U.S. faces an uphill effort in helping build an Iraqi force that can retake Mosul

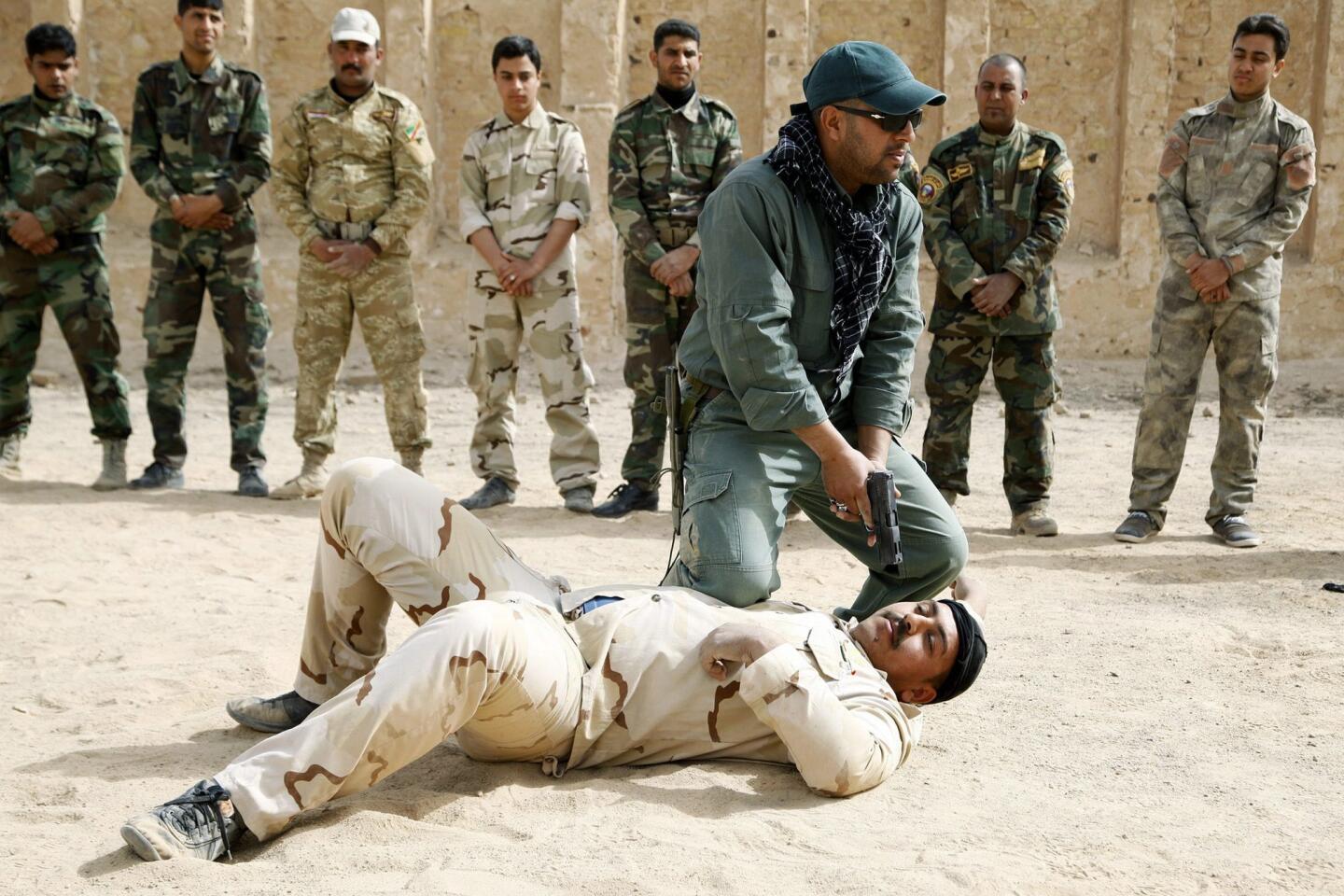

reporting from BESMAYA RANGE COMPLEX, Iraq — As machine guns rattled Thursday from a nearby firing range, Iraqi recruits at this dusty base outside Baghdad trained on tactics, radios, firing mortars and tanks before a bevy of visiting Pentagon brass.

But off to the side, their trainers, mostly from Spain and Portugal, said the soldiers often show up late for training courses or don’t show up at all.

“The last group we had here was a complete disaster,” said Spanish army Maj. Ignacio “Nacho” Arias. “They would come and go without permission.”

