Column: The AMA throws a last-minute wrench into a plan to outlaw surprise medical billing

The persistent failure of Congress to ban surprise medical bills is one of those legislative mysteries that isn’t so mysterious once you follow the money.

In this case, the money comes from private equity firms that have been buying up emergency clinics, anesthesiology practices, air ambulances and other services that generate the bulk of surprise bills.

They’ve been fighting this legislation for years, sometimes hiding behind purported consumer advocacy groups that aren’t grass-roots, but astroturf.

The AMA has been against anything that might control costs, forever. So this is probably not surprising.

— Loren Adler, surprise billing expert

But there’s still a mysterious aspect to the continued fight to get a surprise-billing ban into federal law. It’s why the American Medical Assn. has tried to throw a monkey wrench into a last-minute bipartisan agreement that could result in the enactment of a ban before the end of this year.

In a letter sent Tuesday to the four congressional leaders, the AMA said it opposes the measure “because it would significantly disadvantage already stressed physician practices, particularly small physician practices.”

This is nonsense, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment. First, a quick primer about surprise billing.

One of the most dismal features of America’s fragmented and dysfunctional healthcare system, surprise billing happens when patients unknowingly receive treatment from a medical provider outside their health plan’s network.

Typically, the non-network providers can bill the patient any rate they choose; if they receive a reimbursement from the patient’s health plan, they can bill the patient for the balance.

Most commonly, this happens in two circumstances: when a patient is brought to a hospital for emergency care and doesn’t know that the emergency room staff or the ambulance service is out-of-network, and when a patient undergoes surgery and is unaware that the anesthesiologist, radiologist or other behind-the-scenes specialist is out-of-network.

There were a couple of endearingly all-American aspects to Tuesday’s announcement of a joint venture by Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway and Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase to reduce healthcare costs.

An emergency patient might not even be conscious when he or she is brought to the ER, and in a truly urgent case, may simply not be in a position to poll the staff about whether they’re in a health plan’s network.

When the bills for those providers arrive, they can come to thousands of dollars — surprise, surprise.

Not all out-of-network treatment produces a surprise bill. Some patients may deliberately choose to go to an out-of-network doctor, in which case they probably know they’re going to pay the price and have steeled themselves for higher bills.

“By and large, people just don’t choose out-of-network doctors when they have a choice,” Loren Adler, an expert on surprise billing at the USC-Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, told me.

Health plans are generally quite open about the consequences of going outside their networks. In-network doctors have negotiated their rates with the insurer in deals that give them lower reimbursements than the market might bear, but also brings them a larger patient base.

In return, they agree not to bill patients for more than the negotiated rate. Non-network doctors don’t face those restrictions.

Surprise billing consistently ranks high among the most detested features of American healthcare. Banning it has consistently won bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and in statehouses around the country.

California bars out-of-network providers at emergency rooms and by non-network doctors at in-network hospitals, rules followed by 16 other states. Less comprehensive protections are in place in 17 other states; 18 don’t provide any protections at all.

Biden doesn’t need a Democratic Senate to save American healthcare reform.

But even those states with the most stringent rules can’t offer complete protection. No states cover enrollees in self-funded health plans. That’s a big hole, because many employer-sponsored health plans are self-funded. They’re left out because those plans are subject to federal regulations that preempt the states. Many also exempt ambulance services.

That shows that what’s needed is a federal law. And that’s where the roadblocks remain.

The measure currently on the table in Congress, the No Surprises Act, is a revision of a bill proposed in May 2019 by a bipartisan coalition headed by Sens. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) and Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) and supported by the House leadership under Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco).

In its current version, the measure loosens the original bill’s requirement that non-network ER and behind-the-scenes specialists be limited to the network rates negotiated by doctors in the patient’s health network.

The new version provides for a negotiated settlement of disputed charges and for arbitration if providers and a patient’s health plan can’t reach agreement. Arbitrators are instructed to take into consideration the median in-network rates for the designated services, which suggests that the result will be fairly close to those rates.

Like the original bill, the new version also mandates that out-of-network charges be applies to a patient’s health insurance deductible and out-of-pocket maximum.

