Column: Trump will get millions in post-presidential benefits, thanks to Harry Truman’s lies

Part of the fallout from the violent and seditious end of the Trump administration concerns whether Donald Trump should receive the lavish government benefits showered on our other ex-presidents.

The question was raised with particular force during the impeachment proceedings following the Jan. 6 insurrection.

The discussion then focused on whether Trump’s conviction at a Senate trial, as unlikely as that was, would cancel his benefits. Indeed, one rationale for the second impeachment was to take Trump off the government rolls.

The fact of the matter is that when he left the White House, Truman was loaded....He was Rich with a capital ‘R,’ and way into the 1%.

— Paul Campos, University of Colorado Boulder

Legal experts concluded, however, that his post-presidential benefits could be revoked only if he were removed while still in office.

The article of impeachment wasn’t even submitted to the Senate until Jan. 25, after Joe Biden, Trump’s successor, had already been sworn in, and Trump was subsequently acquitted anyway. So his benefits appear to be safe.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But the discussion pointed to another question: How did ex-presidents end up in line for post-presidential largess in the first place?

The answer brings us back to the 1950s and a string of lies Harry Truman told about his own financial situation.

Truman let it be known that he had entered presidential retirement in 1953 on the verge of destitution. His pitch resulted in the enactment of the Former Presidents Act in 1958, which endows this elite cadre with lifetime benefits.

The truth about Truman, however, is somewhat different. Completely different.

“The fact of the matter is that when he left the White House, Truman was loaded,” says Paul Campos, a law professor at the University of Colorado Boulder who has done what no Truman historians seem to have bothered to do — examine the financial records in the Truman archives in Independence, Mo. “He wasn’t just comfortably well off. He was Rich with a capital ‘R,’ and way into the 1%.”

It gets worse, as Campos has related at Lawyers, Guns & Money, an indispensable group blog where he’s a contributor, and in a July 24 piece in New York Magazine.

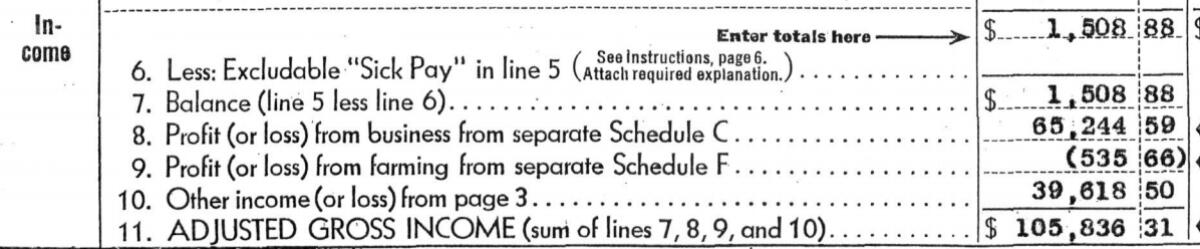

Campos reports that Truman accumulated a chunk of his wealth by apparently misappropriating large sums from the U.S. government, in the form of an annual $50,000 nonaccountable and nontaxable expense account provided by Congress for the first two years of his elected term (1949-1953). At the time, income over $100,000 was taxed at a rate of about 90%, making the untaxed funds vastly more valuable for Truman.

In a new ranking by historians, Donald Trump only ranks fourth as worst U.S. president ever. How can that be?

Even though Truman didn’t have to formally document the account’s usage, it wasn’t designed as a personal slush fund. But that’s how Truman used it. In a 1953 draft will that Campos found in the archives, Truman advised his wife, Bess, of a hoard of cash in a safe deposit box. “It came out of the $50,000 expense account that was not accountable for taxes,” he wrote. “It should be put into bonds except what you need for immediate use.”

After the first two years, Congress made the expense account taxable if used for personal purposes.

The truth about Truman’s finances should lead to a new reconsideration of the Former Presidents Act, which hasn’t lacked for controversy even before this. A bipartisan measure paring back the benefits passed both houses of Congress in 2016 but was vetoed by Barack Obama, who asserted that it would interfere with contractual arrangements already made by living former presidents.

The FPA’s benefits aren’t modest. They include an inflation-indexed annual pension keyed to the stipends of ex-Cabinet secretaries ($221,400 this year); office space anywhere in the U.S. and staff compensation up to $150,000 a year; up to $1 million a year in security and travel reimbursements, plus another $500,000 for former first ladies; lifetime Secret Service protection; and health coverage for ex-presidents who accumulated at least five years in the federal employee health insurance system (so Trump and Jimmy Carter, who didn’t meet the five-year threshold, are ineligible).

According to the right-leaning National Taxpayers Union Foundation, which advocates canceling most of these perks for all ex-presidents, the government has been spending about $4 million a year on our four living ex-presidents, not including Trump.

The smallest amount, about $480,000, has been budgeted in fiscal 2021 for Jimmy Carter, who tends to live modestly; Clinton, George W. Bush and Obama are all budgeted at more than $1.1 million. But all are multi-millionaires and capable of garnering handsome incomes through writing, speaking, serving on corporate boards and other projects offered to your average ex-president.

Truman’s ostensible modesty in his presidential retirement is commonly used as a reproach to his money-grubbing successors. “Barack Obama is using his Presidency to cash in, but Harry Truman and Jimmy Carter refused,” was the headline on an article on this theme by Zaid Jilani in the Intercept.

Jilani quoted Truman, approvingly, as stating, “I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable, that would commercialize on the prestige and dignity of the office of the presidency.”

The same line shows up in a 2007 New York Times and Boston Globe op-ed by Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby, tweaking Bill Clinton for accepting lavish speaking fees and headlined, “Harry Truman’s obsolete integrity.” To his credit, after consulting Campos’ New York Magazine piece Jacoby published a mea culpa in the Globe, headlined “Harry Truman conned us all.”

