Column: The carnage from the rollback of child labor laws is just starting

If there is a predictable outcome from the rollback of child labor laws now taking place in red states nationwide, it’s that a flood of injured children is on the way. We are now standing on the edge of the water.

In just the last week, reports of horrific child deaths have come from Mississippi and Wisconsin. In the first case, a 16-year-old Guatemalan boy was killed at a poultry plant in Mississippi. In the second, a 16-year-old boy was killed when he got pinned in a wood-stacking machine at a sawmill.

What may be most horrifying about these accidents is that the work the children were doing is illegal under the laws of both states. But they happened amid a nationwide push by manufacturer and restaurant lobbies to liberalize child labor laws in those states and elsewhere.

With this legislation Iowa joins 20 other states in providing tailored, common sense labor provisions that allow young adults to develop their skills in the workforce. In Iowa, we understand there is dignity in work.

— Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, signing a rollback of child labor protections

In April, I reported on this campaign to bring back what Franklin Roosevelt labeled “this ancient atrocity.” Since then the movement has only advanced.

Child labor laws are among those most frequently flouted by businesses. The number of minors employed in violation of child labor laws in fiscal 2022 increased by 37.5% over the previous year, according to Department of Labor statistics. The number of minors employed in hazardous work in violation of state and federal laws increased by 26% in that period.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In the last fiscal year, the federal agency found 835 businesses violating child labor laws. Its fines and penalties averaged about $5,300 each. Do you think that’s stringent enough to dissuade would-be violators? Me neither.

What’s worse, “these numbers represent just a tiny fraction of violations, most of which go unreported and uninvestigated,” the labor-affiliated Economic Policy Institute observes.

If child labor laws already on the books can be flouted so easily, just imagine what will happen in states that have signaled that they don’t take their own laws seriously.

The prospect of carnage among child workers hasn’t put a dent in the campaign to make them more vulnerable to workplace injuries and death.

The rollbacks are often rationalized by conservative political leaders as promoting “parental rights.”

The moral scourge of child labor was supposedly eradicated in America more than 100 years ago. Red states are bringing it back in the name of parental rights.

That’s the argument voiced by spokespeople for Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders of Arkansas, who signed a law in March repealing a rule that required children under 16 to verify their age and obtain the written consent of a parent or guardian before obtaining a work certificate.

The Sanders administration defended the law by stating that “this permit was an arbitrary burden on parents to get permission from the government for their child to get a job.”

Another argument emphasizes the virtues of work for teens. On May 26, Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds of Iowa signed a pernicious law allowing 14- and 15-year-olds to work as many as six hours a day when schools are in session, to as late as 9 p.m. During school vacations, they could work as late as 11 p.m.

The measure also removes prohibitions against minors working in industrial laundries and in freezers and meat coolers.

“With this legislation Iowa joins 20 other states in providing tailored, common sense labor provisions that allow young adults to develop their skills in the workforce,” Reynolds said in signing the law. “In Iowa, we understand there is dignity in work.”

The Reynolds administration has been something of a one-stop shop for this kind hogwash that’s blind to the consequences of loosening child labor laws.

Last year, she signed a bill reducing the minimum age to 16 from 18 for workers providing child care for 3- and 2-year-olds without adult supervision. The law also raised the maximum number of toddlers that could be left under the care of adolescents without adult oversight — to seven 2-year-olds (up from six) or 10 3-year-olds (up from eight).

The new Iowa law also allows teens as young as 16 to serve alcohol in restaurants, as long as two adults are present and the young workers have been given “training on prevention and response to sexual harassment.”

Inflation is down sharply, employment is holding steady and GDP is growing. But Americans are still blaming Biden for a lousy recovery.

At least that provision recognizes some of the dangers in allowing teenagers to serve alcohol. Iowa has joined six other states in lowering the age for serving alcohol. Three more have such proposals in the legislative hopper.

What’s the big deal with allowing teens to serve alcohol? “Numerous studies have found that underage servers are more likely to sell alcohol to underage buyers,” reports Nina Mast of the Economic Policy Institute. “In general, greater access to alcohol is associated with higher rates of underage consumption. Permitting younger workers to serve alcohol will provide underage youth — both workers and customers — with increased proximity to direct and indirect alcohol-related harms that are especially acute for young people.”

Bars and restaurants where alcohol is served are already known for high rates of sexual harassment — these new laws will expose workers to these abuses at an age where their ability to fend them off is low, as is their access to legal redress. That’s not a concern for the promoters of the new laws and regulations, such as restaurant lobbyists, who drafted the new Iowa law.

The restaurant lobbyists had plenty of help from conservative and libertarian ideologues. Consider Jeffrey Tucker, who may be best known for promoting the egregious Great Barrington Declaration, a manifesto that discouraged vaccination and social distancing measures against the COVID-19 pandemic in favor of allowing the disease to virtually run rampant among Americans in the fruitless quest for “herd immunity.”

The declaration, which contributed to the toll of more than 1.1 million COVID deaths in the U.S., was embraced by politicians such as Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, who was desperate to establish his right-wing bona fides for a race for the presidency. His state has notched one of the worst death rates in the country from the disease.