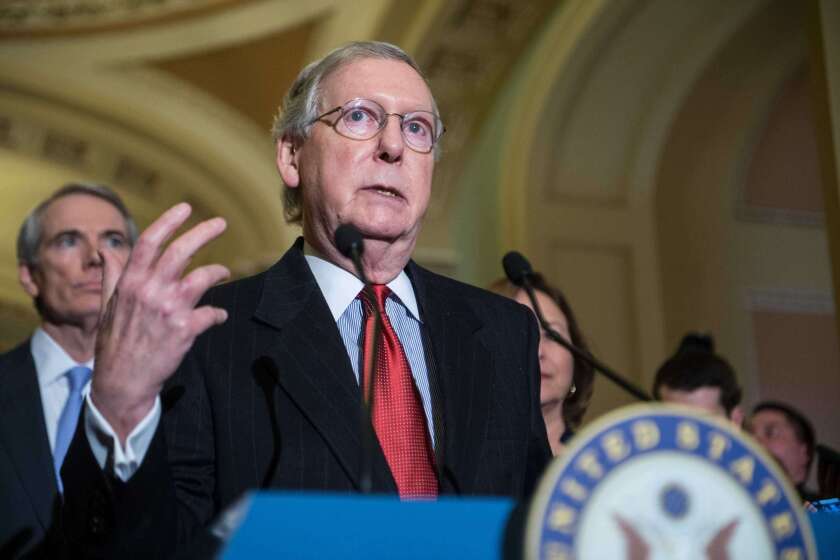

Cassidy and Hassan, in a letter cosigned by 25 Senate Republicans and Democrats, this week asked Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) to add the bill to year-end spending legislation.

“There will never be a broader bipartisan, bicameral solution to ending surprise medical billing and we should deal with it now,” they wrote. “Patients cannot wait any longer.”

The pandemic is destroying state and local budgets, as GOP refuses to help.

Even President Trump has expressed support for an end to the practice, through a Sept. 24 executive order calling for legislation by the end of the year.

That brings us to the AMA’s opposition. As it often does, the organization paid lip service to the idea of “protecting patients from the financial impact of unanticipated medical bills,” then poured cold water on “the bill in its current form.”

The organization’s main cavil — that the measure will have inordinate impact on small medical practices — is largely a smokescreen. The AMA’s concern that the negotiation and arbitration process will be a burden on small practices is fair, medical experts say, but those provisions can be tweaked after the bill is passed.

It’s also true, as the AMA contends, that placing limits on surprise billing by non-network providers will drive down reimbursements for in-network providers, too.

That’s because the threat to go out of network and charge patients sky-high rates gives providers a cudgel to hold over insurers in their negotiations over network status. Remove the right to “balance-bill,” and you’ve taken away that leverage.

But the AMA’s depiction of mom-and-pop medical offices as the prime victims of restrictions on surprise billing is misplaced, at best. The prime generators of surprise bills are practices increasingly being bought up by firms such as EmCare and TeamHealth backed by private equity investors.

These firms are determined to squeeze reimbursements until they scream for mercy. A 2018 study by Yale University scholars found that “after EmCare took over the management of emergency services at hospitals with previously low out-of-network rates, they raised out-of-network rates by over 81 percentage points.”

A century ago, Sinclair Lewis predicted how America would botch the coronavirus crisis.

The survey also found that EmCare paid hospitals to accommodate its billing practices in the form of “an 11 percent increase in facility payments after EmCare entered a hospital,” in part by increasing charges to patients for imaging services.”

The strategy of TeamHealth, the study found, was to use “the threat of out-of-network billing to secure higher in-network payments”: The firm would go out-of-network, jack up prices, then rejoin an insurer’s network after negotiating rates that averaged 68% higher than its previous in-network rates.

It’s unclear whether the AMA is merely carrying water for well-funded private equity firms. Its opposition to the legislation may be simply a case of its doing what comes naturally.

“The AMA has been against anything that might control costs, forever,” Adler says. “So this is probably not surprising.”

It’s also true that the public has been waiting for a remedy to surprise billing for what seems like forever. Everyone who matters is in favor of the Cassidy-Hassan approach, except the AMA. It’s time to thank them for their sincere concern, and move ahead without them.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.