Residents return to recaptured Old City of east Aleppo. Except the city they knew is gone

Reporting from Aleppo, Syria — The ablution fountains, where worshipers would wash before prayers, had long run dry and still stood in the center of the Ummayad Mosque of Aleppo, the fountains’ domed tops leaking shafts of light from the pinpricks caused by bullet holes.

Around the fountains lay small chunks of masonry and shards of jagged metal, byproducts of the warfare that ravaged this ancient metropolis for more than five years.

But at least for now the guns were silent, and on Saturday dozens of people cut off from this part of the city by the fighting returned to survey the damage to the mosque that opened in 717.

“I feel pain because of what happened to my city,” said Jumaa Khalifeh, a well-dressed lawyer, as he gazed at a pockmarked portico.

“This scene, this area ... it pains young and old, and hurts the foe even before the friend.”

Four months ago, Abdullah Muhaisini, a Saudi cleric and the spiritual godfather of many Islamist factions that once held sway here, was interviewed in the mosque’s vast black-and-white tiled courtyard. He vowed the rebels would oust troops loyal to Syrian President Bashar Assad from all of Aleppo.

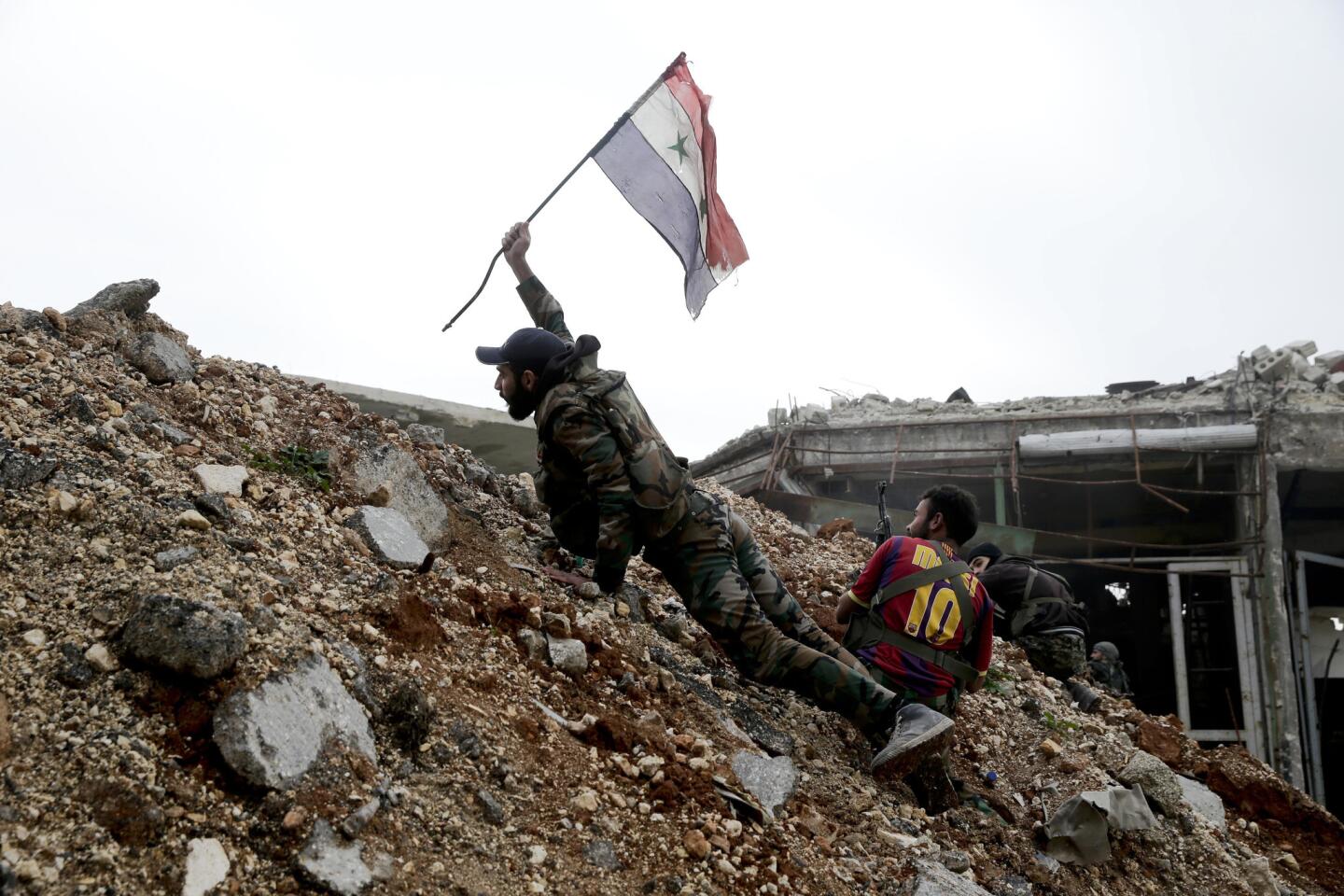

Instead, government forces, backed by Russian air power and thousands of militiamen from as far away as Afghanistan, slowly advanced, leaving the rebels with a scant square mile of territory before they finally capitulated this month.

