If a warm U.S. winter was ‘a preview of global warming,’ what part did a polar vortex play?

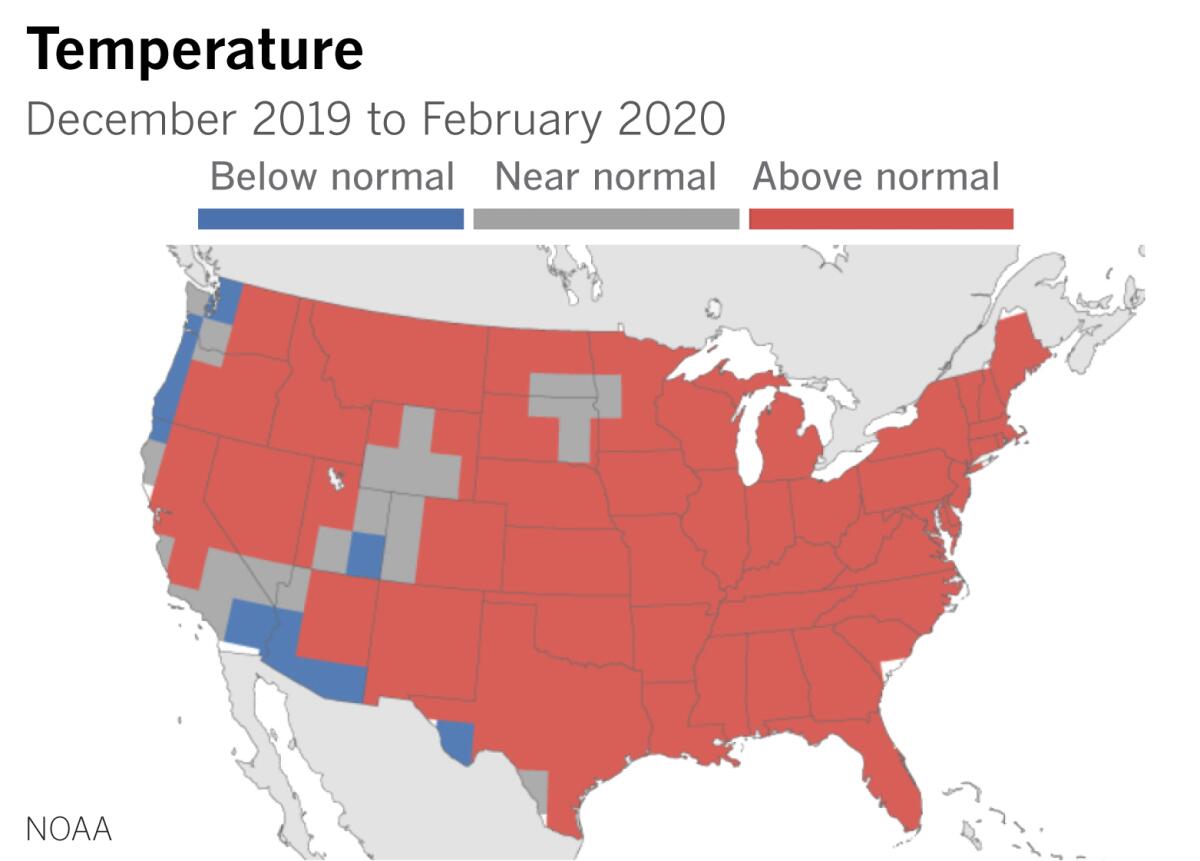

The winter that just ended was the sixth-warmest on record in the contiguous United States, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And one feature of that winter was a strong zonal, west-to-east flowing polar vortex.

Wait, what?

Usually when we hear about a polar vortex, it’s in news stories about frigid temperatures enveloping the U.S.

