Reporting from Khazir, Iraq — Families made their way east Saturday, past sniper fire, mortar rounds and the bodies of neighbors, to a new camp set up for those displaced by the battle to drive Islamic State out of Mosul.

They arrived in dump trucks and on foot, carrying their belongings in large bags, wrapped in bedding and tarps.

Relatives were waiting outside the camp’s chain-link fence.

Waeed Ahmed Hussein had not seen his parents and four brothers in almost three years, since the extremists seized the Iraqi city and their nearby village of Gogjali, and he fled.

When Hussein, 32, spotted his father in the camp’s screening area, he rushed over to kiss the elderly man’s hands through the fence.

“Uncle, uncle!” cried his 6-year-old nephew, Idris, sprinting out of the gate to hug him.

Guards ushered the boy back behind the fence, as Hussein wiped away tears.

Families reunite in refugee camp after escaping fighting in Mosul. Video by Molly Hennessy-Fiske / Los Angeles Times

The Hassan Sham camp, about 20 miles east Mosul, opened Friday to help handle the exodus of civilians after government troops battled their way into the city this week.

More than 8,000 people had fled by Saturday, bringing the total number displaced since the offensive began to about 30,000, according to United Nations estimates.

Humanitarian groups had warned before the offensive began nearly three weeks ago that as many as a million people could be displaced, and that camps were unprepared because of lack of funding.

In addition to Hassan Sham, the U.N. refugee agency is building 10 more camps, but only half are ready to receive people.

Hassan Sham now houses about 4,000 people and can accommodate 7,000 more. But with the volume of families streaming in, officials expect they will soon have to build another camp nearby.

More than 200 families arrived Saturday and more than 600 on Friday, said Sadiq Mohammed, deputy camp manager. The Khazir camp up the road was already full of those displaced from eastern villages.

“The influx is massive and ongoing,” said Frederic Cussigh, a senior field coordinator for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Iraqi special forces are locked in a bitter battle for eastern neighborhoods of Mosul, commanders said.

“The [counter-terrorism forces] are fighting inside houses, room by room,” said Brig. Gen. Tahseen Ibrahim, spokesman for the Ministry of Defense, who visited the eastern front Saturday.

Federal police on Saturday defeated Islamic State militants south of Mosul, raising the Iraqi flag in Hamam Ali, but they had yet to fully secure the town, Ibrahim said.

At least 20,000 people had been living there when Islamic State took control, and residents said the militants forced more in from surrounding communities after the offensive started.

“We need to clear the car bombs outside and take care of the people,” Ibrahim said.

For civilians caught in the fighting, the route to safety is a perilous one.

Hussein’s older brother, Saad Ahmed Hussein, said that when the family fled their village east of Mosul on Saturday morning, they were targeted by Islamic State snipers and mortar fire.

Iraqi forces had freed the village, but militants sneaked back in using tunnels near the graveyard, he said.

1/59

Menar Hassan, age 8, cries as doctors try to doctor her wounds after a suicide truck bombing. Her father died at the scene and had to be left in the rubble. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

2/59

Capt. Osama Fuad Rauf, 33, center, and Maj. Mohammed Hassan Abdullah, left, 35, treat a soldier who was wounded in the fight against Islamic State near Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

3/59

Wounded soldiers and civilians are carried into a field hospital. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

4/59

Capt. Osama Fuad Rauf works on a patient as others hold a cellphone for additional light at the Iraqi army’s 9th Armored Division medical clinic. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

5/59

Wafa Abdel Raza, 39, holds her son Mahmoud Setar, 4, as the doctors give him oxygen and and fluids. The boy’s head was badly injured when a truck bomb exploded near their home. “We were sleeping in the house,” said Raza. “The army was close to us and we made food for them. They were waiting behind the house and a suicide car came.” Her son recovered as the night progressed. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

6/59

Maj. Gen. Raad Mohssan Dakhel stitches up a soldier’s face after he was injured by a suicide bomb explosion. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

7/59

Murtada Abdul Amir, right, was struck in the shoulder by the same bullet that hit his friend Muaz Hameed Hussein, left. Capt. Osama Fuad Rauf checks Hussein’s status. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

8/59

Civilians are taken to Irbil hospital. The man at right was taken into custody on suspicion of being an Islamic State fighter. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

9/59

SWAT team member Hussein Ali, 21, sits beside his comrade Bassem Bilal, who was badly injured in a suicide car bombing. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

10/59

Maj. Gen. Raad Mohssan Dakhel treats a soldier hit by shrapnel from a car bomb. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

11/59

At the Iraqi Army’s 9th Armored Division medical clinic, set up in a private home, doctors including Capt. Osama Fuad Rauf, center, gather around the body of a deceased soldier before he is taken to Irbil and on to Baghdad. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

12/59

A woman looks out of a dump truck as it arrives at a U.N. campcarrying more than 50 other women and children fleeing the fightingin Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

13/59

Waheed Ahmed Hussein hugs his mother Sada Muslat, 71, on the day he was was reunited with his parents after a two-year separationwhile they lived in an Islamic State-held area. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

14/59

A truckload of people fleeing fighting in the Mosul area arrives at a United Nations camp. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