Campos ascribes much of this canonization of Truman as a paragon of modesty to historian David McCullough, who in his 1992 biography etched into public consciousness the image of Harry and Bess Truman retiring to Independence, Mo., with no government support other than “other than his Army pension of $112.56 a month.”

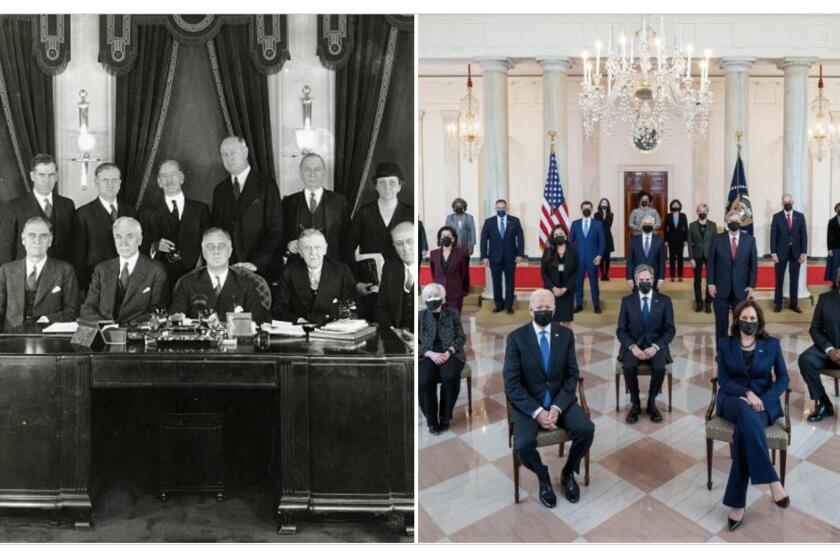

Biden is being compared to Franklin D. Roosevelt, but the resemblance is complicated.

But Truman had been pushing this narrative before leaving the White House, and more assiduously after his retirement. As Campos relates, in an interview with Edward R. Murrow (for which CBS apparently paid Truman $25,000), Truman complained that “the United States government turns its chief executives out to grass. They’re just allowed to starve.”

He asserted that only his inheritance of the family farm stood between him and penury: “If I hadn’t inherited some property that finally paid things through, I’d be on relief right now.”

As it happens, he hadn’t inherited the farm — it had been foreclosed on while he was a senator. He had bought it back, however, presumably on the expectation that the land would soar in value as suburbanization expanded, which is what happened.

Truman did enter public service without much money; when he was elected to the Senate in 1934 he was still paying off debts from a failed haberdashery business at home. But his compensation as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vice president and as president put him among America’s financial elite.

The presidential salary of $100,000, which Congress established in time for his elected term in 1949, would be worth $1.5 million today. In contemporary terms, it was lavish — as Campos observes, it matched the salary of Joe DiMaggio, then the highest-paid ballplayer in baseball.

That year, the median household income in America was $3,000. In comparison to today’s household median of $78,500, Truman’s salary would be worth about $2.6 million today.

In the draft will that Campos examined, dated 1953, Truman listed assets of $650,000. That comprised $250,000 in U.S. savings bonds, $150,000 in cash, $250,000 in land and a book contract he estimated to be worth $100,000. Adjusted for inflation, that would be worth about $6.6 million today. But as Campos calculates, the threshold for the top 1% of the earlier time was $125,000; today it’s $11.1 million.

Amazon’s campaign against a union drive in Alabama has drawn fire from President Biden.

“To be as rich today relative to other Americans as Truman was in 1953,” Campos writes, “a person would have to have a net worth of around $58 million.”

As for Truman’s circumspection in exploiting his post-presidency, he listed himself on his federal tax returns as “writer-lecturer-farmer.” The contract for his memoirs, which began reaching bookshelves in 1956, was $600,000 (more than $6 million in today’s terms). Truman groused to House Majority Leader John McCormack (D-Mass.) that although he had granted Dwight Eisenhower a tax break for Eisenhower’s wartime memoirs, Eisenhower didn’t return the favor after he became president.

Notwithstanding all this evidence found in Truman’s tax returns, which are available online, and the archival record, the image of Truman as a modest individual living without resources persists — not only in McCullough’s biography but others by academic historians.

His post-presidential privation is as central an element in the Truman identity as the presence of the sign reading “The Buck Stops Here” on his Oval Office desk. His biographers, not to mention the political commentators who cite him as a paragon of integrity, haven’t done their homework.

Campos suggests that one reason his true situation hasn’t been examined is the aura of steadfastness that surrounds him to this day — in the C-SPAN survey of historians recently published, he ranks sixth in esteem, after Lincoln, Washington, both Roosevelts and Eisenhower, despite a record of accomplishment that could fairly be judged as mediocre. But that’s hardly an excuse for the rosy coloration of his reputation.

It’s also true that some of Truman’s private financial disclosures weren’t available to researchers until the unsealing of Bess Truman’s papers in 2011. But the tax returns have been open for much longer, and “the tax returns basically blow the story out of the water all by themselves,” Campos told me.

As for why Truman so feverishly pursued more wealth despite his more than comfortable condition, Campos conjectures that he was haunted by a a gnawing sense of economic precariousness stemming from his business failures and a long pre-Washington life without money.

Even without the puncturing of the Truman myth, the time to revisit the Former Presidents Act is nigh. In today’s world, the pensions and subsidies awarded former presidents are just gravy on their healthy personal fortunes. Giving more money to Donald Trump, considering his own wealth and his post-presidential behavior, would be a scandal. But the scandal existed long before he came on the scene.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.