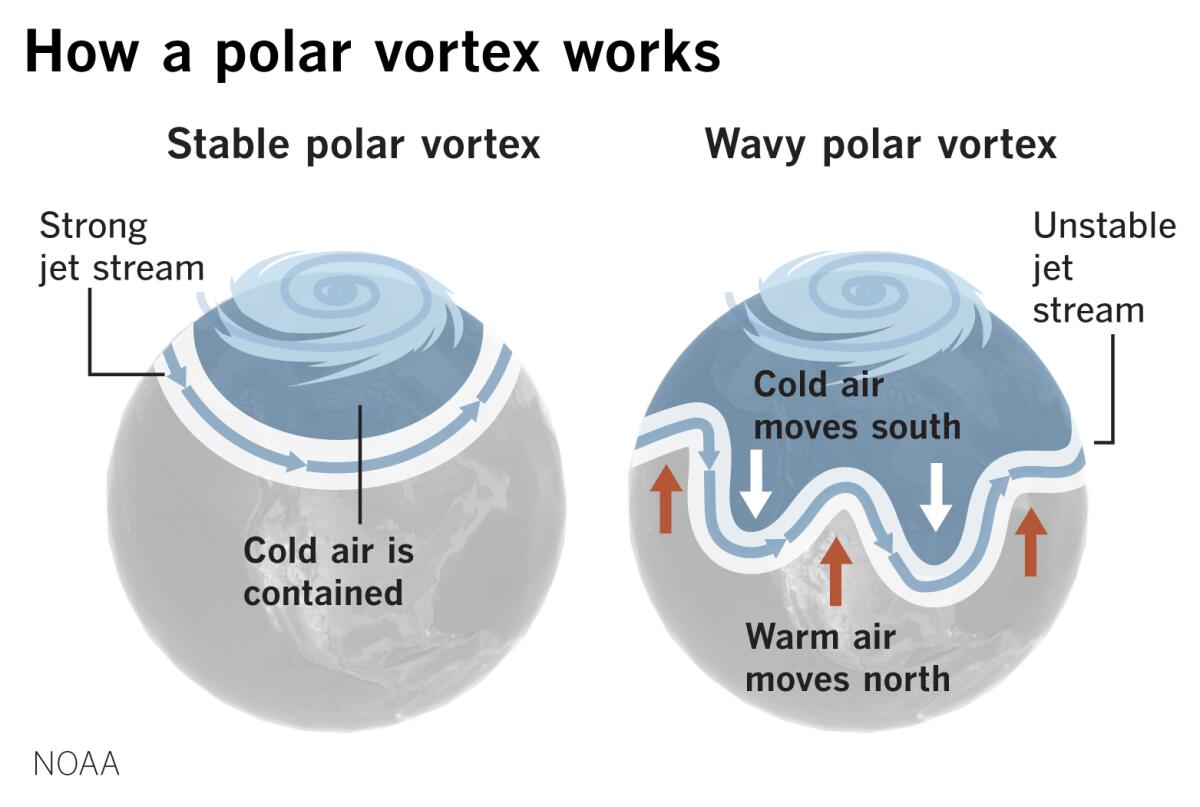

“Polar vortex” became a weather buzzword back in 2014, but it’s not the strong polar vortex that brings Arctic cold down into southern latitudes of the continental U.S. It’s the unstable, wavy one.

A strong, stable polar vortex has been described as a spinning bowl of low pressure over the Arctic region. The edge of that bowl is defined by the jet stream, kind of like salt on the rim of a margarita glass.

The polar jet stream consists of strong, upper-level winds in the mid-latitudes that blow from west to east around the globe. As the jet stream spins around the rim of this bowl, it confines the frigid air to the Arctic. The jet stream tends to remain farther north than usual in this scenario, with warmer air to the south. That’s what happened a lot during the winter of 2019-20, resulting in warm temperatures for the continental U.S.

The jet stream and this cold bowl are in the troposphere, the lowest, densest layer of the atmosphere — roughly the first 6 to 12 miles above the Earth’s surface — where nearly all the weather happens. There’s also a polar vortex in the stratosphere, the next higher level of the atmosphere, which is also edged by another, higher-altitude jet stream. This stratospheric vortex and its winds spend their time essentially making concentric circles around the pole. (These polar vortexes also occur around the South Pole, affecting the Southern Hemisphere.)

Both of these Northern Hemisphere polar vortexes were especially strong this winter, but we’re mainly concerned with the tropospheric polar vortex here, the one that’s in the layer closest to the surface of the Earth.

How can we measure the strength of this polar vortex? One way is the strength of something called the Arctic Oscillation (AO). The Arctic Oscillation is a measure of the stability or instability of the polar vortex. Twice in the month of February, the AO index reached all-time daily highs for strength and stability. The AO for the December-February period was the second-highest since 1950.