15/59

People fleeing violence in Mosul and the surrounding areaarrive at the U.N.’s Camp Hassansham. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

16/59

Waheed Ahmed Hussein, right, greets his relative Adris Mohammed through a fense at Camp Hassansham. They hadn’t seen each other in two years sinceIslamic State took control of Mosul and the surrounding area. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

17/59

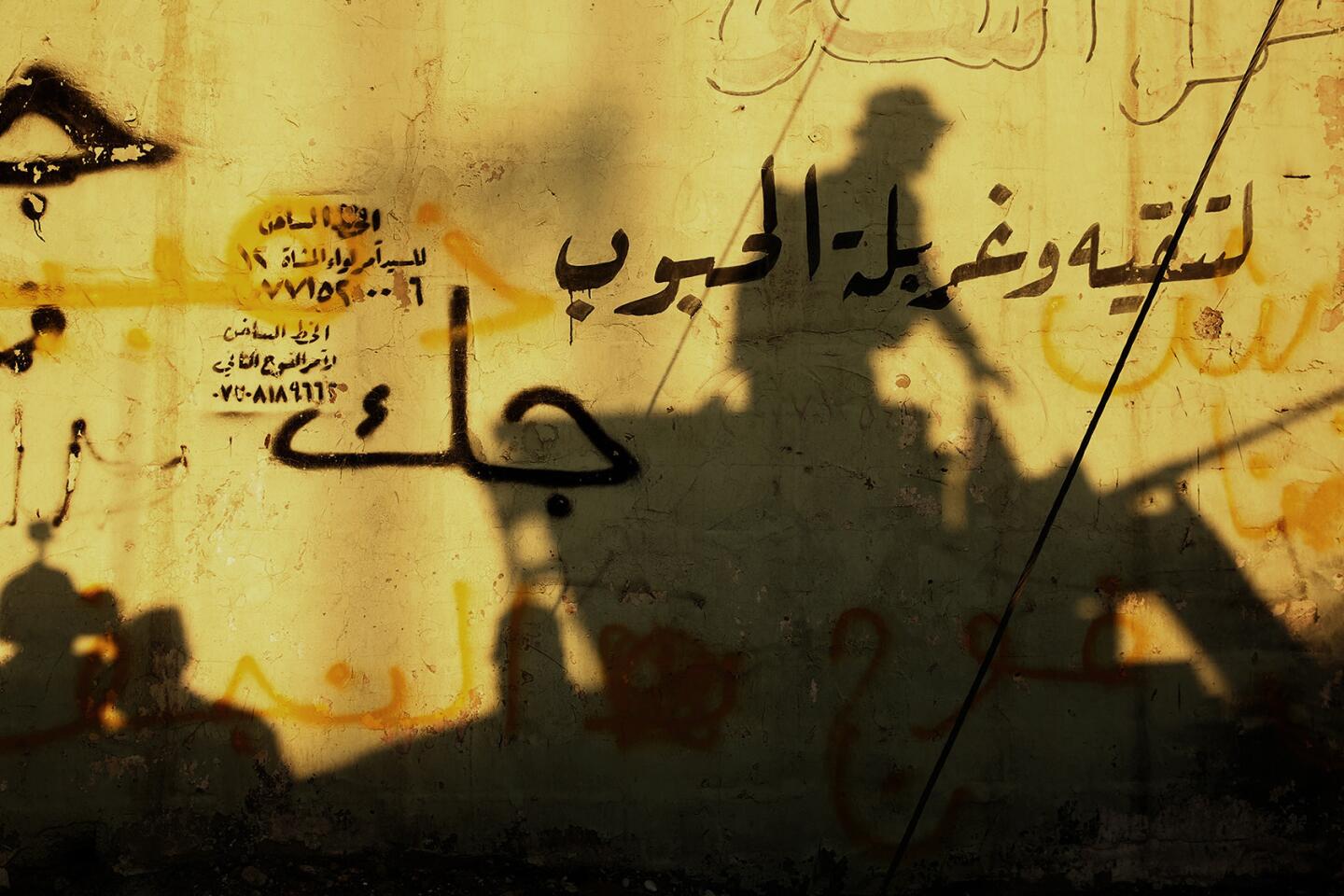

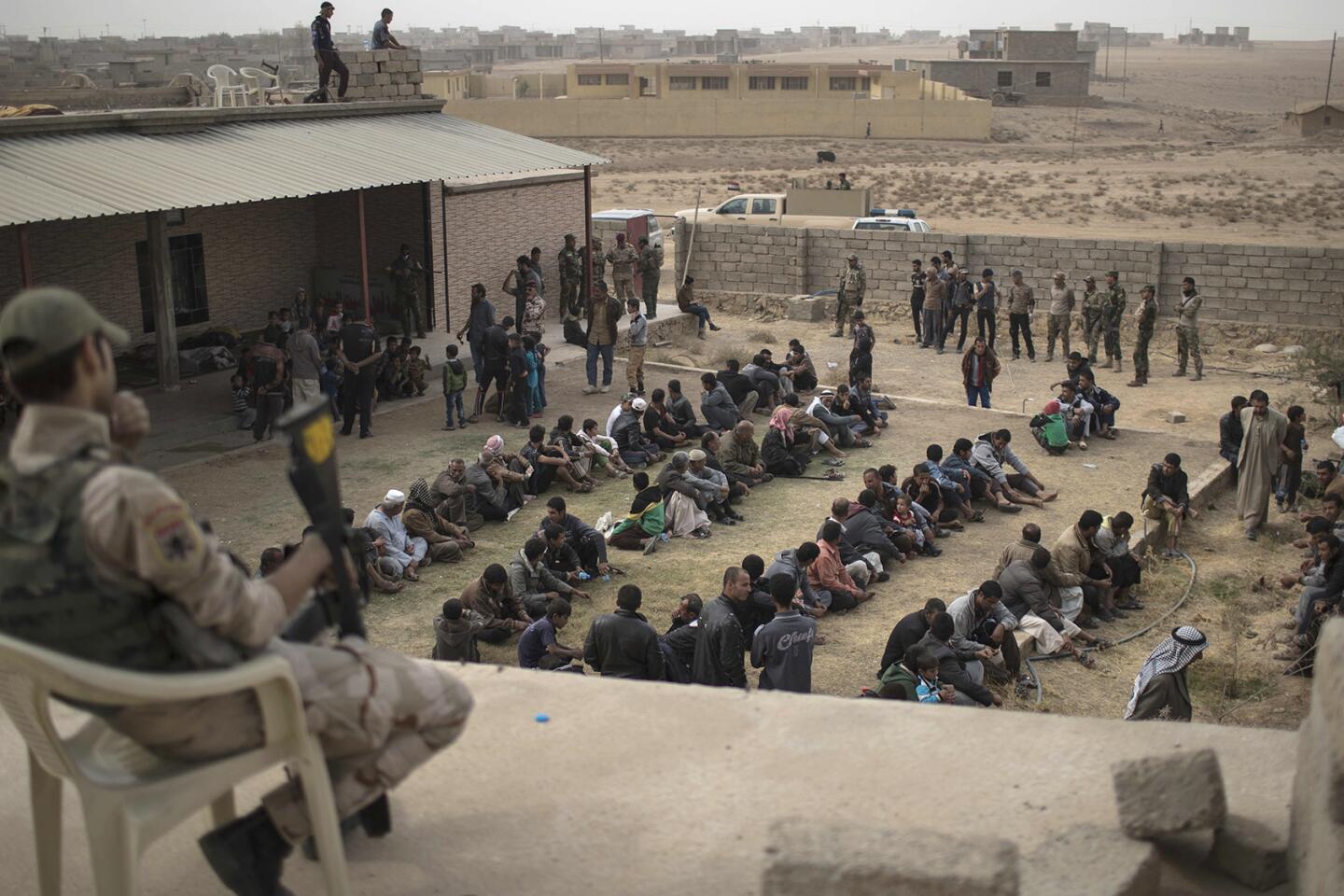

In the town of Salhiya, members of the Iraqi Army and Iraqi police detain and question men who were coming from the direction of Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

18/59

Members of the Iraqi Army and Iraqi police detain suspects in the village of Salhiya, Iraq, who were coming from the direction of Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

19/59

Members of the Iraqi Army and Iraqi police patrol the village of Salhiya. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

20/59

A man flying a white flag with his rear window shattered, is stopped on the road from Salhiya to Qayarrah. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

21/59

On the outskirts of the village of Al Hud, members of the Iraqi Army visit an area where locals say ISIS executed four or five Peshmerga in recent months. Soldiers said another grave site containing more bodies was in the area but was too dangerous to access due to mines. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

22/59

Some of the several hundred civilians who made their way through and out of Gogjali, Iraq, after the Iraqi army retook control of the district in Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

23/59

Iraqi troops patrol Gogjali. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

24/59

Iraqi special forces Lt. Col Ali Hussein Fadil and his men continue to clear the Gogjali district. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

25/59

Iraqi forces patrol the Gogjali district of Mosul a day after it was liberated from Islamic State. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

26/59

Iraqi special forces continue to clear homes in Gogjali on Nov. 2, 2016, after the area was liberated. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

27/59

A girl waves a white flag as she and her family leave Gogjali. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

28/59

Families flee Gogjali after the area was liberated. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

29/59

With no place to sleep, a family rests inside an empty store in Mosul’s Gogjali district, where Iraqi forces defeated Islamic State the previous day. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

