Column: Here’s how the billionaire owner of the Oakland A’s is planning to rip off two cities at once

Everyone loves a good heist yarn, so I suppose we should be grateful to Major League Baseball and a Northern California billionaire for providing us with one.

It’s the saga in which the Oakland A’s ballclub and its owner, an heir to the Gap fortune, are plotting to abandon the club’s home city and move to Las Vegas, enticed by more than $380 million in municipal subsidies for a $1.5-billion stadium and permanent immunity from property taxes.

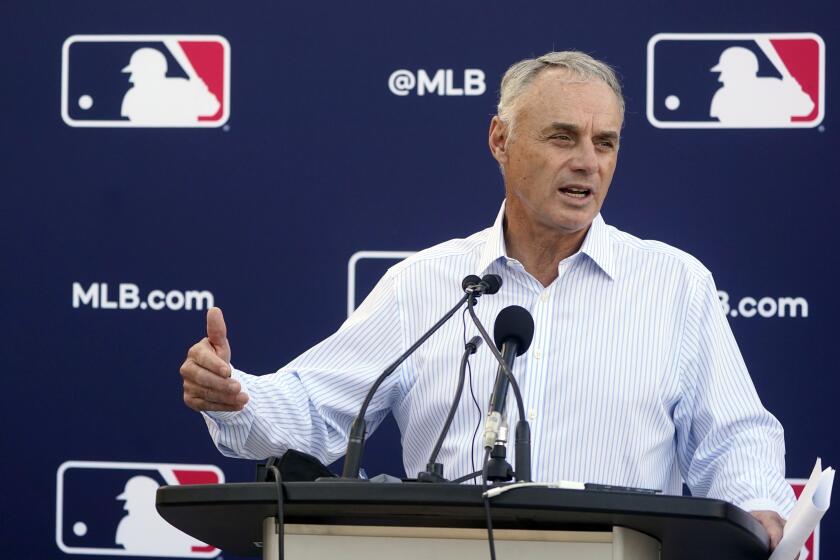

The move still requires approval by the owners of at least 23 of the league’s 30 teams. But it’s backed by MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, who has even offered to waive the customary relocation fee of $300 million if the deal gets done. So it should be an odds-on favorite over at the Vegas sports books.

It is great to see what is this year almost an average Major League Baseball crowd in the facility for one night.

— MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred insults fans of the cellar-dwelling Oakland A’s

The proposed deal has been bathed by its Nevada promoters in all the customary moonshine brewed to justify massive raids on the public purse.

The main argument always advanced for these subsidies is that they’re economic development boons. Sure enough, as my colleague Bill Shaikin reported, Ben Kieckhefer, chief of staff to Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo, told a legislative hearing in May that “the state general fund will make money on this deal.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Another ruse perpetrated by stadium promoters is to conceal the size of the public handout. At the same hearing, Kieckhefer declared that the public financing package for the stadium “contains no new taxes imposed against the residents of Nevada or our guests.”

The deal requires the floating of $120 million in bonds by Clark County and $180 million in tax credits. No new taxes, sure — unless the county or state needs a way to cover the public services that would otherwise be funded by those bonds and taxes.

As for the economic development gains, they’re unlikely to the point of being sheer fantasy. For more than 30 years, just about the most consistent finding in all economic research has been that stadium projects almost always “fall well short of covering public outlays,” a team of economists concluded last year. “Thus, the large subsidies commonly devoted to constructing professional sports venues are not justified as worthwhile public investments.”

The craze for public financing of stadiums for team owners who could often pay for construction out of their own pockets peaked in the 1990s, when public entities floated billions in tax-exempt municipal bonds, raised sales taxes and even dipped into their general funds to finance what were essentially business venues for multibillion-dollar private enterprises. Of 59 projects then underway in the U.S., I reported in 1997, all but five were wholly or partly funded by taxpayers.

The trend faded after that but never entirely disappeared. Recently, it has been showing new life. Last year, the New York state Legislature approved a subsidy of at least $850 million in state and local funds — and possibly more than $1 billion, when all the giveaways are factored in — for a new stadium for the NFL‘s Buffalo Bills. The team’s owner, oil and gas magnate Terry Pegula, has a net worth of $6.7 billion, according to Forbes.

The National Hockey League joins the club of powerful organizations letting themselves get bullied by Ron DeSantis.

The Bills deal was derided by sports economist Victor Matheson as “one of the worst stadium deals in recent memory — a remarkable feat considering the high bar set by other misguided state and local governments across the country.”