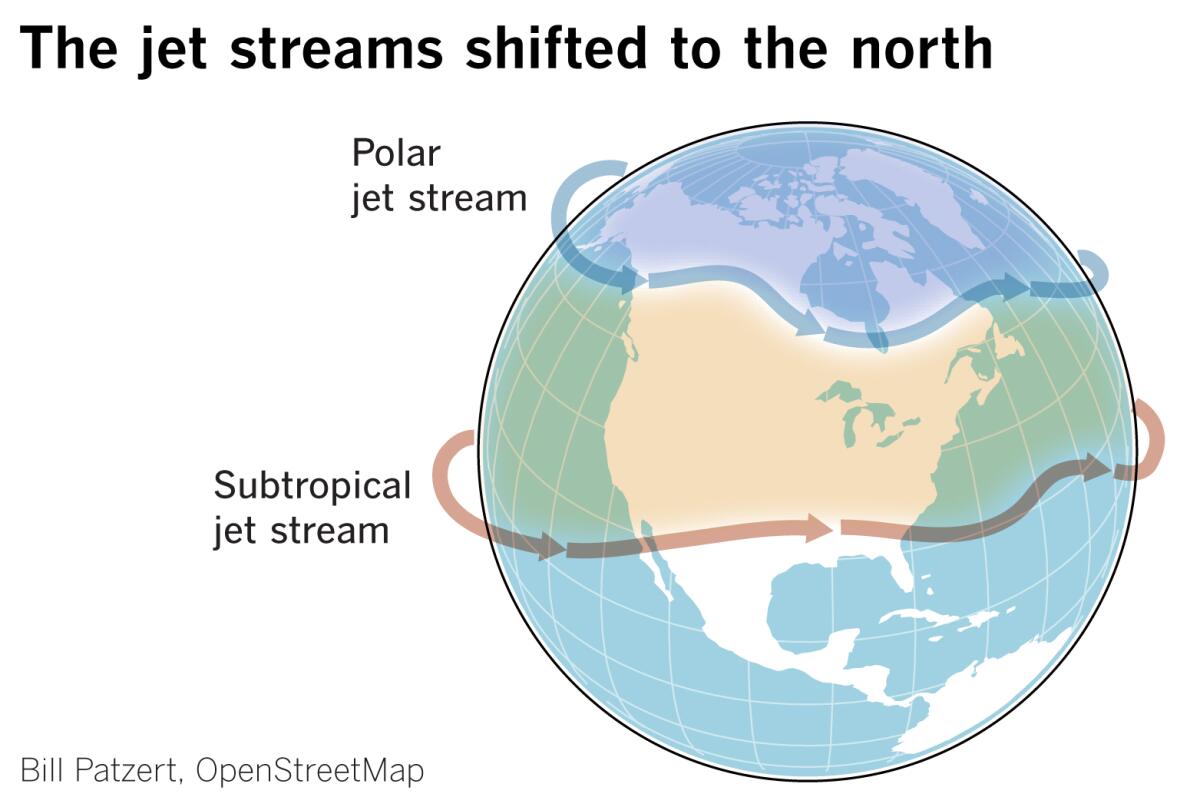

Such a strong AO means the polar jet stream stays farther to the north, and it is “tight, not wavy,” as climatologist Bill Patzert describes it. This configuration resulted in a colder-than-average winter in Alaska and northwestern Canada, and contributed to a warmer-than-average winter in the contiguous United States, said Patzert. “The frigid polar air is locked in the Arctic.”

