More than half of the world’s 21 million refugees live in these 10 countries

Wealthy nations are shirking their responsibility to refugees and exacerbating the global crisis, according to a report published Monday by Amnesty International.

The report, “Tackling the global refugee crisis: From shirking to sharing responsibility,” calls on some nations to increase the number of refugees they host so that no single country is overwhelmed.

The nations hosting the bulk of refugees are Jordan, Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, Ethiopia, Chad, Uganda, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to Amnesty.

The human rights organization said more than half of the world’s 21 million refugees live in those countries. But those nations account for less than 2.5% of the world’s GDP, the monetary value in goods and services produced by countries, creating a situation that is “inherently unsustainable.”

About 30 countries offer some kind of refugee resettlement program, according to the report.

“Wealthier countries are not doing their fair share,” said Tarah Demant, senior director of the identity and discrimination unit at Amnesty International USA. “We’re looking at a global crisis that affects everybody, but the burden of responsibility is falling on countries that don’t have the resources.”

The report does not suggest a specific resettlement number for any country. But Amnesty International was among several rights groups that supported a United Nations proposal this year to resettle 10% of the world’s refugees annually. Human rights groups lambasted wealthier nations for rejecting the target.

The Amnesty report says determining what would be a country’s “fair share” for resettlement could be based on criteria such as national wealth, population and unemployment numbers. Other considerations could be a country’s safety record, its existing claims by refugees seeking asylum and whether refugees would have access to the same judicial processes and protections as the host population, Demant said.

The report acknowledges that this solution probably would be “condemned by some as too simplistic.” But “not by those countries that are hosting hundreds of thousands of refugees,” the report says.

According to the report, refugees on all continents face crushing challenges such as living in makeshift shelters without adequate food, water and sanitation facilities, as well as detention and persecution.

Many “are living in grinding poverty without access to basic services and without hope for the future,” the report says. “Not surprisingly, many are desperate to move elsewhere.”

But as things currently stand, their chances of being resettled in wealthy, industrialized nations are slim.

Many of the world’s wealthiest nations host the fewest refugees, “both in absolute numbers and relative to their size and wealth,” according to the report.

The United Kingdom, for example, has accepted about 8,000 Syrians since 2011, while — according to the latest U.N. statistics — more than 670,000 Syrians are registered as refugees in Jordan. The Arab kingdom has a population almost 10 times smaller than Britain and just 1.2% of its GDP, Amnesty said.

Most of the almost 5 million people who have fled Syria since the civil war started more than five years ago live in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt, according to U.N. data.

The U.S. has taken in nearly 12,000 Syrian refugees since the start of the conflict, according to U.S. State Department figures.

Roger Waldinger, director of the Center for the Study of International Migration at UCLA, said rich nations have an obligation to take in refugees because they are signatories to the U.N. convention on refugees and “they have all accepted the doctrine of not sending them back.”

“It is in their interest to bind themselves into an agreement to take more refugees,” said Michael Clemens, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Center for Global Development. “It is in their interest to show they stand for principles of common humanity.”

Studies show that refugees could be economically advantageous for wealthy nations once the preliminary difficulties of resettlement are overcome and they are allowed join the labor force and contribute to society.

“There is a pattern that they are a short-term burden and a long-term benefit, and the long-term benefit outweighs that initial burden,” Clemens said.

Amnesty pointed to Canada, which has resettled almost 30,000 refugees since November 2015, and Germany, which accepted more than 1 million refugees last year, for showing leadership commensurate with the scale of the refugee challenge.

Some opponents to increasing the intake of refugees fear foreign terrorists would slip into their country. Others say money used to resettle refugees should be spent on domestic needs.

In some countries, citizens fear an influx of people from divergent cultures would dilute their nation’s culture and practices. Many insist that Middle Eastern refugees should be resettled in nearby oil-rich Persian Gulf states where the language, terrain and customs are more similar than that of Europe.

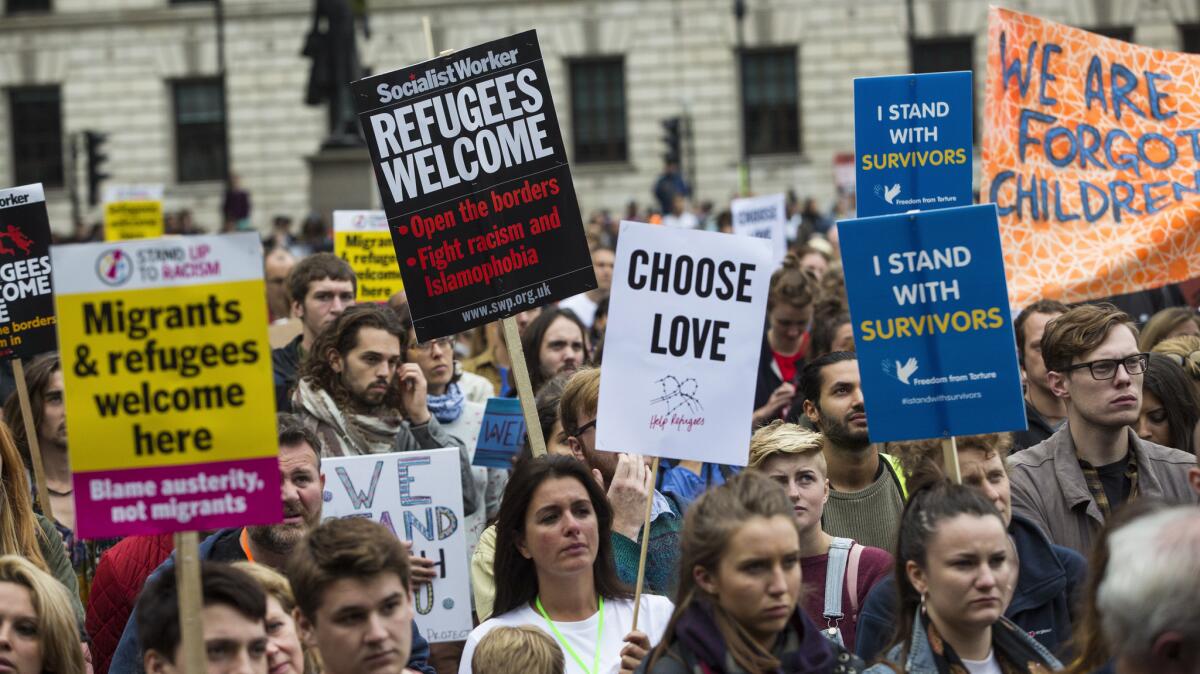

The Amnesty report says that in some countries, the population is subjected to misinformation fueled by a politics-driven narrative of xenophobia, opposition to immigration and concerns over security.

A global survey of more than 27,000 people commissioned by Amnesty this year found that 80% of people worldwide would welcome refugees in their country.

“We’re at a moral moment where we can either be leaders or accomplices in this crisis,” said Demant. “Without doing more we are contributing to that crisis.”

For more on global development news follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.