Column: Lose your health coverage? Don’t hesitate to haggle with medical providers

How dumb is it to tie people’s health insurance to their jobs? Just ask Steve Pelletier.

The Camarillo resident worked for a Los Angeles tech startup that, like most companies providing full-time employment, offered health coverage as an employment benefit.

“Basically the company started running out of money last fall,” Pelletier, 60, told me. “We stopped getting paid salaries but they kept our health coverage going.”

For a while.

“I went to a couple of recent doctor appointments,” Pelletier said. “One of the doctor’s offices told me my insurance had been canceled. That’s how I found out.”

And just like that, he was on the hook for more than $8,000 in inflated medical bills.

These included about $1,200 billed by his Westlake Village doctor for a routine physical, $1,800 for blood work related to the physical, and around $5,300 for a throat specialist at UCLA treating what Pelletier called “messed up vocal chords.”

He contacted his doctor and UCLA to explain the situation. Both responded by offering discounts for treatment provided.

The one holdout: Quest Diagnostics, which wanted the full $1,800 for Pelletier’s lab tests.

“I spoke with a number of people at Quest,” he said. “They told me it’s not their policy to negotiate prices.”

A new survey finds that consumers are fed up with endless telephone wait times and glitchy automated menus. Why aren’t companies listening?

This is another example of the in-it-for-the-money nature of the $4-trillion U.S. healthcare system — an approach that all too often places profits ahead of patients.

It also yet again illustrates the ridiculousness of linking health coverage to people’s jobs. Lose your job, lose your health insurance.

Is it any wonder a 2019 study found that medical bills were a primary factor in about two-thirds of personal bankruptcy filings? More than half a million U.S. families go bankrupt annually because they can’t afford healthcare.

A key problem here is doctors and hospitals routinely billing insurers insane sums to nudge reimbursement rates higher.

List prices for healthcare, known as the “chargemaster,” are usually orders of magnitude higher than actual treatment costs or the amount providers will settle for from insurers.

A 2016 study found that most hospital chargemaster prices are four times greater than the actual cost of providing treatment.

Some healthcare services, such as CT scans, were billed at levels nearly 30 times higher than the true cost, the study found.

The researchers concluded that there’s no reason for this other than to boost profits. “Markups are being used to maximize revenue,” they said.

In the first half of the year, HCA Healthcare, the country’s largest hospital company and the industry bellwether for earnings, reported nearly $3 billion in profit.

UnitedHealth Group, parent of UnitedHealthcare, the country’s largest private health insurer, took in more than $9 billion in profit during the first half of the year.

UnitedHealthcare wants to deny coverage for emergency care it deems unnecessary. It’s also placing new limits on out-of-network treatment.

Outlandish chargemaster pricing isn’t just an accounting gimmick. It has very real ramifications for patients, especially those who fall between coverage cracks.

“Uninsured and out-of-network privately insured patients are generally billed the chargemaster price, unless the hospital offers them a discount,” the 2016 study found.

That’s the trap Pelletier found himself in. Without his employer-provided coverage, both his doctors initially said he had to pay the chargemaster rate for treatment.

“I told them this wasn’t fair,” Pelletier said. “I offered to pay the same amount they would have been reimbursed by my former insurer,” Anthem Blue Cross.

His general practitioner found this reasonable, reducing Pelletier’s bill from the chargemaster rate of $1,200 to what would have been the insured reimbursement rate of about $400.

UCLA tried to play a little rougher. Pelletier said the hospital offered to reduce his bill by 30%, making him responsible for a payment of about $3,500.

He countered that he knew from prior visits to the throat specialist that the insured reimbursement rate is closer to $2,200. Pelletier offered to pay that amount. UCLA agreed to this lower (but still high) sum.

Quest, however, wouldn’t budge. Until I knocked at their door.

Following his son’s treatment, a Santa Monica man was left to wonder what exactly he was paying for after a nearly $32,000 hospital bill arrived.

A couple of days after I contacted the company about its talk-to-the-hand approach to billing, Pelletier said he received a call from Quest saying his $1,800 bill was being slashed by two-thirds to around $600.