The deal narrowly edged out the $750-million subsidy Nevada provided for the former Oakland Raiders of the NFL in 2022 as the largest such handout in history. The money will come partly from the Las Vegas hotel tax, which otherwise pays for public services.

As for claims that stadium projects produce jobs, that’s also nonsense. One hired gun pushing the A’s stadium deal in Las Vegas told Shaikin that the ballpark would produce 5,400 jobs a year in team and stadium operations.

That’s an absurdly misleading number. History teaches us the truth about stadium jobs: There may be thousands of them on game day, but those are mostly low-wage cooks, janitors, security guards, parking attendants and ticket-takers. The higher-wage jobs generated by construction are only short-term.

At Levi’s Stadium, the Santa Clara home of the San Francisco 49ers, for instance, game-day employment comes to about 4,500 workers, but permanent stadium jobs in departments such as marketing and sales number only about 60.

One should not overlook all the hidden subsidies that typically fill the pockets of sports owners with new stadiums, even those claiming to be entirely privately funded.

The pitch for what became SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, home of the NFL Rams, claimed that no public money would be spent. But the fine print revealed that the city would eventually have to reimburse the team for services such as game-day fan shuttles and police and fire protection, none of which would be necessary except for the stadium.

Who will stand up for the poor plutocrats who own Major League Baseball?

The subsidy demanded from Las Vegas by Major League Baseball and A’s owner John Fisher, whose parents founded The Gap and who has a net worth estimated at $2.2 billion, would be contemptible enough. But it’s made only worse by Fisher’s behavior as owner.

Fisher acquired a stake in the A’s in 2005 and became sole owner in 2016. Since then, he has systematically dismantled the team and allowed the stadium to fall apart, while he and Commissioner Manfred wept crocodile tears over the lack of fan support.

Fisher launched ostensibly serious proposals to move the A’s out of the Oakland Coliseum and into new quarters in San Jose or other nearby communities. Oakland municipal officials trying to work with him on a plan to keep the team accused him of sabotaging those efforts, in part by insisting on massive subsidies for expansive joint stadium/commercial/residential developments.

After the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, when the A’s won the American League’s West Division, Fisher proceeded to trade or sell off the team’s best and most popular players. The player payroll went from $92 million in 2019 (sixth worst in the league) to $32.5 million last year, dead last.

The Coliseum, which was opened in 1966 during a misbegotten trend for multipurpose sports venues — those that could accommodate football gridirons and baseball fields — was never an inviting place to watch a baseball game, in part because the seats were so distant from the action that they seemed to be in a different ZIP Code.

Six decades later, it was well past its natural life span. During one game, it flooded with sewage. On another occasion, the lights went out. Feral wildlife roamed the increasingly vacant corridors. Then, for the 2022 season, Fisher doubled season ticket prices.

This year, attendance has averaged about 10,000 fans per game; the Dodgers pull in nearly five times as many and the Angels three times as many. At the May 15 game between the A’s and the Arizona Diamondbacks, only 2,064 seats were occupied, the lowest attendance for an A’s game in 44 years.

Column: A stunning tax ruling favoring the 49ers reminds us of the folly of public football stadiums

The question of whether publicly financed football stadiums are a boon or a bust for their local communities has been debated for years, with learned opinion tending toward the latter.

Why should anyone at all turn out? The A’s have lost nearly three out of every four games so far this season. They’re last in the division, 26 1/2 games out of first place. As of this writing, they have the worst record in baseball.

Yet these fans can be a hardy bunch. On June 13, while the Las Vegas subsidy deal was being voted on by the Nevada Senate, the fans staged a “reverse boycott,” in which 27,759 spectators saw the team beat the Tampa Bay Rays.

Manfred responded to the turnout with the disdain of someone who doesn’t care about the quality of baseball in his league. “It is great to see what is this year almost an average Major League Baseball crowd in the facility for one night,” he sneered.

That’s been the theme of this disgusting saga: Fisher and Manfred blaming the fans and the city for their own failings — in fact, for what look like deliberate efforts to destroy the viability of a major league sports team to justify moving it to a new city.

Las Vegas civic leaders may be crowing about attracting another sports team to their town, to join the Raiders and the Golden Knights, a National Hockey League expansion team.

But they should start worrying now. If Major League Baseball and the NFL can screw over Oakland, which supported its teams for decades, the day may come when Vegas discovers that the leagues don’t care about its fans, either.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.