Column: The rich men who control baseball show they don’t care about fans, again

It’s easy to say that in labor negotiations each side must give a little. That won’t do in the case of Major League Baseball.

The millionaires and billionaires who control the league faced a stark deadline to reach a deal with the baseball players to avoid canceling the start of the 2022 season, and blew right past it.

As we write, there’s no indication of when contract talks may resume in earnest or how much of the coming season will be lost.

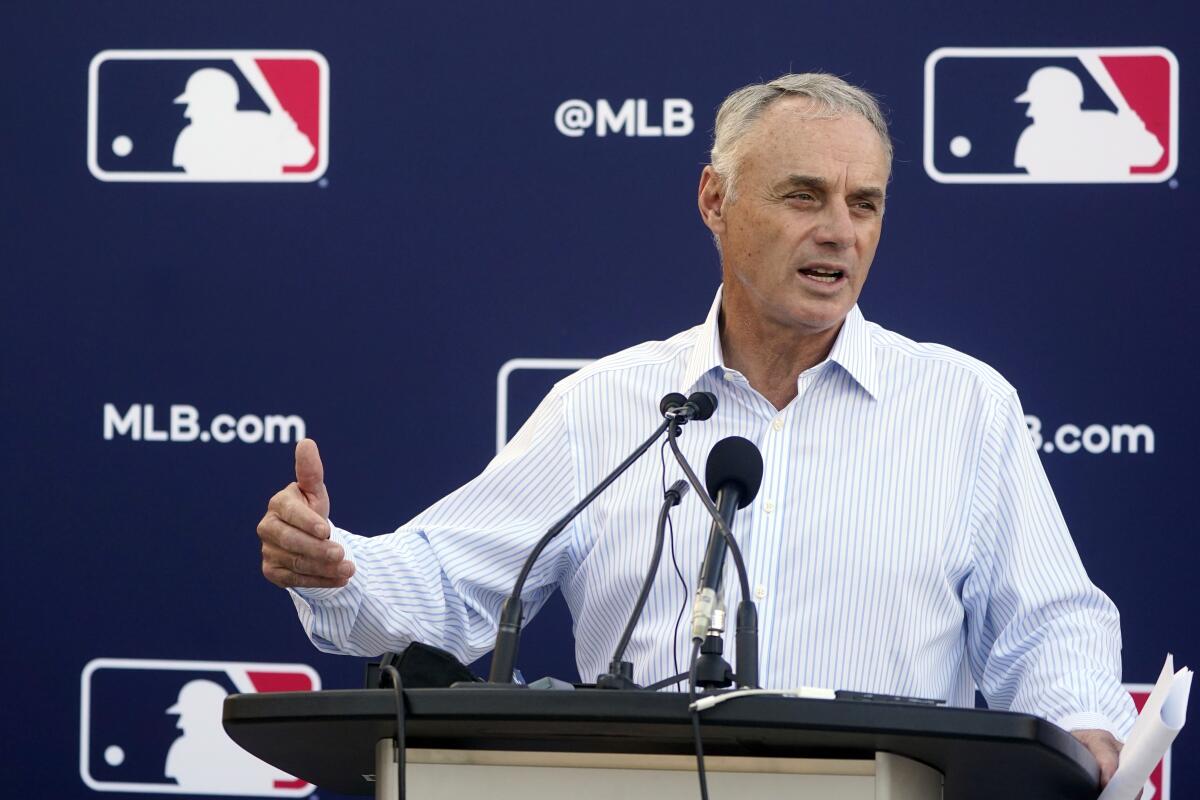

I had hoped against hope that I would not have to be in the position of canceling games.

— MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred

It should not be forgotten that the owners fired the first shot in this battle by imposing a lockout on Dec. 2, when the previous player contract expired. Commissioner Rob Manfred called the step a “defensive lockout,” but it’s more accurate to view this as an owners’ strike. The owners then waited 43 days to make an opening contract offer.

The lockout was entirely unnecessary. Spring training and the season could have proceeded under the existing contract while the two sides continued to talk.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

When talks broke off on Tuesday, the owners were proposing to raise the minimum salary for players to $675,000 this year from the current $570,500, with increases of $10,000 a year.

That’s less than 1.5% a year, when even 2% is considered low inflation. The union proposed an increase to $725,000 this year, $20,000 raises in 2023 and 2024, and inflation-indexed raises after that.

Another major sticking point is the luxury tax, which is the league’s instrument for discouraging teams from paying players more. The owners sought to raise the tax threshold to $220 million from the current $210 million in each of the next three seasons, and to $230 million by 2026.

My colleagues Bill Plaschke, Bill Shaikin and Meg James are reporting that for the second year in a row, Los Angeles Dodger games may be blacked out for TV viewers in Southern California, except for subscribers to Time Warner Cable.

The MLB Players Assn. wanted it raised to $238 million this year and by steps to $263 million in 2026. Only two teams paid the luxury tax for 2021 — the Dodgers, who were assessed $32.65 million, and the San Diego Padres, who were charged $1.2 million.

The players were willing to give on some demands by the owners, including an expansion of the playoffs (the owners wanted to expand postseason eligibility to 14 teams from 10, the players were willing to go to 12), and advertising on uniforms. But they ran up against an immutable law: Plutocrats are never satisfied with what they have when they think they can get more.

“I had hoped against hope that I would not have to be in the position of canceling games,” Manfred said in a written statement Tuesday. “We worked hard to avoid an outcome that is bad for our fans, bad for our players and bad for our clubs.”