Jennifer Petrella, a company spokesperson, declined to comment on Pelletier’s situation.

“We encourage individuals to check their benefits with their insurance provider prior to going to the lab for testing,” she told me. “Additionally, Quest Diagnostics has several avenues to help patients that are uninsured or underinsured, such as our Uninsured Patient Program and Patient Financial Assistance Program.”

Pelletier said he was presented with these options but found them unsatisfactory. He noted that past Quest bills showed the company received just $180 from his insurer — a small fraction of the chargemaster rate.

If you find yourself in a similar situation, the first step is to contact your medical provider and see what flexibility may be available. Most doctors and hospitals will offer discounts to the uninsured, usually in the 30% range.

Don’t hesitate to do what Pelletier did. If you lose your coverage but know from past bills how much your insurer would have paid, offer that amount. Many providers will see this as acceptable, at least on a one-time basis.

If these steps don’t produce satisfactory results, it may be time to bring in a hired gun — a professional patient advocate. These are people who know the ins and outs of the healthcare system and can help facilitate an equitable payment solution.

“When a person is trying to handle this themselves, they generally reach out to providers with an emotional plea,” said Prissi Cohen, a registered nurse and patient advocate in L.A.

“This is business,” she told me. “You have to make it about business.”

Never agree to pay the chargemaster rate, said Martine Brousse, a Culver City patient advocate and mediator. “The chargemaster means nothing,” she said.

Rather, Brousse advised going directly to a doctor or nurse you’re familiar with, someone who can ask the billing department to cut you a break.

If you’re still getting nowhere, and you’re facing an unusually large medical bill, that’s when a patient advocate can really help. But their services don’t come cheap, often running $100 to $500 an hour.

A good place to start: AdvoConnection, an online directory of patient advocates that allows you to search in your area.

But these are all Band-Aids. The real solution is to transform our healthcare system into one closer to those of other developed countries.

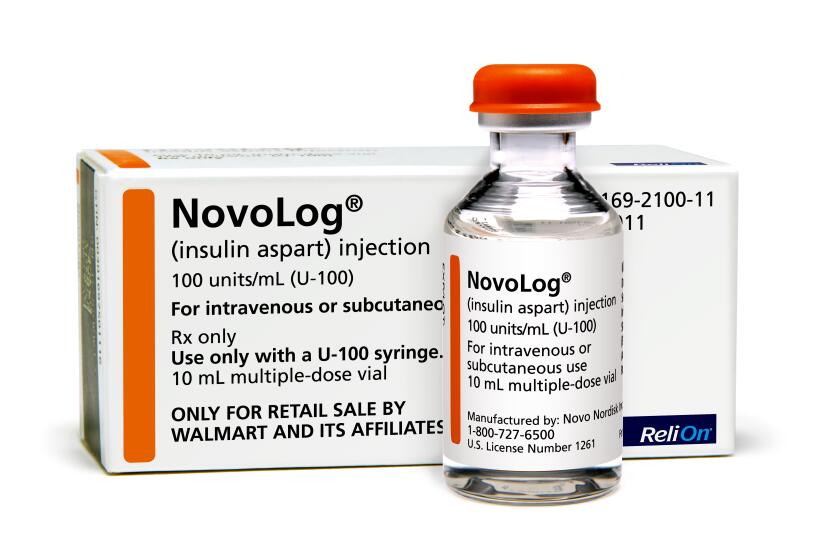

Walmart has unveiled a private-label insulin that sells for about a fifth of what similar insulins cost. Can we expect the same for other drugs?

By that I mean systems under which everyone is covered, healthcare costs are about half what Americans now pay, and the emphasis is on making people well, not on making money.

An added benefit of a national insurance system — “Medicare for all,” say — is that it would eliminate employment from the equation. No longer would you need to worry about having a job to go see the doctor.

The two would be, and should be, separate matters. That’s how most of our economic peers abroad do it. It’s the most sensible and humane way to provide coverage.

Or we could just stick with employer-based health insurance and chargemaster prices.

Because, you know, they’ve worked so well for patients.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.