Column: Don’t blame the IRS for its lousy service. Blame Congress

With tax season already underway — the filing deadline this year is April 18 — complaints about the Internal Revenue Service are already rolling in.

We’re not referring to complaints about taxes in general — those are always with us, after all — but complaints about the agency’s customer services. Issues such as how long it takes to answer the phone, process returns and refunds and so on.

Those tend to peak as tax day bulks large on the horizon. This year is no exception. The complaints are most vociferously sounded on the right — two recent examples come from National Review and the Cato Institute.

This looks like the tax system of a plutocracy.

— Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, UC Berkeley

Blogger Kevin Drum rightfully condemns their grousing as manifestations of “brass,” for reasons we’ll cover in a moment. But they’re felt by any taxpayer who, for one reason or another, needs to speak personally with an IRS representative.

Things got worse during the pandemic: One member of my immediate family didn’t receive his 2019 refund until the summer of 2021, for instance.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But those who suggest that the IRS is responsible for its own problems are blowing a thick cloud of smoke. That’s because finding the reason for the agency’s underperformance in customer terms requires looking elsewhere — specifically, on Capitol Hill.

Anti-tax conservatives in Congress have been systematically impoverishing the IRS for decades, with the unmistakable goal of undermining its ability to do its job, not to mention its public reputation.