30/59

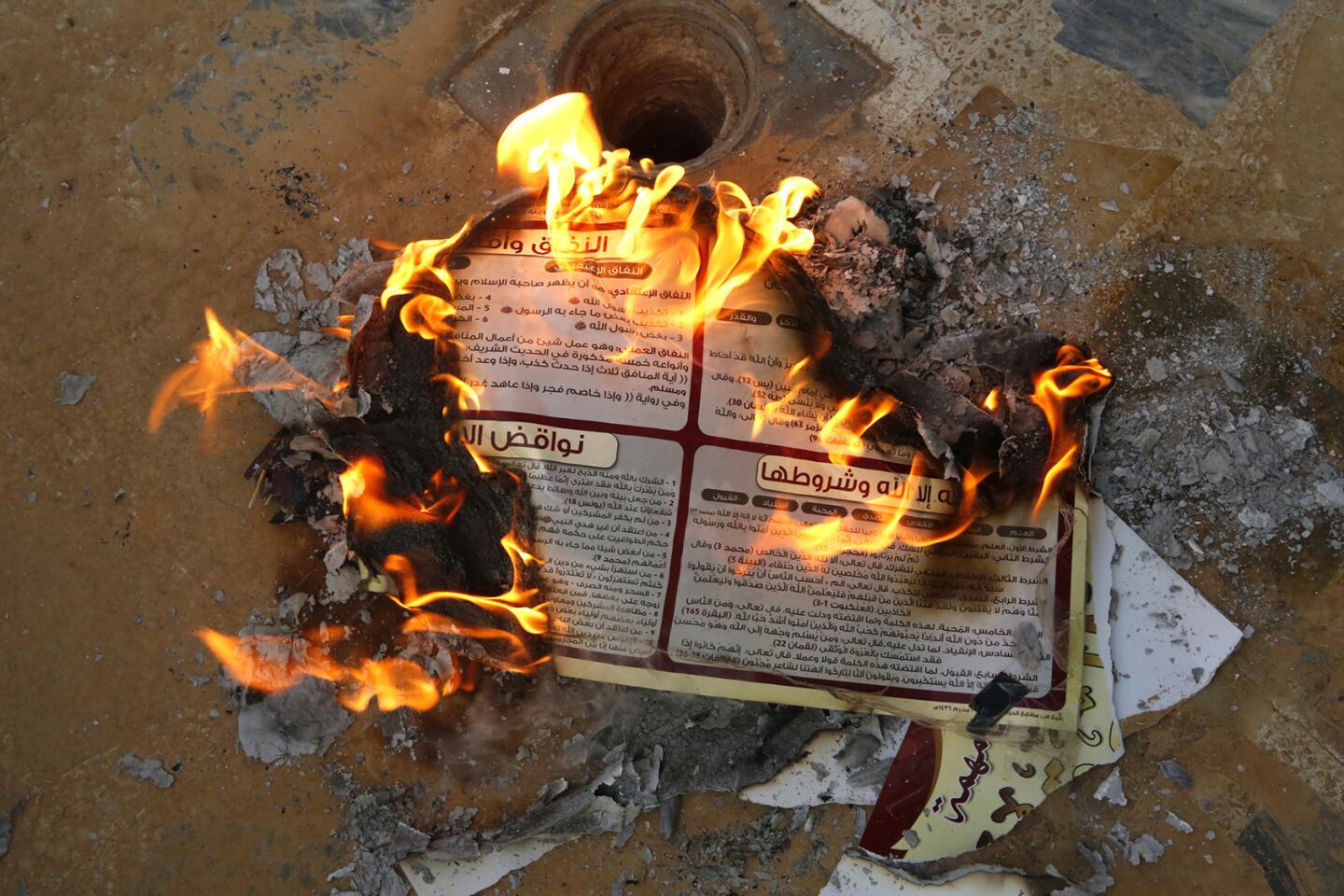

Islamic State posters that were hung in a mosque in the Gogjali district of Mosul, Iraq, are burned the day after the area was liberated from Islamic State control. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

31/59

Popular mobilization units are helping to clear villages southwest of Mosul, Iraq. On Sunday, they launched mortar rounds a little more than a mile from Islamic State fighters who continued to resist their advance on the city. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

32/59

TAL AL-ZAQAA, IRAQ--OCT. 31, 2016--Shiite militia chant before going into battle as they fight alongside Iraq Army forces as they fight ISIS. They launch mortars less than two kilometers from ISIS fighters who continue to resist their advance. (Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times) (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

33/59

Militias known as popular mobilization units fighting near Mosul are made up mostly of Shiite Muslims. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

34/59

Militiamennear the village ofZarqastand by as mortars are launched at Islamic State fighters near Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

35/59

An Iraqi special forces soldier rides in a Humvee with a Shiite religious banner flying behind while moving through recently captured territory on the eastern front inthe fight for Mosul on Oct. 28, 2016. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

36/59

An Iraqi government Humvee window cracked by Islamic State fire on the eastern front in fight for Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

37/59

Lt. Col. Ali Hussein Fadil, center,commands an Iraqi special forces unit in the fight to retake the city of Mosul, including 28-year-old Waleed Abdel Nabi, left. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

38/59

Waleed Abdel Nabi, afather of four, moves through the town of Bartella by Humvee. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

39/59

Waleed Abdel Nabi, right, and a fellow Iraqi special force fighter in the town of Bartella. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

40/59

Waleed Abdel Nabi, 28, clears what appear to be abandoned homes in the advance toward Mosul. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

41/59

An Islamic State tunnel entrance found in Bartella by Iraqi special forces. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

42/59

Iraqi forces patrol in a Humvee east of Mosul as they wait for the next phase of the battle to retakethe city from Islamic State. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

43/59

The remains of a burned car. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

