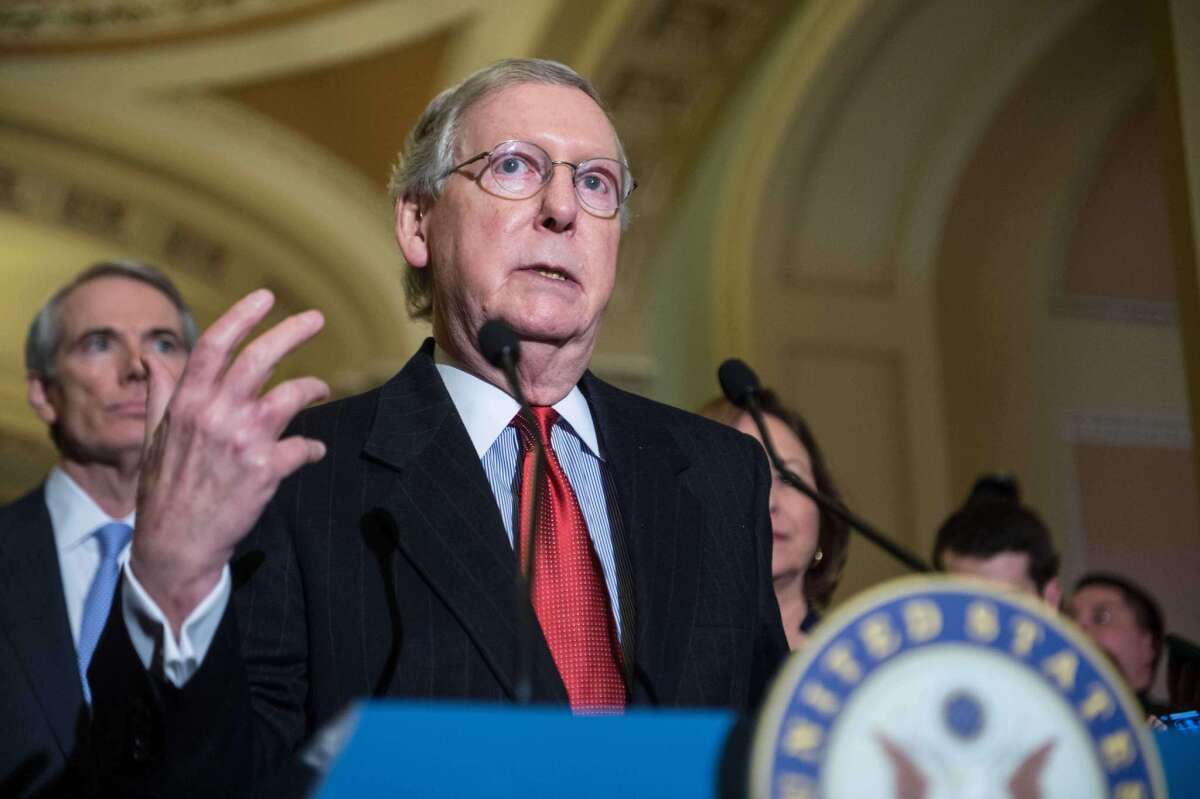

Column: State and local budgets face a pandemic-related meltdown. Why won’t Republicans help?

While every thinking person is rightly worried about the prospect of a third U.S. wave of COVID-19 cases and deaths, one should take a moment to contemplate a pandemic-related disaster in which the first wave is just beginning.

That’s the meltdown of state and local government budgets produced by the higher costs of dealing with the crisis combined with the collapse of revenues.

Over the next year or so, states and local governments could face budget shortfalls of as much as $650 billion, or one-fifth of their pre-crisis budgets, said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics.

If anyone is making the argument that tax revenues are not showing an impact, that’s demonstrably untrue.

— Matt Szabo, deputy chief of staff to L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti

The fallout is already being felt in state and municipal layoffs and cutbacks in public services. Since January, state and local governments have reduced payrolls by 1.1 million workers, or more than 5.5%.

Employment may be creeping up in the private sector, but it’s not returning nearly as fast in the public sector.

More cuts are in the offing. In the city of Los Angeles, for example, where a hiring freeze has been in effect for months with no end in sight, all departments have been instructed to draw up layoff plans.

Civilian employees will shoulder 18 unpaid furlough days in the current fiscal year to produce a savings estimated at $104 million from the overall general fund budget of $6.7 billion.