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

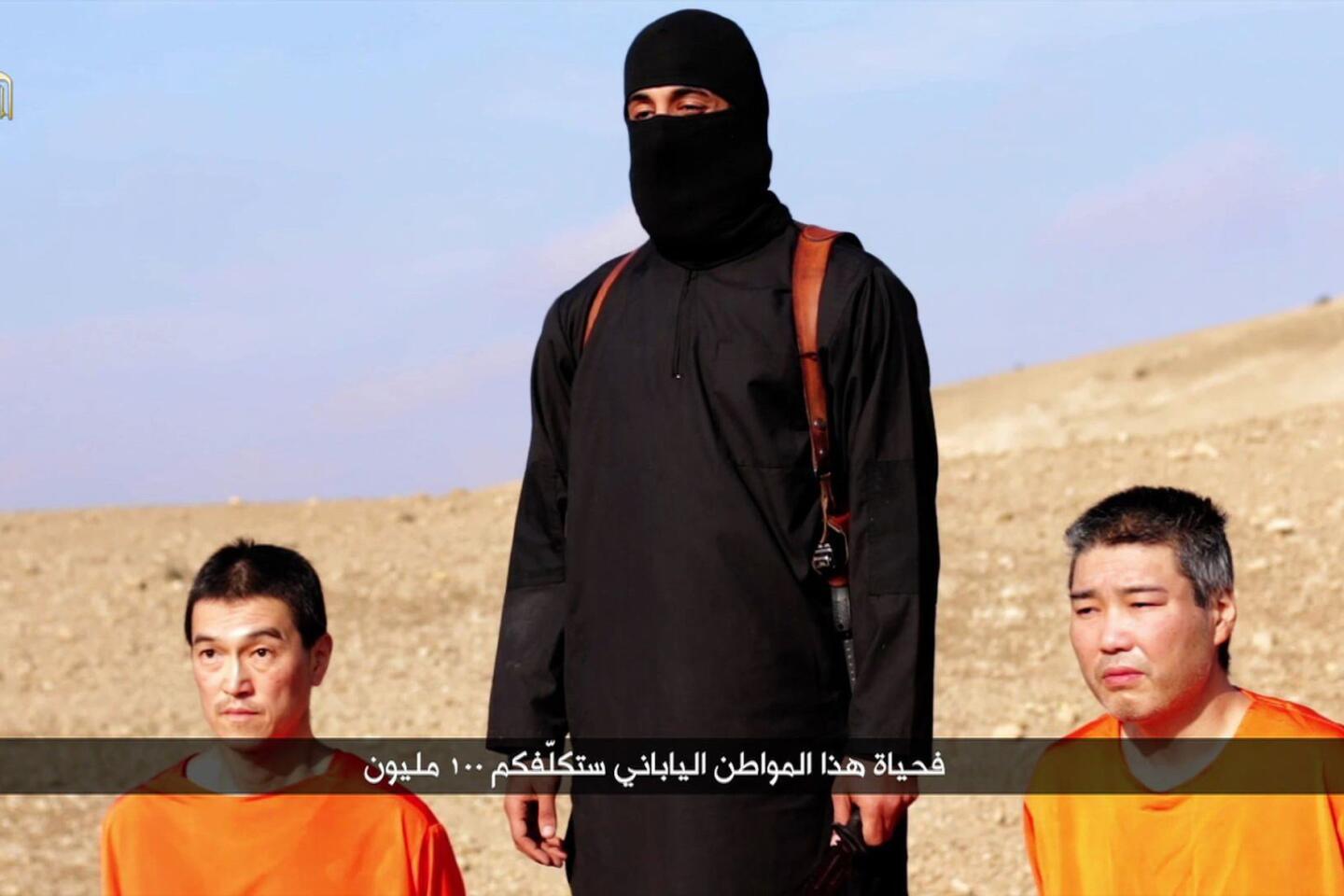

The troubles at this training base reflect broader difficulties in building an Iraqi ground force capable of pushing entrenched Islamic State fighters out of Mosul, the militants’ self-declared capital in Iraq, a priority for the White House and Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Abadi’s government.

The Pentagon announced in March 2015 that an Iraqi offensive on the strategic city was all but imminent. But those ambitious plans were repeatedly shelved as Iraqi troops struggled to push the militants out of smaller cities and towns.

Iraqi forces finally launched their long-delayed assault toward Mosul last month. It quickly stalled.

The sluggish pace has frustrated U.S. commanders and White House officials, who had hoped to recapture the heavily defended northern city and deal a decisive blow to the militants before President Obama leaves office in January.

Obama made it clear this week that he isn’t very optimistic.

“My expectation is that by the end of the year, we will have created the conditions whereby Mosul will eventually fall,” he said Monday in an interview with CBS News.

“We’re not doing the fighting ourselves, but when we provide training, when we provide special forces who are backing them up, when we are gaining intelligence … what we’ve seen is we can continually tighten the noose,” he added.

As part of the push, the Marines deployed about 200 troops and four 155-millimeter howitzer cannons on March 17 to a newly created outpost called Firebase Bell near Makhmour, where U.S. advisors are training Iraqi troops for the assault on Mosul.