44/59

Sienna Moqtar and her daughter decorate her brother’s grave with rocks. He died last week in the final days of Islamic State in Qayyarah. The bodies of two infant nephews are buried at right. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

45/59

Ibrahim Atea Ahmed, left, and Daham Ahmed survived the Islamic State attack, but their town was left in bad shape. Oil fires continue to burn, set by militants as cover from air attacks. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

46/59

Iraqi soldiers head for the front line. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

47/59

In the village of Faziliya, recently liberated from Islamic State control, Abdul Gafur, 38, embraces his brother Mohammad Abdul Gafur, 40, after not seeing him for more than two years. Peshmerga forces recaptured the village and escorted Abdul to visit his brother. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

48/59

A woman rummages through garbage under smoke-filled skies in the town of Qayyarah. The residents of Qayyarah were liberated from Islamic State forces, but left with destruction and contamination from burning oil wells. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

49/59

Residents of Qayyarah wait for food and water to be handed out, but very little was distributed. The water in town is not fit to drink. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

50/59

Iraqi soldiers now control the town of Qayyarah, where bombing destroyed many shops. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

51/59

An Iraqi special forces member notes the entrance to a tunnel dug by Islamic State forces in the town of Bartella. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

52/59

Bisha Khalil, 60, left, welcomes home her son Zihad Farhan, not shown, to the village of Hurriya, where fighting between Islamic State and Iraqi forces caused many to flee about three months ago. The homecoming was dampened by the kidnapping of Khalil’s 18-year-old son, Ibrahim Farhan, by Islamic State militants a week earlier. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

53/59

Iraqis line up as they return to homesin the villages near Qayyarrah. Many fled their homes three months earlier when government forces battled Islamic State fighters. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

54/59

Children play in a wrecked car in the village of Hurriya, where fighting between Islamic State and Iraqi forces caused many families to leave. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

55/59

As many Iraqis return home, others are fleeing the fighting in villages surrounding Mosul. At a camp for the displaced, about 3,000 people arrived in a week, but many more are expected as the fight for Mosul continues. New arrivals line up for food supplies, provide by the World Food Program. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

56/59

An Iraqi boy, newly arrived at a camp for the displaced, carries food provided by the World Food Program. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

57/59

Soldiers drive through the town of Qayyarah, heavily damaged in the fighting in August and again this month as Islamic State was driven out of town. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

58/59

Batul Khalil, 60, is having breathing problems with all of the smoke and chemicals in the air in her town of Qayyarah. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

59/59

A man leads his cow to find feed in the village of Hurriya, where fighting between Islamic State and Iraqi forces over the last months has left many animals malnourished or dead. (Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

Saad Ahmed Hussein, 34, said he saw a neighbor and his two young children killed in a mortar strike. He also found the bodies of three women killed by mortar rounds. He buried them.

“Islamic State fighters use civilians as human shields. In some cases, Islamic State fighters will go on a roof of a house, and the Iraqi army will avoid targeting them” because of the civilians inside, he said.

He tried to persuade his eldest brother to leave with the rest of the family, but he has several small children, including a toddler. “He said, ‘I prefer to die here,’” Saad Ahmed Hussein said.

Now he is receiving phone calls from friends in Mosul’s eastern Intisar neighborhood saying they too plan to flee, even if they have to live in small tents.

Yunus Qasim, 21, said he managed to escape the west of Mosul with his family this week by pretending to visit an uncle on the east side of the city. But he then found himself dodging bullets that shattered the windows of his uncle’s house Saturday.

“They fired at us,” Qasim said of the militants as he stood outside his new tent at Hassan Sham. “There were mines and suicide car bombs. We saw jets bombing Islamic State positions. We were safe, but other people got injured.”

Qasim said he never received the leaflets that Iraqi forces dropped from aircraft before the offensive urging Mosul residents to hunker down in their homes. Instead, he received Islamic State leaflets warning of the Iraqi army’s impending arrival and saying, “If you stay in your houses, you will die.”

Um Yasir, 36, fled Mosul with her two sons, ages 20 and 17. She said she had been afraid to send them to school or to the mosques for the last two years, in case they were brainwashed by Islamic State.

Now, she worried, “What’s their future going to be?”

She asked to be identified by a traditional nickname, to protect relatives still in Mosul.

As families poured into Hassan Sham on Saturday, Kurdish troops directed them to the fenced-off screening area where they were searched. Then they were assigned numbered tents and departed to find them, clutching slips of paper with their new addresses written in Arabic.

Mohammed Ahmed Hussein, 36, one of the four Hussein brothers at the camp, said he was forced to turn over a precious videotape, which he signed for.

It was a video of his wedding six years ago. “I hope it will be returned to me, because it was a good memory,” he said, smoking his first Gauloise cigarette in years.

After the search was over, his father, Ahmed Hussein, rushed into the camp and down the main gravel road, holding the slip of paper listing the three tents assigned to the family.

“I’m so tired and thirsty. I just want to reach my place,” the 75-year-old said.

Rounding a corner, he found their place at the camp’s edge.

His wife sank onto a tarp outside the tents, despondent about not getting to see her son who had escaped earlier to Irbil.

