative word ‘portagee’ in the name of the leased campground site is an act of discrimination against a group of persons based on national origin; and it is therefore a violation of the referenced antidiscrimination covenant in the LADWP-Inyo County lease,” he wrote, adding that the county’s expenditure of funds to operate Portagee Joe Campground is therefore illegal.

Anselmo Collins, director of water operations at the LADWP, would not go that far. “We are not supportive of any derogatory slur,” he said in an interview. “The name of that campground is not a good thing ... but it is a county campground.”

In a county where LADWP owns most of the land and water and has a grip on the region’s economic stability, the dispute has left Inyo County Supervisor Matt Kingsley, whose district includes Lone Pine, in an awkward position.

“With a lawsuit threatened against Los Angeles and the county, I have to be careful,” he said. “But I also need more time to deal with this. That’s because I have a whole town that wants the name to stay the same.”

Racial tensions have long simmered in the 180-mile-long Owens Valley, starting in the 1800s, when U.S. troops were sent to protect settlers and the land and water they had effectively stolen from Native Americans.

In 1863, settlers and soldiers chased 35 Paiute Indians into Owens Lake, just south of Lone Pine, to drown or be gunned down.

About seven miles to the north, in the shadow of Mt. Whitney, is the Manzanar internment camp, where U.S. authorities detained thousands of Japanese Americans during World War II.

After the turn of the last century, Pires joined the stream of Portuguese immigrants escaping depressed economic conditions in the Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Cape Verde and Madiera. Like many others, Pires found his way to the mountain communities of the Sierra Nevada, where sheep and mining industries offered a path toward integration into American society.

Pires died on Dec. 8, 1960, of heart disease. Although locals knew him as Portagee Joe, friends or relatives had the headstone engraved with the nickname Portuguese Joe, perhaps as a measure of respect.

A six-paragraph obituary in the Inyo Register newspaper offers what little is known about Pires, who was born in 1904 in the town of San Aras on the island of Treseia, off the coast of Portugal. He came to the United States in 1920, and 21 years later settled in Lone Pine.

During the last eight months of his life, it says, Pires attended the Foursquare Church, where he confided during a testimonial service that “he loved the Lord but wasn’t sure whether the Lord loved him.”

At the conclusion of the funeral service at Mt. Whitney Cemetery, the officiating pastor and a resident on guitar sang Joe’s favorite song, “This World Is Not My Home,” written by Albert Brumley in 1936.

This world is not my home, I’m just passing through,

My treasures are laid up somewhere beyond the blue

The angels beckon me from heaven’s open door

And I can’t feel at home in this world anymore.

Present at the graveside were his friends, the obit said.

* * *

After drinking the toast, Berrey lifted his coat collar and adjusted his hat as the cold wind blew.

“I really don’t understand the animosity over this — it’s not like trying to change the name to Che Guevara,” he said, shaking his head.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.