Column: It’s a happy Labor Day indeed after NLRB cracks down on employer sabotage of union elections

For decades, employers have felt free to trample workers’ right to organize unions and engage in collective bargaining.

They’ve fired pro-union workers, threatened to close unionizing plants, subjected workers to surveillance and interrogations about their union activities, and posted menacing security guards around locations of union activity.

All these practices are illegal in the context of union organizing drives, but employers have engaged in them with impunity because the penalties have been almost nonexistent.

An employer is free to use the Board’s election procedure, but is never free to abuse it—it’s as simple as that.

— NLRB Chair Lauren McFerran

No longer.

On Aug. 25, the National Labor Relations Board issued a landmark ruling stating that whenever an employer commits an unfair labor practice while its request for a union election is pending, the board will order the employer to recognize the union without an election and move immediately to contract bargaining.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Union advocates believe the ruling, along with an NLRB decision the previous day streamlining unionization votes, will put the kibosh on employer behavior aimed at interfering with those votes or delaying them interminably.

That’s the board’s explicit goal. “An employer is free to use the board’s election procedure,” NLRB Chair Lauren McFerran said after the Aug. 25 ruling, “but is never free to abuse it — it’s as simple as that.”

The ruling underscores how the Biden administration has remade the NLRB to restore its traditional role as a bulwark for labor rights, following years in which that goal was eroded by Republican administrations (especially the Trump presidency) and Democratic inattention. The ruling was reached by a 3-1 party-line vote.

It also reflects a determination by the board’s Biden-appointed general counsel, Jennifer Abruzzo, to reverse a series of rulings by the Trump-dominated board that had “overruled legal precedent,” as well as older rulings she wished to “carefully examine.”

Hundreds of workers have died from extreme heat, but business lobbyists insist government rules aren’t necessary. Workers’ best hope for protection: unions.

The new ruling may sound legalistic, but in practice it’s simple.

Under the National Labor Relations Act, passed in 1935, when a majority of a company’s workers sign union affiliation cards, the company has two choices: recognize the union outright and proceed to bargaining, or ask the NLRB to run a union representation election.

It’s during the run-up to elections that unions tend to lodge accusations of unfair labor practices against employers. Employers try to delay the elections as long as possible, “aiming to gain time within which to undermine the union,” the board observed.

That’s what happened in the case that produced the latest ruling, which was brought by the Teamsters against Cemex Construction Materials Pacific, a concrete mixing and hauling firm operating in Southern California and Nevada.

In late 2018, at least 207 of the firm’s drivers, or 57%, signed authorization cards designating the Teamsters union as their bargaining representative. An election was scheduled for March 2019.

The company moved “quickly and aggressively” against the union, according to the NLRB. It hired the Labor Relations Institute, a prominent union-busting consulting firm, for more than $1.1 million. It ginned up a disciplinary case against a driver who was a leading union activist and eventually fired her.

It peppered workers with threats of what would happen if they unionized, implying that unionized plants would be closed, leaving the workers permanently unemployed. It forbade workers to talk to union representatives “on company time,” including downtime.

Republicans are bowing to industry lobbyist in loosening state child labor laws. The inevitable result will be a rise in child deaths in the workplace.

In all, the NLRB found Cemex to have committed “more than 20 distinct instances of objectionable or unlawful misconduct.” These efforts bore fruit. The union lost the representation election.

The board found, however, that the company had effectively crossed “the fine line between lawful persuasion and unlawful coercion.” It also found that several high-level company officials lied to the administrative law judge to hide the company’s lawbreaking.

A Cemex spokesperson told me by email that the company was “disappointed” by the NLRB decision and was “evaluating next steps.” The spokesperson said, “We remain committed to providing the best working environment and to complying with all labor laws and fair practices” and the ruling “does not affect that commitment.”

According to an NLRB standard implemented in 1949, the board could have ordered the company to recognize the union and start bargaining. But that standard, known as the Joy Silk rule after the textile mill that produced it, was abandoned in the course of a Supreme Court case in 1969.

Under the original rule, an employer could refuse to recognize a union and demand an election only if it had a solid reason to doubt that the union had really achieved a majority, not merely to reject collective bargaining rights or to undermine the union.

The change left the board with only one real remedy against employer efforts to undermine unionization elections — to schedule a new election. That plays into employers’ hands, because delays almost always work in their favor.

Indeed, NLRB statistics show that unfair labor practices soared after the Joy Silk rule was abandoned in 1969. Over the following decade, accusations of illegal firings increased from 8,122 to 18,313 and charges of illegal intimidation of unionization advocates from 947 to 6,493.

Julie Su’s accomplishments make her a spectacularly qualified nominee for Labor secretary. That’s exactly why Republicans — and some Democrats — will do their best to block her confirmation.

“The NLRB relinquished its capacity to effectively deter the commission of [unfair labor practices] during union organizing campaigns,” Brian J. Petruska, a lawyer associated with the Laborers’ International Union of North America, wrote in a 2017 study the board cited in its Cemex decision.