Suddenly he reappeared and sat down beside her. Camp security had allowed him in. She hugged him close, repeating: “I didn’t think I would see you before I died.”

New arrivals at the camp complained about a lack of food, water, bedding and latrines. They worried about tents filling up, and where their children would go to school.

But many of the children seemed oblivious to their parents’ struggles, exploring the tents, playing ball with stones and hide-and-seek in the latrines.

All the horrors their parents described, they had also endured. It made the stark camp seem more bearable.

As little Idris said, “It’s better than dying.”

1/62

A firefighter works to extinguish an oil well set ablaze by fleeing Islamic State fighters in Qayyarah, Iraq, on Nov. 9.

(Chris McGrath / Getty Images) 2/62

A peshmerga fighter peers through curtains as he and other Kurdish soldiers move into a new house in Bashiqa, Iraq, on Nov. 9.

(Odd Andersen / AFP/Getty Images) 3/62

A peshmerga fighter looks for militants as he and his team move between buildings in Bashiqa.

(Odd Andersen / AFP/Getty Images) 4/62

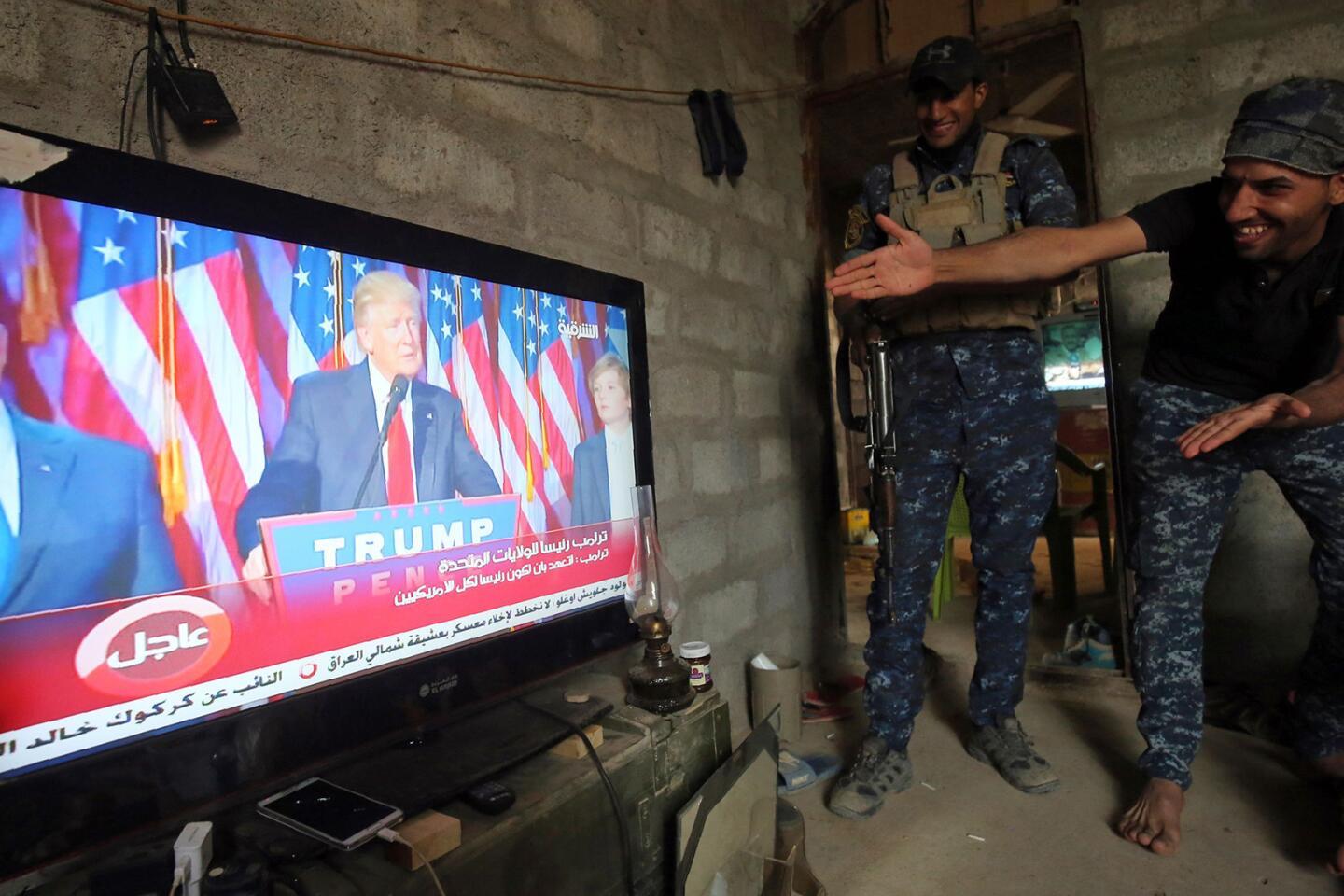

Iraqi forces react as they watch Donald Trump give a speech after winning the U.S. presidential election. They were taking a rest in the village of Arbid on the southern outskirts of Mosul on Nov. 9 during the operation to retake Mosul from Islamic State.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 5/62

Iraqi police try to pull a body from a mass grave they discovered in the Hamam Alil area on Nov. 7 after they recaptured the area from Islamic State.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 6/62

Kurdish peshmerga soldiers fire artillery at Islamic State positions in Bashiqa, Iraq, on Nov. 7.