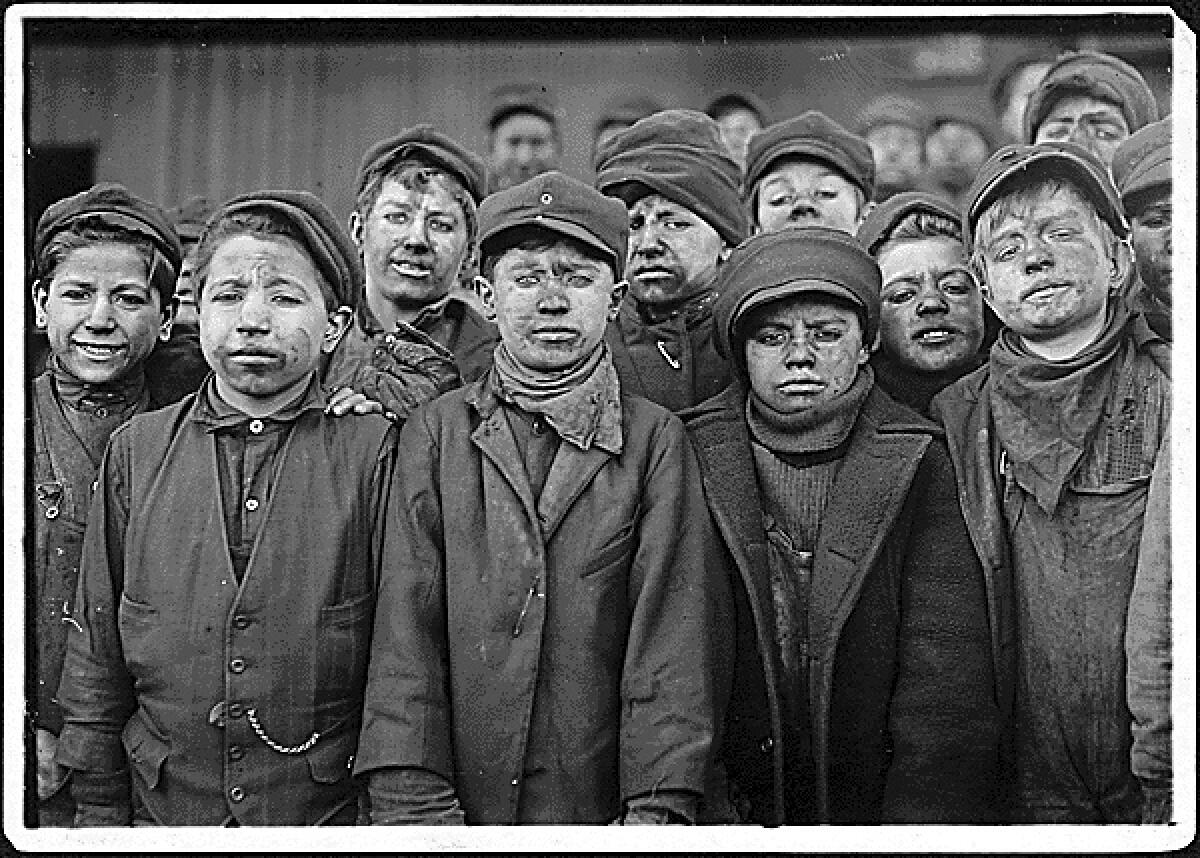

Tucker’s libertarian worldview glorifies child labor. In a 2016 article titled “Let the kids work,” Tucker ridiculed the Washington Post for publishing a gallery of work by the great photographer Lewis Hine of child laborers from 100 years ago, including miners and sweatshop workers as young as 10.

Tucker wrote that those children were “working in the adult world, surrounded by cool bustling things and new technology. They are on the streets, in the factories, in the mines, with adults and with peers, learning and doing. They are being valued for what they do, which is to say being valued as people.... Whatever else you want to say about this, it’s an exciting life.”

Strikes against Starbucks stores get all the publicity, but a mass strike by UPS workers could be the turning point for American labor.

What we want to say is: It’s a deadly life.

The only bulwark against the loosening of state child labor laws is federal law, which preempts state statutes that are less restrictive than the federal statute. The Department of Labor has already said that Iowa’s law violates the child labor provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, though it hasn’t yet taken legal action.

The federal provisions could be strengthened even more by ratification of the Child Labor Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment that was passed overwhelmingly by Congress in 1924. The measure was ratified by what was then a majority of 25 states by 1935; the total reached 28 by 1937, after which the movement stalled. (The first state to ratify the amendment, interestingly, was Arkansas; California was the second.)

The amendment makes explicit the right of Congress to “limit, regulate, and prohibit” labor by anyone under 18. It was a response to rulings by a conservative Supreme Court in 1918 and 1922 overturning federal child labor laws.

There’s no deadline for final ratification of the amendment, which needs 10 more states to sign on. Ratification has been rejected by 15 states, but that’s not binding. Those states include several currently under complete or partial Democratic Party leadership: Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina and Vermont. Five others never took a vote — New York, Rhode Island, Nebraska, Mississippi and Alabama. With a slight shift in the political winds, then, ratification could be within reach.

That could happen if more voters become aware of the scourge of child labor. Let’s hope that it doesn’t take any more deaths and injuries among child workers to bring reality home.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.