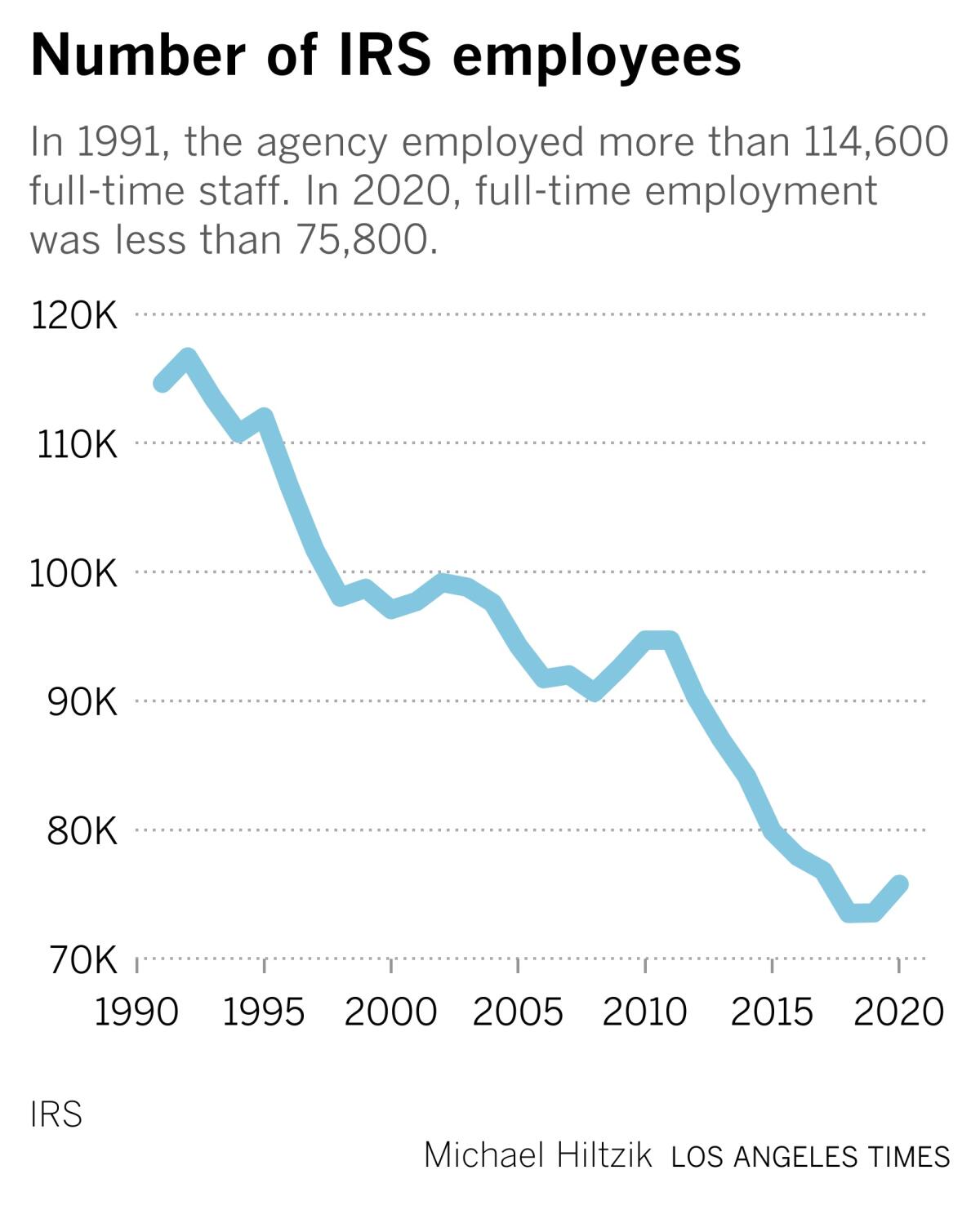

Here are the relevant statistics: In 1991, the agency employed more than 114,600 full-time staff to serve a population of 254 million and collect about $1.1 trillion in revenue. In 2020, according to the most recent IRS Fact Book, full-time employment was under 75,800, serving more than 330 million Americans and collecting $3.5 trillion.

Just over the last decade, the agency’s budget has declined by 20% in inflation-adjusted terms.

The right wing insists that somehow the IRS deserves less funding. That’s the point made by Dominic Pino of National Review: “The IRS is clearly a poorly run organization, and poorly run organizations should not be rewarded with more money,” he writes.

“If the agency actually improved its processes and better served taxpayers, its case for funding increases would weaken,” Pino writes, though how it improves its performance when it doesn’t get enough funding to do the job it has now, he doesn’t explain.

Pino draws his data from a screed by Chris Edwards, the tax policy chief at the Cato Institute. Both cite statistics published by the IRS National Taxpayer Advocate, which disclosed last year that only 11% of calls to the agency got answered.

That was “the worst it has ever been,” the advocate lamented. The advocate also reported that processing correspondence, which used to take about 45 days, now can take six months or longer.

As it happens, Edwards is marginally more charitable toward the IRS than Pino. He acknowledges, at least, that “the pandemic prompted the IRS to close or understaff numerous facilities in 2020,” and that “Congress has been passing huge and complicated tax breaks and subsidies for the IRS to administer.”

Each change, Edwards concedes, requires the IRS to create new tax forms, reprogram its computers, and take other steps that can “prompt millions of queries from confused taxpayers, which in turn consumes more IRS resources in response.”

It’s proper to examine the political environment in which the IRS operates. Put simply, it’s one that favors the rich. The highest-earning taxpayers have seen their tax rates and audit rates fall faster than everyone else over the years.

President Biden wants to step up the war on tax cheats, so of course the GOP and banks object.

According to a paper last year by John Guyton and Patrick Langetieg of the IRS and colleagues at UC Berkeley, Carnegie Mellon and the London School of Economics, IRS policies have fostered widespread tax evasion at the top of the income ladder.