(Felipe Dana / Associated Press) 7/62

Iraqi forces patrol the Gogjali district of Mosul a day after it was liberated from Islamic State.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 8/62

Families flee Gogjali after the area was liberated.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 9/62

A girl waves a white flag as she and her family leave Gogjali.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 10/62

Iraqi special forces continue to clear homes in Gogjali on Nov. 2, 2016, after the area was liberated.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 11/62

Iraqi special forces Lt. Col Ali Hussein Fadil and his men continue to clear the Gogjali district.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 12/62

Iraqi troops patrol Gogjali.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 13/62

Iraqi army soldiers warm themselves near the Qayyarah air base, south of Mosul, on Tuesday.

(Felipe Dana / Associated Press) 14/62

Displaced people who fled from Islamic State-held territory sit outside a mosque guarded by Iraqi soldiers in Shuwayrah, south of Mosul, on Tuesday.

(Felipe Dana / Associated Press) 15/62

An Iraqi Counter Terrorism Section member drives a vehicles with a broken windscreen as they advance early in the morning near the village of Bazwaya, on the eastern edges of Mosul, on Monday. (Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images)

16/62

Members of the Iraqi counter-terrorism service drive near the village of Bazwaya, on the eastern edges of Mosul, tightening the noose as the offensive to retake the Islamic State group stronghold entered its third week on Sunday.

(Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images) 17/62

Members of the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Service take shelter after a mortar shell hit nearby near the village of Bazwaya, on the eastern edges of Mosul, as they advance towards Iraq’s last remaining Islamic State stronghold on Monday.

(Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images) 18/62

A member of the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Section grimaces in pain as he receives medical treatment after clashes on Monday with Islamic State militants near the village of Bazwaya, on the eastern edge of Mosul.

(Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images) 19/62

Iraqi counterterrorism members carry an injured comrade during clashes with the Islamic State near Bazwaya on Monday. Iraqi forces took control of the village near Mosul. (Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images)

20/62

Children playfully pose for a photo as smoke rises from burning oil fields in Qayara, some 50 kilometers south of Mosul, Iraq, Monday, Oct. 31, 2016. (Felipe Dana / AP)

21/62

A militia fighter prepares to go into battle with his phone and bullets.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 22/62

Popular mobilization units are helping to clear villages southwest of Mosul, Iraq. On Sunday, they launched mortar rounds a little more than a mile from Islamic State fighters who continued to resist their advance on the city.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 23/62

Militiamen chant before going into battle alongside Iraqi army forces as they fight against Islamic State near Mosul.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 24/62

Militiamen near the village of Zarqa stand by as mortars are launched at Islamic State fighters near Mosul.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 25/62

The popular mobilization units received the Iraqi government’s blessing to join the battle that could break Islamic State’s grip in the country.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 26/62

Militias known as popular mobilization units fighting near Mosul are made up mostly of Shiite Muslims.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 27/62

In the village of Faziliya, recently liberated from Islamic State, Abdul Gafur, 38, embraces his brother Mohammad Abdul Gafur, 40. The two had not seen each other since Islamic State forces took control of the village more than two years ealier.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 28/62

Business is brisk at the barbershops in Faziliya after Kurdish forces retook control from Islamic State militants. A bodyguard stands by.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 29/62

Peshmerga, or Kurdish fighters, rest after a recent battle.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 30/62

The remains of a bomb factory can be seen in the village of Faziliya, recently liberated from Islamic State control.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 31/62

A member of the Iraqi armed forces kisses a local boy after Iraqi forces entered the town of Shura, 30 kilometers south of Mosul, Iraq. Iraqi troops approaching Mosul from the south advanced into Shura on Saturday after a wave of U.S.-led airstrikes and artillery shelling against Islamic State positions inside the town.

(Marko Drobnjakovic / AP) 32/62

Iraqi families, who already had been displaced by the ongoing operation by Iraqi forces against jihadists of the Islamic State group, flee Mosul. Iraqi paramilitary forces launched an operation to cut the Islamic State group’s supply lines between its Mosul bastion and neighboring Syria.