On Saturday, thousands of rebel fighters and their families remained inside eastern Aleppo, waiting on yet another iteration of an evacuation agreement that had allowed more than 8,000 residents to leave this week for opposition-held territories. That deal appeared stalled once more.

Now, mere yards from where Muhaisini had spoken so confidently, Aleppans posed for selfies before the scarred façades of the mosque.

One woman murmured a soft prayer of thanks as she led her young daughter by the hand through the worn-down archway leading to the majestic building’s interior.

I endured 35 years of working abroad so I could buy the merchandise I had here. And now it’s gone.

— Riyad Shawa, Aleppo resident

The rebels had entered Aleppo one year after the start of the uprising against Assad and seized large portions of the Old City in late 2012. The city came to represent competing visions of modern Syria — either the opposition’s capital, or a powerful reaffirmation of Assad’s grip on the country.

A precarious climb to the mosque’s roof revealed the fruits of the government’s victory — everywhere in the Old City, which was classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1986, one could see rubble, cracked rooftops and singed walls. It seemed no structure had been spared.

The mosque’s northern exit opened into the nexus of shattered streets in the heart of the Madina Souq, where merchants had traded everything — fabrics, copper, soap — since the 14th century (and had made the city known to figures as distant as Shakespeare).

Nearby sat a tank turned upside down, balancing on its turret, an especially popular objet d’art for more selfies.

Off to the side, three men stood before a mountain of rocks, all that remained of the front of Khan Harir (the Silk Market).

“It’s finished. I want to commit suicide. Nothing is left,” said Mohammad Huskol, a dyspeptic 58-year old man with morose blue eyes.

His friend Riyad Shawa gave a bitter chuckle when asked if he could rebuild.

“You think I have money to do this again? I endured 35 years of working abroad so I could buy the merchandise I had here,” he said. “And now it’s gone.”

Their story was not unique: All over the Old City quarter, nervous shopkeepers, eager to inspect the remains of their businesses, stepped, climbed and crawled through the devastated collections of shops known as khans.

One textile business owner, Mohammad Assi, navigated from memory through walkways made even more labyrinthine by the barriers the fighters had put up.

“Is your place OK?” he asked a passerby, another shop owner on a similar quest.

Finally, he found his shop — heavily damaged, but still standing.

“I’ll build this in six months,” he said breezily. “It’ll be fine.”

All around him, walls and storefronts were scribbled with graffiti. Some vowed to “stomp Bashar.” Others declared this area to be controlled by Ahrar Marea or Omar bin Abdul Aziz Battalion – some of the dozens of opposition factions that once patrolled these streets.

On the second floor of Venetians’ Khan (the one-time home of the consul of Venice) was the headquarters of another rebel group with the Western-supported Free Syrian Army, the Battalion of Suleiman’s Soldiers.

It bore all the signs of a hasty retreat during breakfast.

Jars of Aleppo’s famous pepper paste stood near plastic containers of rotting dates and a bowl of congealed ful (fava bean paste), where a wasp now lay half-submerged.

Yet other residents of these neighborhoods had chosen to stay, unable or unwilling to escape.

“There was no bread. The [opposition] cut off the water, but I didn’t leave,” said Abdul Latif Jisri, a garrulous 63-year old man, sitting in front of his empty grocery store and caressing a cat.

His home was destroyed in the violence three years ago, but he had taken his elderly mother with him to another place close by.

“I couldn’t leave her. I never even considered it,” he said, then apologized for not being able to serve his surprise guest any coffee. “No gas or water, you see.”

Up the street, in the Mshaatiyeh neighborhood, tired-looking residents stood in shambling lines before a house which had been turned into a nursing home.

It now also served as a food distribution center run by a local charity, the Ihsaan organization, with support from the World Food Program.

“Different rebel groups would come here, wanting to take over the home or clamoring to get the food,” said Yusra Mahmoud Hassan, the jovial matron of the facility. The rebels never ran the place — too much of a hassle — so Hassan continued her work. “I didn’t leave for a single minute these last five years,” she said.

As Aleppo residents returned to neighborhoods, they often reflected on the unjust randomness of urban warfare.

“They would fire, and wherever the shell fell, it fell,” said 46-year old Wafaa Fustuq, her raspy voice still audible to a reporter who spoke to her through a hole in the wall next to her house. Her house survived.

Luck had favored the house of Muhyi Al Deen Homsi, a tailor of ornate jalabiyyas, Syrian long robes for men, who lived with his wife and six children in Mshaatiyah.

Just next door towered a pile of rubble. From its side rose a bent metal ladder leading up to nothing.

“The shelling never stopped in this area from both sides, but we only left two weeks ago when the fighting got too intense,” said Homsi.

Despite the lack of water and electricity, he had brought his family back just one week later, fearing looters would take advantage of the chaos. He was too late. His precious gas-powered generator had been pilfered, along with electronics.

But now, as one of his sons pushed a wheelbarrow piled with blankets and clothing to the door, a weak smile appeared on his face.

“The fighting is over now,” he said. “Hopefully everything will return to what it was.”

Bulos is a special correspondent.

ALSO

The U.S. is helping train Iraqi militias historically tied to Iran

Fears of Russia and Trump drive EU leaders to boost defense budgets

Syria’s Assad hails ‘the liberation of Aleppo’ as evacuations begin from devastated city

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.