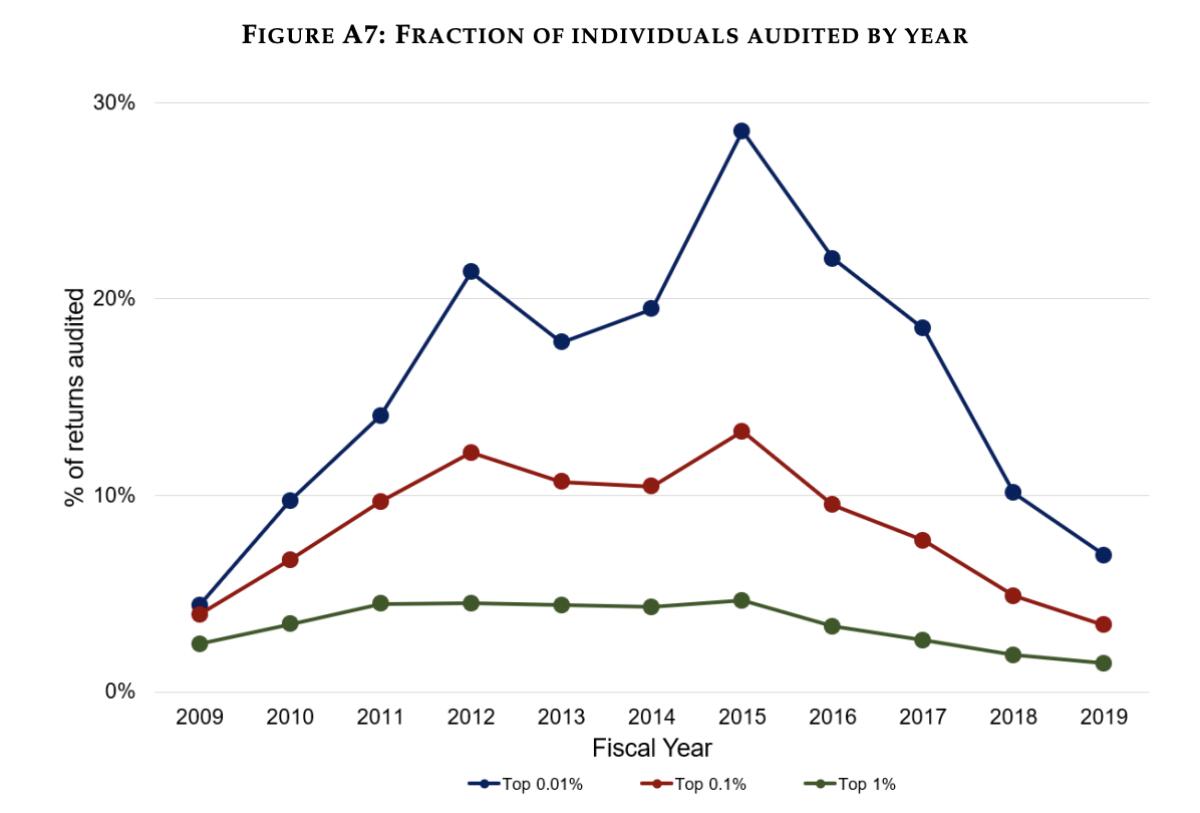

The share of audits performed each year of the top 1%, for example, fell from nearly 30% to less than 10% from 2015 through 2019.

As I reported in 2020, about 23,450 U.S. households reported income of $10 million or more in the 2018 tax year, averaging more than $26 million each in taxable income — the highest income bracket. Under the Trump administration, the IRS, according to its 2019 data book, audited seven of them. (Acknowledgements to journalist David Cay Johnston, who first ferreted out the statistic from IRS data.)

That audit rate of three-hundredths of one percent is about the chance of your being struck by lightning at some point in your lifetime. So it may not be surprising that wealthy taxpayers don’t think they have much to fear from IRS.

Trump may be out of office, but his approach to IRS enforcement is still being heard.

Last November, after President Biden proposed making an $80-billion investment in the IRS over a decade in part to upgrade collections efforts, David Kautter, a former acting IRS commissioner under Trump, snarked that the funding was “dramatically in excess of what the IRS needs and could probably effectively use.”

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?

The agency’s enforcement indulgence for the wealthy comes on top of the gains the same people have scored in their tax rates, also thanks mainly to Republican initiatives.

From 1960 through 2018, according to calculations by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of UC Berkeley, the total wealth of the bottom 50% of U.S. income earners rose by about 1.5 times, from an average $3,500 to $5,200 (in 2018 dollars) and their average tax rate rose from 22.55% to 24.2%.

Wealthy Americans know the capital gains tax is their biggest loophole — and they won’t give it up easily.

The wealth of the 400 richest Americans, however, rose by more than 24 times, from an average $276 million to an average $6.7 billion (also all in 2018 dollars), while their average tax rate declined from 54.4% to 23%.

“This looks like the tax system of a plutocracy,” Saez and Zucman wrote in their 2019 book, “The Triumph of Injustice.”

With tax rates at the top barely exceeding 20%, they observed, “wealth will keep accumulating with hardly any barrier. And with that, so too will the power of the wealthy accumulate, including their ability to shape policymaking and government for their own benefit.”

The effect they identified could be seen during the course of the great IRS “scandal” of 2012 and 2013, ginned up by GOP functionaries such as then-Rep. Darrell Issa, (R-Vista) (then identified as the richest member of Congress).

Issa claimed that the agency had targeted conservative tax-exempt nonprofits for scrutiny over whether they were actually political fronts, which would be illegal. His purported investigation succeeded in intimidating the IRS from doing its job, which allowed “social welfare” nonprofits — C4 groups in formal parlance—which are supposed to be primarily devoted to social issues, not politics — to keep funneling illicit contributions to politicians.

The IRS traditionally has used C4 designations to cover religious groups; cultural, educational and veterans organizations; homeowners associations; volunteer fire departments; and the like. In recent years, however, overtly political groups began to claim C4 status, which allowed them to keep their donor lists secret and to avoid paying taxes on certain income.

In the end, it turned out that the purported scandal was a myth. An exhaustive study by the Center for Public Integrity identified only 10 C4s whose applications for tax-exempt status had been rejected by the IRS since 2010. Among them were seven Democratic-affiliated organizations.

But those inquiries were the last of their kind. After Issa’s investigation, “the IRS’ nonprofit division ... effectively lost whatever nerve it had left,” the center reported. Among the beneficiaries of its paralysis was what was then the biggest “social welfare” front, Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS.

One might be tempted to say, “mission accomplished.” Unfortunately, however, the mission of hobbling the IRS is never complete in the eyes of its enemies in Washington.

So if you become irritated at the IRS’s unresponsiveness to your workaday inquires, you should remember that its shortcomings are caused by the actions of lawmakers. Thanks to them, the agency is equipped to be responsive to a certain class of taxpayers — rich ones.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.