Column: In stunning upset, historians rule that Trump was not the worst president ever

Horseplayers know that you can never depend on a sure thing. But who could have expected that in a race to be deemed America’s worst president, Donald Trump wouldn’t only fail to win, but that he would come in only fourth?

Yet that’s the result of C-SPAN’s latest survey of presidential historians, released Wednesday, its fourth in a series that began in 2000 and is repeated every time there’s a change in administrations.

This year, Trump failed to beat out a triumvirate of slavery-era presidents who have occupied the three bottom rankings in every survey: Franklin Pierce, Andrew Johnson and James Buchanan.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That said, however, Trump has nothing to be proud of: He was judged worse than some of the outstanding zeros who have led the nation in the 232 years since George Washington’s inauguration in 1789.

Among them are William Henry Harrison, who served only 31 days in 1841 before succumbing to pneumonia; Warren Harding, whose administration set a standard for corruption that other occupants of the White House can only shoot for in vain; and Herbert Hoover, who is indelibly linked to the onset of the Great Depression.

The survey of historians is useful not only as grist for a multitude of barroom debates, but as a window into how the reputations of historical figures can shift with the tides of contemporary thought.

The voting panel has expanded from its original 58 members to 142 to reflect more diversity in age, gender, race and political philosophy; I’m a voting member by virtue of my published histories of the New Deal and the building of Hoover Dam.

Before delving deeper, a few words about methodology. The panelists were asked to rank presidents on a scale of 1 (“not effective”) to 10 (“very effective”) in each of 10 categories.

Those are public persuasion, crisis leadership, economic management, moral authority, international relations, administrative skills, vision or setting an agenda, relations with Congress, “pursued equal justice for all” and “performance within context of times.” The responses were averaged in each category and added together for a final score.

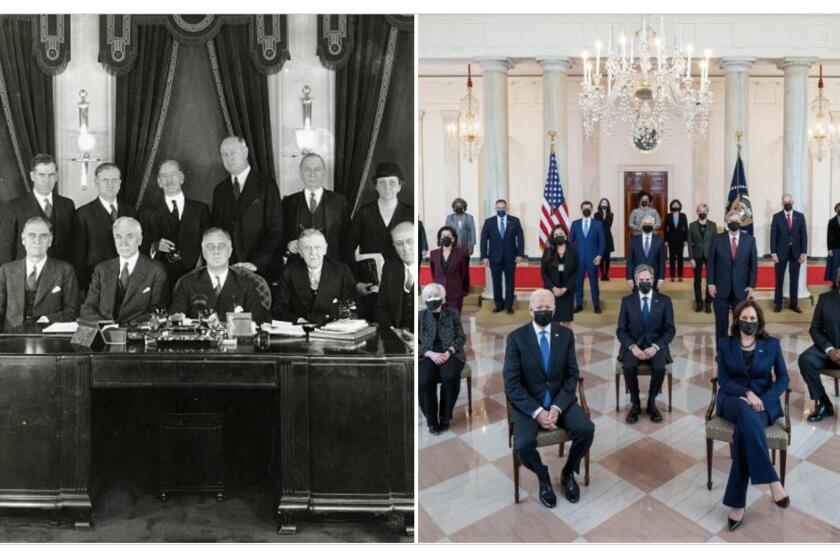

Few presidents are immune from reexamination. In this survey, stability appears to be the rule largely at the bottom and the top: Lincoln, Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt have had a lock on the top three slots every time — Lincoln has always ranked first, but FDR and Washington, who were ranked second and third respectively in 2000, swapped places in the 2009 poll and kept those rankings in 2017 and 2021.

Biden is being compared to Franklin D. Roosevelt, but the resemblance is complicated.

As for the three bottom-dwellers, their rankings testify to the enduring impact of the slavery era. Pierce, who served in 1853-1857, signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which launched a round of bloody conflict between pro-slavery and abolitionist forces, and oversaw enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, perhaps the most detested law in American history.

Pierce was followed by Buchanan, whose maladroit administration set the stage for the Civil War. Andrew Johnson, who succeeded the assassinated Lincoln, launched Reconstruction, one of the most profoundly mismanaged government projects ever.

Another pocket of consistency is the span of 35 years from FDR through Lyndon B. Johnson. The five presidents in that time frame have all landed within the top 11 in every survey.

“That tells me that’s seen by historians as a kind of golden age for the presidency,” says Richard Norton Smith, a biographer of Hoover, Washington and Gerald Ford who is one of the four advisors to the C-SPAN project, along with Douglas Brinkley of Rice University, Edna Greene Medford of Howard University and Amity Shlaes, a biographer of Calvin Coolidge and author of conservative histories of the Great Depression and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society program.

“Not surprisingly, that was an age of constant crisis, from the Depression, to the war, to the Cold War, to the civil rights movement in the ’60s,” Smith told me. “It’s also the age of mass media, whether radio or television.”

As laws allowing anti-transgender bias spread, a California response comes under attack.

But the reputations of many other presidents have experienced major shifts during the two decades of the survey. The biggest gain belongs to Ulysses S. Grant, whose ranking has risen from No. 33 to No. 20 over the course of four surveys; the biggest decline to Andrew Jackson, who has fallen from No. 13 to No. 22.

“You can explain all that through the prism of race,” Smith says. “The trend has been developing for years, but it has lately reached its maturity.” Grant’s image, formerly that of an individual in over his head among a platoon of corrupt relatives and camp followers, is now that of the last president until the late 20th century to send federal troops into the South to protect the interests of Black Americans.

By the same token, Jackson’s image as a “champion of frontier democracy,” as Smith puts it, has been revised with the recognition that his championship was chiefly enjoyed by white people. Now, he’s remembered as a holder of slaves and killer of Indigenous peoples.

A similar reconsideration has driven Wilson’s ranking down from No. 6 to No. 13. The drag on his reputation is visible in the category of “equal justice for all,” in which he has plummeted from No. 20 to No. 37.

Wilson used to be thought of as a beacon of Democratic Party progressivism — a model for the young FDR, who served him as an assistant secretary of the Navy — thanks to such achievements as the establishment of the eight-hour workday, the appointment of Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court, and the passage of the 19th Amendment legalizing women’s suffrage.

Henry A. Wallace, FDR’s vice president, foresaw the fascism of Trump.

Wilson is increasingly identified as an unremitting racist and segregationist, to the extent that Princeton University, where he served as a faculty member and as president from 1902 to 1910, last year took his name off its School of Public and International Affairs and from a residential college on campus.

That brings us back to Trump. Although he may have been outdone in general atrociousness by that slavery-era trio, the historians’ panel found little to recommend him. He’s ranked dead last on moral authority and administrative skills, and within four from the bottom on crisis leadership, international relations, relations with Congress, the pursuit of equal justice for all and performance within contemporary context.

Trump’s best showing is his ranking at No. 32 in public persuasion, but that points to a flaw in the survey’s construction. This category has almost no qualitative component.

It’s true that Trump was adept in his command of television and social media, but the important issue should be that he placed this skill at the service of a message of unalloyed racism, bigotry and mendacity. The first-place ranking in this category is held by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who used it to project moral authority, effective leadership in a series of crises, and a remaking of the federal government to serve the masses. Quite a difference.

In any case, as the survey shows that few presidential reputations are etched in stone, Trump’s record is bound to be reexamined with the passing of the years. It may not be a sure thing that it will decline, but if the administrations of Pierce, Buchanan and Andrew Johnson become more obscured by the mists of time, that’s probably a safe bet.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.