(Bulent Kilic / AFP/Getty Images) 33/62

Walid Abdel Nabih, 28, from Nasiriya and a father of four, moves through passageways created by Islamic State to prevent detection by drones. On the eastern front in the fight for Mosul, an Iraqi special forces unit waits for next phase of the fight to clear Islamic State operatives from Mosul.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 34/62

An Iraqi special forces member rides in the turret of a humvee with a Shiite religious banner flying behind him as he patrols Bartella, Iraq.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 35/62

As many Iraqis are returning home, others are fleeing the fighting in villages surrounding Mosul. At Camp JJadh, 3,000 people arrived in the past week, but many more are expected as the battle for Mosul continues. New arrivals line up for food, provide by the World Food Program.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 36/62

Children play in a dismantled car in the village of Hurriya, where fighting between Islamic State and Iraqi forces has caused many families to leave over the past months. The risk of unexploded weapons is still a concern for many in the area.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 37/62

Soldiers drive through the town of Qayyarah, heavily damaged in the fighting in August and again this past week as Islamic State was driven out of town.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 38/62

Sienna Moqtar and her daughter decorate her brother’s grave with rocks. He died last week in the final days of Islamic State in Qayyarah. The bodies of two infant nephews are buried at the right.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 39/62

Ibrahim Atea Ahmed, left and Daham Ahmed survived the Islamic State attack, but their town was left in bad shape. Oil fires continue to burn, set by militants as a cover from air attacks.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 40/62

Residents wait for food and water to be handed out, but very little was distributed. The water is not fit to drink in the town.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 41/62

Iraqi soldiers head for the front line.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times) 42/62

An Iraqi fighter takes a position on top of a vehicle as smoke rises on the outskirts of the Qayyarah area, 35 miles south of Mosul, during an operation against Islamic State.

(BULENT KILIC / AFP/Getty Images) 43/62

Smoke billows from an area near the Iraqi town of Nawaran, northeast of Mosul, as Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga fighters march down a dirt road during the ongoing operation to retake the city from Islamic State.

(SAFIN HAMED / AFP/Getty Images) 44/62

Iraq’s elite counterterrorism forces raise an Iraqi flag after retaking Bartella, outside Mosul, Iraq.

(Khalid Mohammed / Associated Press) 45/62

Iraq’s elite counterterrorism forces raise an Iraqi flag after retaking Bartella, outside Mosul, Iraq.

(Khalid Mohammed / Associated Press) 46/62

The commander of Iraq Special Forces Lt. Gen Abdul Ghani al-Asadi during an interview on the Bartila front line, after the city was liberated from Islamic State militants.

(AHMED JALIL / EPA) 47/62

Iraqi Special Forces take up position in Bartila front line, after the city was liberated from Islamic State militants.

(AHMED JALIL / EPA) 48/62

Iraqi soldiers ride in a truck advancing through the desert on the banks of the Tigris River toward the Islamic State stronghold of Mosul.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 49/62

Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga fighters fire rockets from a mobile launcher near the town of Bashiqa, about 25 kilometers northeast of Mosul, on Oct. 20, 2016.

(Safid Hamed / AFP/Getty Images) 50/62

A member of Iraq’s elite counterterrorism forces advances with his unit toward the city of Mosul, on Oct. 20, 2016.

(Khalid Mohammed / Associated Press) 51/62

A villager walks on a bare street as smoke from oil fires nearby turn the sky black in the Qayyarah area, about 60 kilometers south of Mosul, on Oct. 19, 2016.

(Yasin Akgul / AFP/Getty Images) 52/62

Iraqi soldiers look on as smoke rises from the Qayyarah area south of Mosul on Oct. 19, 2016, as Iraqi forces take part in an operation against Islamic State to retake Mosul.

(YASIN AKGUL / AFP/Getty Images) 53/62

A man takes a selfie in front of a fire from oil that has been set ablaze in the Qayyarah area south of Mosul on Oct. 19, 2016, during an operation by Iraqi forces against Islamic State to retake Mosul.

(YASIN AKGUL / AFP/Getty Images) 54/62

An Iraqi sniper wearing his camouflage in the village of Bajwaniyah village, about 30 kilometers south of Mosul, on Oct. 18, 2016.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 55/62

Smoke rises from an explosion as Iraqi forces retake the village of Bajwaniyah from Islamic State on their way to Mosul.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 56/62

Iraqi soldiers inspect a tunnel in a building in the recaptured village of Shaquoli, about 35 kilometers east of Mosul, on Oct. 18, 2016.

(Safin Hamed / AFP/Getty Images) 57/62

An Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga fighter stands amid the rubble of a destroyed building on Oct. 18, 2016, in the village of Shaqouli, east of Mosul, after it was recaptured from the Islamic State group.

(Safin Hamed / AFP/Getty Images) 58/62

A man carries a baby at a refugee camp in Syria’s Hasakeh province for Iraqi families who fled fighting in the Mosul area on Oct. 17, 2016.

(Delil Souleiman / AFP/Getty Images) 59/62

Lt. Col. Ali Hussein, right, addresses Iraqi security forces leading a government offensive that began Monday to oust Islamic State from the city of Mosul, the extremist group’s last major stronghold in Iraq.

(Molly Hennessy-Fiske / Los Angeles Times) 60/62

An Iraqi police officer inspects his weapon at the Qayyarah military base, about 60 kilometers south of Mosul, on Oct. 16, 2016, amid preparations for the offensive to retake the city from Islamic State.

(Ahmad Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 61/62

Iraqi forces head north toward Mosul on Monday, part of the operation to retake the city from Islamic State.

(Ahmad al-Rubaye / AFP/Getty Images) 62/62

Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga fighters fire a mortar shell from Mount Zardak.

(Safin Hamed / AFP/Getty Images) [email protected]

Twitter: @mollyhf