It’s clear he didn’t work hard enough, and the owners didn’t care enough.

In that vein, it’s proper to consider who the owners are. As my colleague Mike DiGiovanna compiled the statistics from sources including Forbes and other potentate trackers, even the most poverty-stricken owners have net worths in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

On the bottom rung is Robert H. Castellini, a fruit-and-vegetable wholesaling heir who owns the Cincinnati Reds. His net worth is a mere $400 million, but like his fellow owners he’s done well by his team, which he bought in 2006 for $270 million; it’s worth an estimated $1.08 billion today.

At the top of the ladder is Steve Cohen, owner of the New York Mets, whose $14.6-billion fortune derives from his hedge fund. Between them are owners whose fortunes are based on banking, telecommunications, cable television, energy and commodities trading, real estate and meatpacking.

There’s an heir to a newspaper fortune (Bob Nutting, owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates), an heir to the Gap (John Fisher, owner of the Oakland A’s) and the owners of the Little Caesar pizza chain (the Illitch family, owners of the Detroit Tigers). Arte Moreno, owner of the Angels, made his money — an estimated $3.3 billion — in billboard advertising. Mark Walter, chairman of the Dodgers, is CEO of Guggenheim Partners, an investment firm that bought the team in 2012.

New analyses show that cheating didn’t help the Astros, and may have hurt their record

The internal finances of MLB teams are closely held except for one — the Atlanta Braves, which are owned by the public company Liberty Media and therefore disclose their numbers publicly. In 2021, according to Liberty’s public filings, the team turned an operating profit of $111 million on revenue of $568 million, a healthy profit margin of almost 20%.

More to the point, owning a professional sports team is essentially a capital-gains play rather than a hunt for annual profits. By that measure, every owner has done well except perhaps for one — Bruce Sherman, owner of the Florida Marlins. The value of that team has declined to about $990 million from the $1.2 billion he paid in 2017, possibly because of Sherman’s poor management.

Just the other day, Sherman lost his partner Derek Jeter, the former Yankees star, who quit as CEO reportedly because he felt he was getting stiffed on Sherman’s promise to invest in the team.

Manfred has poor-mouthed the experience of team ownership, asserting that most owners could have done better by investing in the stock market. He was immediately called out by Travis Sawchuk, who follows team economics at the Score and who calculated that since 2002, the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index has gained 308% and the value of MLB teams has climbed by 564%. In any case, even the poorest of the 30 owners can afford to take a capital gains hit here or there.

What’s often overlooked is that owners of major league sports teams acquire the opportunity to dip their hands directly into taxpayers’ pockets. Even purportedly privately financed sports stadiums generally require infrastructure improvements such as highway widening or mass-transit upgrades, paid for by the public. They’re sold to voters as economic development projects but almost never deliver.

Publicly financed venues are almost always a drain on public budgets. Oakland, to take one example, is facing a bill of more than $1 billion, to be partially financed through a public bond issue, for infrastructure improvements for a proposed bayside site for an A’s stadium.

The hilariously named Guaranteed Rate Field, home of the Chicago White Sox, was built with $137 million in financing from the state of Illinois. (The naming rights belong to a mortgage lender.) Great American Ball Park, home of the Reds, was financed with a 1/2% sales tax increase on local voters. The Reds pay $1 a year in rent.

Renovation plans for the Arizona Diamondbacks’ Chase Field embroiled the team and Maricopa County in a lawsuit over the D-backs’ demand that the county pay for an estimated $185 million in needed renovations.

Despite these benefits for owners, the mismatch between team revenues and player payrolls is stark. MLB experienced its 17th consecutive year of revenue growth in 2019, the last pre-pandemic year, when gross revenue hit $10.7 billion, up from $10.3 billion the year before.

In 1992, when Bud Selig became full-time commissioner, total revenue was $1.2 billion. That would be about $2.4 billion in today’s dollars. in other words, the take for MLB owners has increased five-fold in that time.

Despite the steady run-up in revenue, opening day payrolls have done worse than stagnated. They averaged about $132 million per team in 2021, according to Spotrac. That’s a decline from the peak of about $141 million in 2017.

The truth is that for all the PR the teams put out about their love for the fans, the fans often come last in their hearts, well after the quest for lucre.

Dodger fans don’t need a very long memory to find gold-plated evidence of how little the owners care about the fans. Starting in 2014, Dodger games were blacked out on television across most of the Southland because its new owners, led by Guggenheim Partners, reached a 25-year deal with Time Warner Cable worth $8.35 billion.

The cable company then tried to get its money back by hawking the games to the other pay-TV outlets in the region at premium prices. The other local outlets refused to pay, as did the satellite providers DirecTV and Dish. So 70% of the local fans — those outside the Time Warner subscription zone, lost their access to games.

As I wrote at the time, this was a case of the magic of the free market getting trumped by the black magic of greed. The Dodgers held out for the highest price they could get for the TV rights. Time Warner figured it could mulct the other pay-TV companies for every last dime because, really, what TV service would dare not carry the Dodgers, whatever the price? The answer was, all of them.

Dodger games didn’t come fully back to local TV until 2020 — just in time for the pandemic-shortened season.

The lockout and game cancellations resulting from the current labor standoff are merely another indicator of how much the owners really care. Major League Baseball could have kept to its spring training and season schedules if it wished, operating by the provisions of the expired collective bargaining agreement while they continued to talk with the players association.

Instead, they’ve chosen to play hardball with the players. The fans, however, can be forgiven if they see the pitch thrown at them as beanballs.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.