Two days later, Islamic State forces fired Katyusha rockets at the firebase. One landed in the compound and killed Staff Sgt. Louis Cardin, a 27-year-old field artilleryman from Temecula, Calif., and wounded eight other Marines.

Pentagon officials did not disclose establishing the forward artillery base until they announced Cardin’s death. The Pentagon later released photos showing the Marines firing the field artillery at what it said were Islamic State infiltration routes.

Visiting Baghdad this week, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter announced that the Pentagon would send 217 more military advisors to Iraq and allow them to accompany Iraqi troops at the battalion level, and thus far closer to the front lines, instead of mostly being confined to Iraqi division headquarters.

That boosts the official total to 4,087 U.S. troops in Iraq. But that tally doesn’t include commandos and what the military is calling temporary deployments. U.S. officials say more than 5,000 U.S. military personnel are in Iraq.

Carter also said the Pentagon would increase its logistical support for the Iraqi military and would deploy several Apache attack helicopters, which are designed for close air support, as well as long-range artillery to aid in the fight.

In addition, the U.S. would provide $417 million to the Kurdish regional government in northern Iraq, he said. Most of the money is intended to pay Kurdish militiamen who have been key allies against Islamic State but who don’t always get paid.

Iraqi leaders appear daunted by the prospect of assaulting a major urban center, according to U.S. officials, and for good reason. Several thousand militants are said to be defending the city and have set hundreds of booby traps in houses and streets.

“We anticipate they [Islamic State] will fight it out to the death,” said a U.S. counter-terrorism official in Washington who spoke on condition of anonymity in discussing internal assessments. “If you are the Iraqi army, you have to face that.”

Abadi’s fragile government in Baghdad has struggled to rebuild its army since entire divisions fled before the insurgent onslaught in 2014. A defeat at Mosul would undermine government authority and shift momentum back to Islamic State.

Although the militants remain capable of launching offensives, U.S. planners believe the battle has shifted against Islamic State in recent months.

Under attack by Iraqi troops backed by coalition airstrikes, the militants were forced out of Ramadi, west of Baghdad, from Hit, a provincial capital northwest of Ramadi, and key positions near Sinjar in northern Iraq. A U.S. special operations task force is conducting raids against the group’s leaders.

Leading any assault on Mosul will be Iraqi troops trained here at Besmaya and at several other bases. Many apparently have little or no previous training and lack sufficient weapons and ammunition.

On Thursday, Iraqi soldiers took turns operating two aging Russian tanks on the Romeo 2 firing range. One after another, they clambered aboard the Soviet-era T-72s and aimed at a target a few hundred yards away.

The cannons stayed silent, however, because the trainees had not been issued any ammunition.

“The most important thing for training is tank rounds and we don’t have it,” complained Maj. Mohammed Abdul Kareem Kadim, an officer with Iraq’s 9th armored division. “How can we train? We need the Iraqi government to bring equipment to us.”

Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr., chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, watched with Lt. Gen. Sean MacFarland, who heads the U.S. campaign in Iraq and Syria from Baghdad.

It was Dunford’s third trip to Iraq since October, and he said he wanted to take stock. He asked MacFarland about the Iraqis’ will to fight.

MacFarland responded that young soldiers are often eager to take the fight to the militants and are let down and frustrated with officers who fail to press forward in combat.

“It’s like Napoleon said: ‘There are no bad regiments, only bad colonels,’” he said. “They’re brave. They’ll fight if they’re well led.”

The U.S. is also training Iraqi fighter pilots and sharing intelligence for airstrikes. The partnership was on display Thursday at the Combined Joint Operations Center in Baghdad, where coalition officers and Iraqi commanders plan bombing runs.

The low-slung building has dozens of analysts perched behind glowing computer monitors. Five large flat screens streamed real-time video from U.S. MQ-1 Predator drones and two Iraqi drones, which were watching twin warehouses north of Hit.

About 20 militants were said to be building car bombs in the warehouses. Iraqi pilots flying two Russian-made Su-25 fighter jets in the area were given the coordinates and ordered to destroy the targets.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Moments later, they dropped two bombs and the flat screens showed plumes of thick gray smoke.

But when the dust settled, the two buildings stood intact. The bombs had missed by 100 feet or more.

The analysts watched on the screens as the suspected militants ran outside and fled to a nearby palm grove, where they disappeared.

Lt. Col. Jeff McCormack, a Marine in the operation center, said he wasn’t surprised.

“Unfortunately, it happens more times than not with the Su-25s,” he said. “The Iraqis don’t always pull it off.”

Times staff writer Brian Bennett in Washington contributed to this report.

ALSO

Prince, master of rock, soul, pop and funk, dies at 57

How are Pennsylvania’s GOP delegates selected? Most voters don’t have a clue

Days before her death, wrestling star Chyna posted a rambling YouTube video

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.