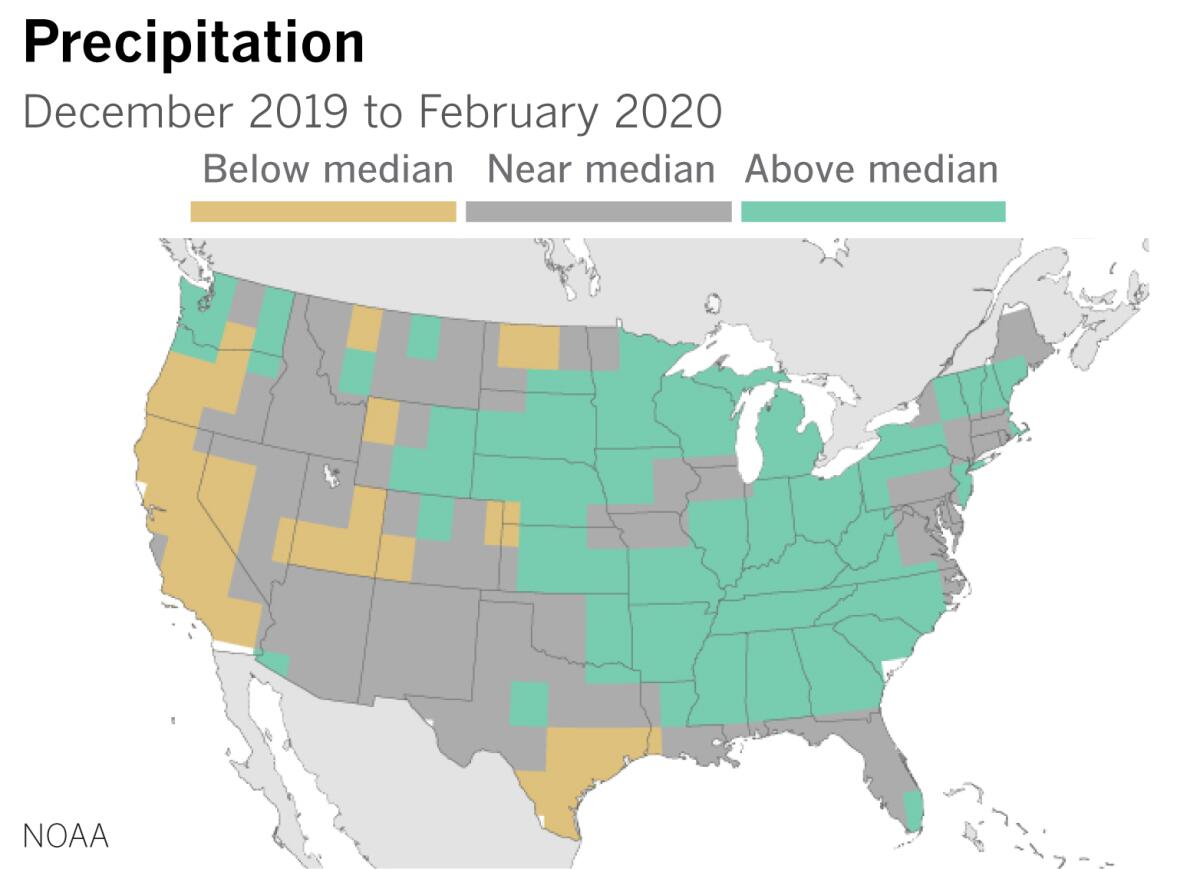

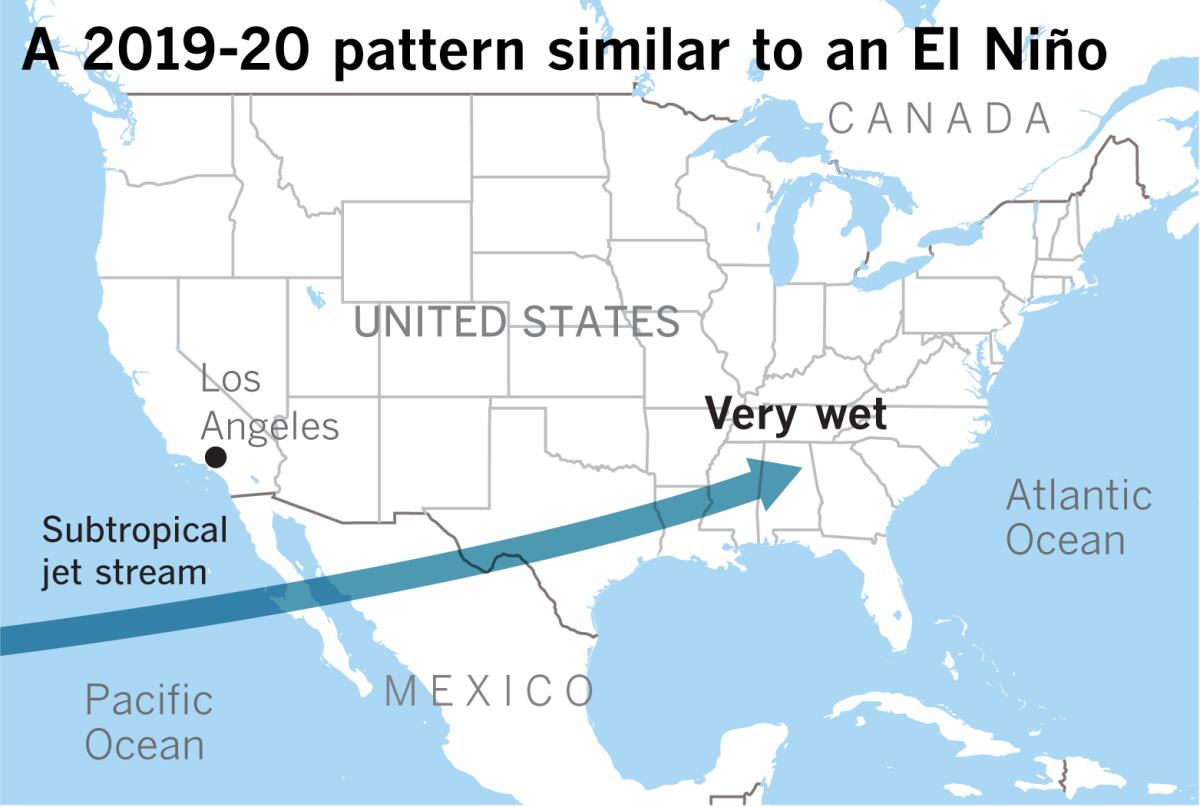

Farther to the south, the subtropical jet stream works hand in hand with the polar jet. Like the polar jet, the subtropical jet stream shifted farther north this year — into northern Mexico, north-central Texas and the northern portions of the Southeastern U.S., Patzert explained.

“This is a preview of global warming. In a warming world, these patterns shift north,” said Patzert. “The subtropical jet stream, which comes out of Southeast Asia and usually peters out around the international dateline, also is a little more active and moves farther north. This year it behaved somewhat like in an El Niño year,” Patzert said. “In an El Niño year, it shifts even more to the north.”

El Niño, also called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), is a periodic warming of sea surface temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean. Since the Pacific is so big, it’s like the 800-pound gorilla of global weather, and such a warming phase affects the whole planet, including, usually, causing a reduction of hurricanes in the Atlantic. It often — but certainly not always — spells a wet winter for California.

El Niño’s opposite, the cooling phase, is La Niña.

Even though this year was neutral — not an El Niño or a La Niña — the subtropical jet plowed into northern Mexico and continued on into the Southeastern U.S., where heavy rain was accompanied by tornadoes and flash flooding. This is behavior that’s more like an El Niño.

An example of a strong El Niño when the subtropical jet shifted north is the 1997-98 season, Patzert points out. It was like a fire hose. Downtown Los Angeles received slightly more than 31 inches of rain — more than twice the average rainfall. The 2015-16 season was also a strong El Niño year, but Los Angeles got only 9.6 inches.

What happened?

“That El Niño had all the prerequisites. Based on previous years, it should have been a no-brainer” that L.A. and California would have a wet year, said Patzert.

As happened with this year’s subtropical jet stream, moisture in 2015-16 streamed to the south toward Mexico. By all appearances, the setup looked like it would be a wet year in California; instead, the rain went deep into the heart of Texas. “It was the wettest winter and spring in Texas history,” said Patzert.