“The projections are that state and local governments will be laying off 2 million to 3 million more workers,” says Bharat Ramamurti, one of the four members of the congressional committee overseeing relief disbursements from the CARES Act, which was enacted in March. “From a purely economic perspective, that’s catastrophic.”

The nationwide pain could be averted, or at least ameliorated, by an infusion of aid from the federal government. Unlike most states and local governments, the federal government isn’t required to maintain a balanced budget, meaning that its capacity to spend borrowed funds is theoretically unlimited.

State and local employment collapsed for the second month in a row, raising doubts about a national recovery

But no such assistance is on the horizon, thanks largely to Republican resistance on Capitol Hill and in the White House.

House Democrats in May passed the so-called Heroes Act, a $3-trillion pandemic relief bill that includes more than $900 billion for state and local governments. The measure got the cold shoulder from Senate Republicans.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) — who has rushed with cynical haste since the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to place a nomination of a replacement before his chamber — scoffed that his party caucus had not “felt the urgency of acting immediately” on coronavirus relief.

The one notable aid program Congress enacted for states and local governments — the Municipal Lending Facility, administered jointly by the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department — has gone almost entirely unused because potential borrowers consider the loan terms insupportably punitive. Indeed, the terms are far more stringent than those the Fed has imposed on corporations it is helping with coronavirus bailouts.

Of the $500 billion available, only $1.67 billion has been lent out — to two borrowers, the state of Illinois and the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The program expires Dec. 31.

Republicans generally have asserted that state and local revenues seem to have held up pretty well in the first half of the year despite the coronavirus crisis, rendering further aid unnecessary.

But those revenue figures largely reflected taxes due from 2019, before the crisis hit. A crash in 2020 personal incomes is likely to show up next year, as will a plunge in property tax collections, reflecting reassessments downward of commercial real estate properties because of this year’s surge in vacancies and arrears in rent payments.

“If anyone is making the argument that tax revenues are not showing an impact,” says Matt Szabo, deputy chief of staff to Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, “that’s demonstrably untrue.”

In July and August, the first two months of the city’s current fiscal year, business tax receipts are down by $24.6 million, or 6.7%, compared with expectations. Hotel taxes are down by $9 million, or 5.7%, sales taxes by $8.4 million, or nearly 15% and parking fines by $18.5 million, or 7.1%, thanks to a policy of reduced enforcement during the pandemic crisis.

All told, the city’s shortfall from expected general fund revenues for those two months came to $86.6 million, or 7.6%. The full-year budget for 2020-21, which was originally pegged at $6.7 billion, is likely to fall short by as much as $400 million, Szabo says.

The GOP reaction to pleas for help from states and local governments has been nakedly partisan and plain ludicrous. McConnell has labeled such assistance “blue state bailouts.” President Trump, in his usual crass and ignorant manner, asked via Twitter why taxpayers should be “bailing out poorly run states (like Illinois, for example) and cities, in all cases Democrat run?”

The truth is that most states had built up healthy rainy day funds amounting to nearly 10% of state revenues before the pandemic, Zandi reported. COVID-19 annihilated those reserves in a matter of months.

As Rep. Donna Shalala (D-Fla.) noted during a Sept. 17 hearing of the congressional commission, of which she is a member, her home city of Miami went into the crisis with a surplus of $20 million. “COVID-19 wiped that out, and now we face a huge deficit.”