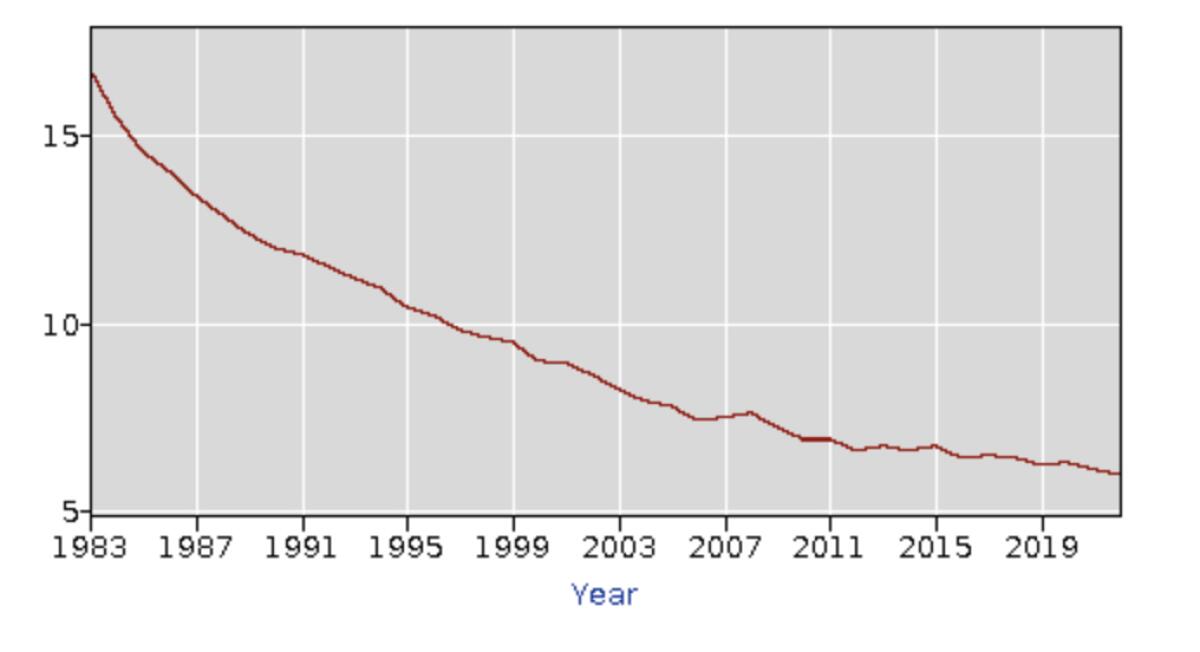

The NLRB’s action surely contributed to the long-term decline of union membership, which has fallen in the private sector to 6% of wage and salaried workers in 2022 from 17% in 1983. (It peaked in the 1950s at about 33%.)

The Cemex ruling effectively restores most of the Joy Silk rule. The board found that the company “would likely meet a rerun election with a similarly aggressive union-avoidance strategy, similarly prone to stray into unlawful coercion.”

Accordingly, it ordered the company to start bargaining with the union, with no formal election necessary. It also ordered the company to reinstate the fired driver, with back pay.

Although the Cemex case heralds the restoration of a long-overdue pro-labor outlook on the NLRB, that rests on a knife edge. As Harold Meyerson observed in The American Prospect, the board has just lost its ability to issue any decisions revising its rules.

That’s because the term of one of the Democratic members, Gwynne Wilcox, expired on Aug. 27. Biden has nominated her to another term, but the Senate hasn’t yet acted — and recently, even with its narrow Democratic majority, has shown itself to be willing to take an anti-labor stance, such as when Big Business challenges nominees to the Department of Labor. A confirmation vote is expected early this month, however.

David Weil would have enforced federal labor law leading the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division, so Republicans killed his nomination.

By long-standing practice, the NLRB comprises three members from the president’s party and two from the opposition, but one Republican seat has been vacant and the GOP has yet to offer a nominee. Until Wilcox returns, the board is bereft of a decision-making quorum. The Cemex and the previous decision were plainly timed to beat the end of Wilcox’s term.

And if the GOP takes back the White House in 2024, Republicans are sure to undo all the progress made by Abruzzo and the current Democratic majority.

Meyerson is right to note that the Cemex ruling will strengthen the hand of the Teamsters, United Auto Workers and other unions undertaking strong organizing campaigns in the industrial heartland and in the union desert of the Southeast.

It’s also a shot across the bow of the obnoxiously anti-labor Starbucks, which earlier was found by an NLRB judge to have committed “hundreds of unfair labor practices” in its fight against unionization drives by its baristas. The NLRB landed on Cemex like a pile of bricks, and that company was found to have committed only a couple of dozen violations. What’s in store for Starbucks?

In general, there’s reason to be optimistic about collective bargaining rights on Labor Day this year. But no reason for union organizers to take their eyes off the prize, either. Organizing opportunities like these don’t come around often, or last forever.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.