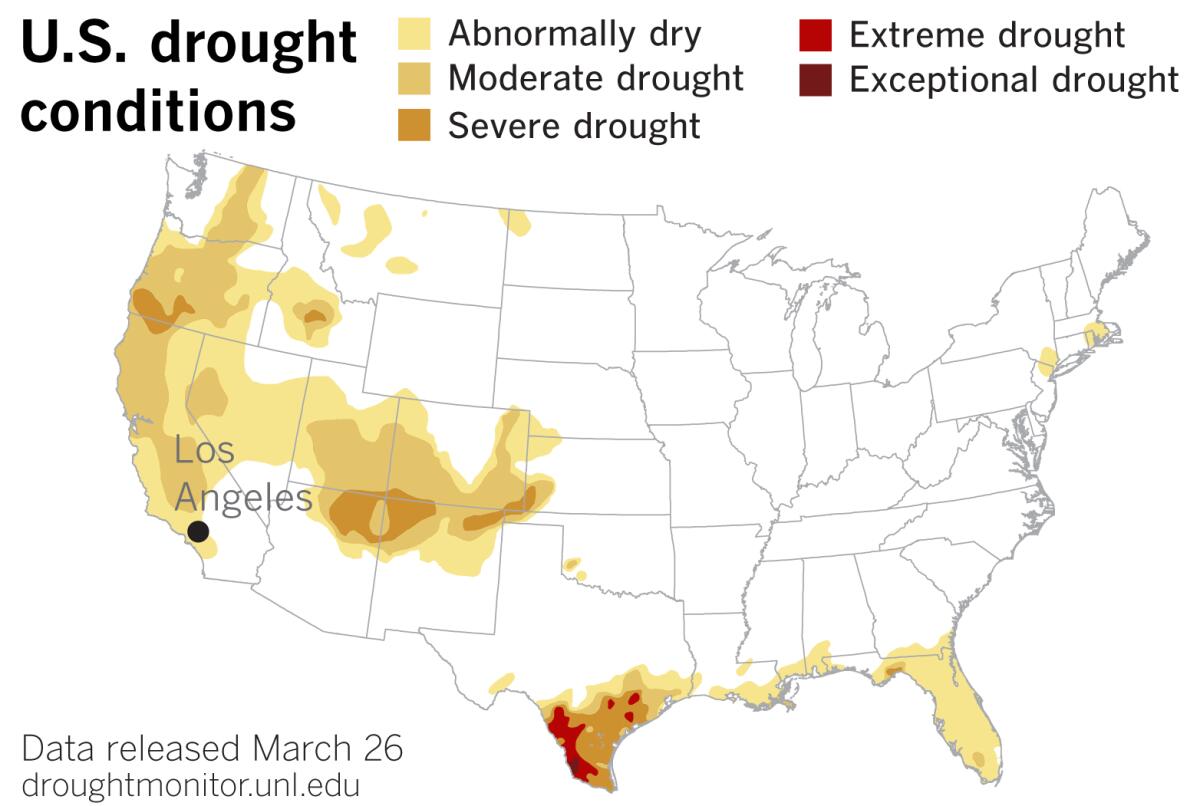

The most recent U.S. Drought Monitor reflects the subtropical jet stream pattern seen this winter. Drought conditions are widespread and expanding up and down the rain-deprived West Coast — even including interior Washington state. The 2019 Southwest monsoon season was one of the hottest and driest on record, according to the National Weather Service, and there’s now severe drought in the Four Corners region, which is part of the Colorado River watershed. But there’s a swath of drought-free territory through central Texas into the Southeast, even as drought conditions have worsened in south Texas, through the Rio Grande Valley, along the Gulf Coast and into much of Florida.

As Brad Rippey of the U.S. Department of Agriculture put it in the most recent Drought Monitor, “The Southeast remains a tale of two landscapes: wet to the north in recent weeks, except in some locations across the coastal plain and along the Atlantic Coast, but dry along the Gulf Coast and in Florida.”

The 2019-20 winter season was on-again, off-again. It started out promising, then turned dry as the polar vortex strengthened. As Jay Lund of UC Davis writes, midwinter turned into a “Flatline February” followed by a “Meh March.” He adds, “With the near-end of its wet season, California’s 2020 water year is and will be dry.”

While the subtropical jet settled in south of the border this winter, high pressure established itself in the eastern Pacific, blocking the storm track and routing storms into the Pacific Northwest or southern British Columbia, then channeling them down into the Rockies.

The systems that managed to come down from the Pacific Northwest farther to the west and closer to the coast were over land, and were dry “inside sliders.”

When high pressure isn’t blocking storms from the Gulf of Alaska, as was the case right after Thanksgiving, the classic pattern sets up for low-pressure systems to tap into a plume of tropical or subtropical moisture and power it into the California coast.

Another way to look at it is viewing the upper-level low and the moisture plume, which is usually congruent with the subtropical jet stream, working together. “All wet winter storms have some of that,” said Eric Boldt of the National Weather Service in Oxnard. “They work in concert.” He likened the interplay to a river, where a little eddy near shore moves out into the channel and joins another strand of the current.

But a blocking high did set up, and in early January meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services in the Bay Area had begun compiling data comparing midwinter dry spells.

After a record dry February in most of California, especially Northern California, March showed some promise, but persistent drought was clearly returning.

A March 10-11 storm featured a cutoff low coming down the coast that was forecast to tap into an atmospheric river and hose down Southern California. The atmospheric river shifted south into Baja California, but the low still managed to pull in some moisture.

Hopes of a “March Miracle” were dashed again.

If the strong, stable polar vortex with the shifting jet streams are a foretaste of things to come with climate change, it doesn’t paint a promising picture. As Patzert points out, the “snowpack comes later and leaves earlier, which has implications for our water supply.”

If the subtropical jet stream shifts to the north and feeds into California, it will be warm and will usually provide precipitation in the form of heavy rain — which will mostly flush out to sea without being captured because it comes so fast. In addition, warm rains will melt any snow on the ground in higher elevations. With such a shift, there will be fewer cold storms that arrive on a polar jet stream from the Gulf of Alaska. Such cold storms bring snow, which is stored in the state’s “biggest reservoir,” as Patzert calls the Sierra Nevada. That allows snowmelt to run off gradually, filling reservoirs and streams throughout the warmer months.

“As for this rain and snow year, the polar vortex seems to have been a spoiler, and it will take more than a miracle to make up for that in April,” said Patzert.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.