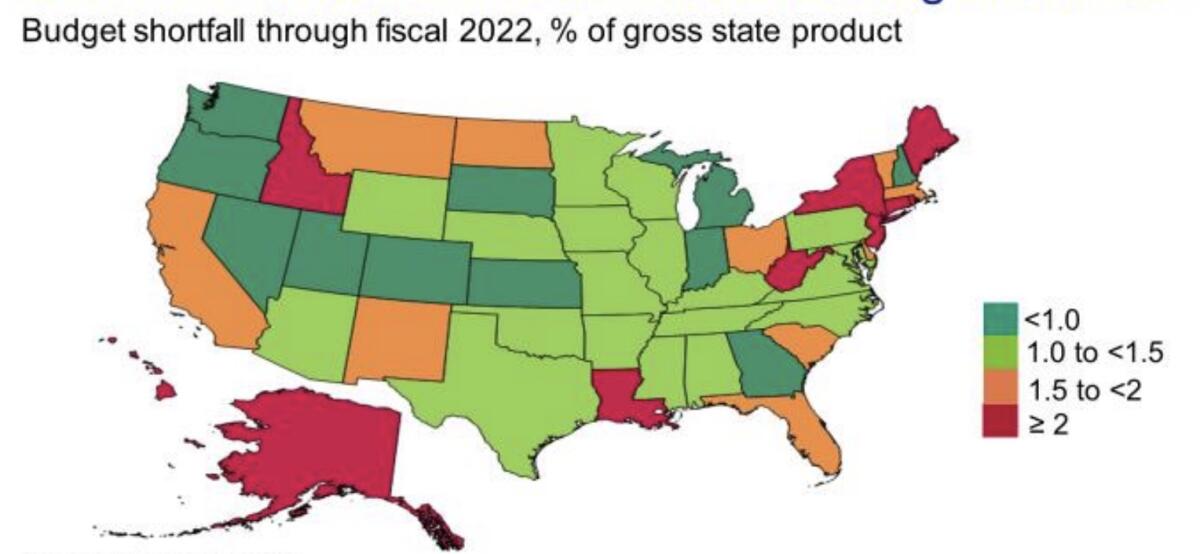

It’s also a fact that pandemic-related budget carnage won’t honor partisan boundaries. In testimony at the commission hearing, Zandi pointed out that among the states most firmly in the budgetary crosshairs are those dependent on energy industries, such as Alaska, North Dakota, Louisiana and West Virginia, and on travel and tourism, such as Florida. These are all red states.

Evidence of the effect of state and local government spending on overall economic growth is easy to find: Just look at the Great Recession.

From the crash of 2008 through 2012, state and local payrolls shed nearly 600,000 jobs; to keep pace with population growth, they should have added more than 500,000. That contributed to what UC Berkeley’s Labor Center labels “one of the weakest economic recoveries on record.”

Before the economy recovers, GOP wants to stop giving aid

The resulting damage to state and local services was widespread, striking most directly at residents most dependent on those services — low-income households.

Cuts in various categories were imposed by 46 states and the District of Columbia, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: 31 cut healthcare programs, 29 and D.C. cut programs for the elderly and disabled, 34 states and D.C. instituted cuts in higher education.

Aid for states and local governments would ripple through the economy, affecting even public entities not in line for direct assistance. The L.A. Unified School District has been spending its own funds to provide free meals for families — 62 million meals thus far, of which as many as one-third are going to needy adults at a cost of about $50 million.

“We have not received a nickel from the city, county, state or federal government for adult meals,” LAUSD Supt. Austin Beutner told me. Nor has the district received financial help for the internet access it is providing for schoolchildren’s households at an estimated cost of $150 million or the COVID testing program it is instituting to enable schools to open, estimated at $150 million.

LAUSD, like other districts, may become a collateral victim of a budget meltdown at the state level, where revenue collapse converted a projected $6-billion budget surplus to a deficit of about $54.3 billion.

The Legislature rejected Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposal to cut $8 billion in K-12 and community college funding, replacing it with a plan to defer about $12.5 billion in state reimbursements, leaving districts to carry those expenses themselves in the meantime.

“The crisis gets defined as a money problem, but it’s a values problem,” Beutner says. “Now as a health crisis is becoming an educational crisis, what’s the moral imperative? The first-grader who doesn’t learn to read on time has a lifetime of consequence. Education is a path out of poverty for millions of kids.”

The most notable failure of government assistance to states and local governments may be the Fed-Treasury Municipal Lending Facility. At the Sept. 17 commission hearing, Ramamurti observed that the Fed’s crisis lending to corporations carried vastly more generous terms than those offered to municipalities.

The Fed purchased bonds of the cigarette maker Philip Morris, for example, at an interest rate of only 0.75% over four years. But it demanded 1.93% interest and repayment over only three years from the New York MTA.

This “punitive” pricing of the lending “does not make it a viable option for municipal issuers,” Marion Gee, president of the Government Finance Officers Assn., told the commission.

Ramamurti, a former advisor to Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), maintains that there is no legal reason why the Fed and Treasury can’t adjust the terms of their municipal lending to match those offered to corporate borrowers.

No reason, perhaps, other than ideology.

“If you are part of the political party whose overarching goal is to reduce the size of government, then you don’t view this as a crisis but as an opportunity to force states into massive spending cuts that otherwise they wouldn’t do,” Ramamurti says.

“You view the end of nutrition programs and housing programs not as a crisis but as a positive outcome. That is the view of many people in the Republican Party these days.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.