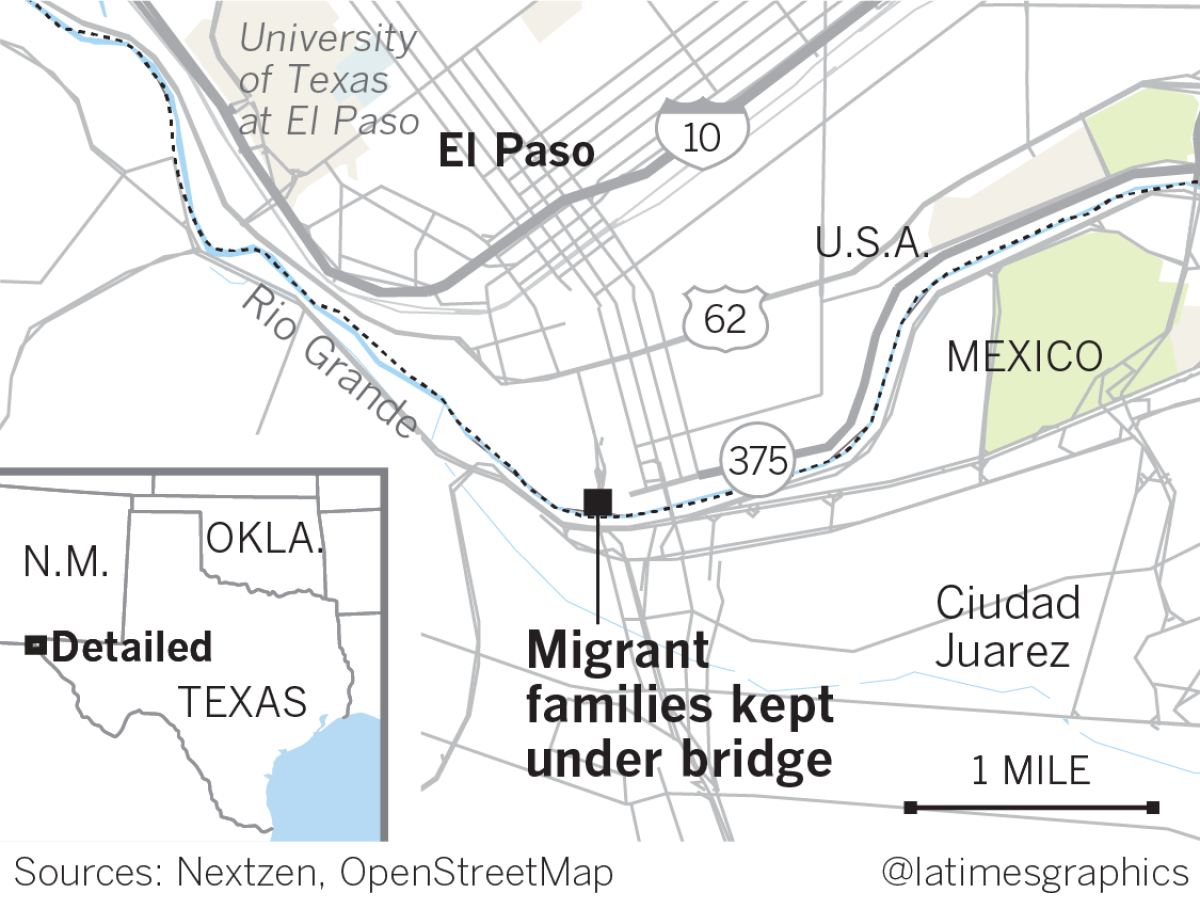

U.S. border authorities hold migrant families in a pen under an El Paso bridge

Darkness had fallen, but few in this cramped outdoor detention camp would sleep.

Most of the migrants huddled in the cold desert air had nothing but thin blankets of insulated plastic to protect them from the wind. Rows of families, including small children and babies, lay directly on the dirt floor. Some had been living like this, exposed to the elements under an El Paso bridge, for four days, held there by U.S. border authorities.

The hastily erected holding pen, U.S. officials say, is an extreme but necessary response to a recent increase in Central American families crossing illegally into the country to ask for asylum. A Customs and Border Protection spokesman on Friday called the pen a temporary “transitional shelter” and said it was established last month.

Migrant advocates call it the latest in a string of inhumane practices targeting asylum seekers. They say that exposing families and young children to unsanitary conditions and chilly desert nights puts them in danger.

In December, two migrant children died in the agency’s custody. On Friday, the El Paso medical examiner released an autopsy that found that one of the children, 7-year-old Jakelin Caal of Guatemala, died of strep-induced sepsis.

“We are doing everything we can to simply avoid a tragedy in a CBP facility,” Customs and Border Protection Commissioner Kevin McAleenan said this week, adding that many migrants are ill when they arrive. “But with these numbers, with the types of illnesses we're seeing ... I fear that it's just a matter of time.” Jakelin’s family has disputed that she was ill before she and her father were taken into custody.

The scores of families shivering each night under the bridge in El Paso highlight a seismic shift in the type of migrants seeking to reach the U.S. in recent years — as well as the failures of U.S. policy to adapt to those changes.

A decade ago, the vast majority of people apprehended at the border were single adult men who had been caught trying to sneak into the U.S. But in recent weeks, nearly two-thirds of those detained by U.S. agents have been families who turned themselves in to officials and asked for asylum.

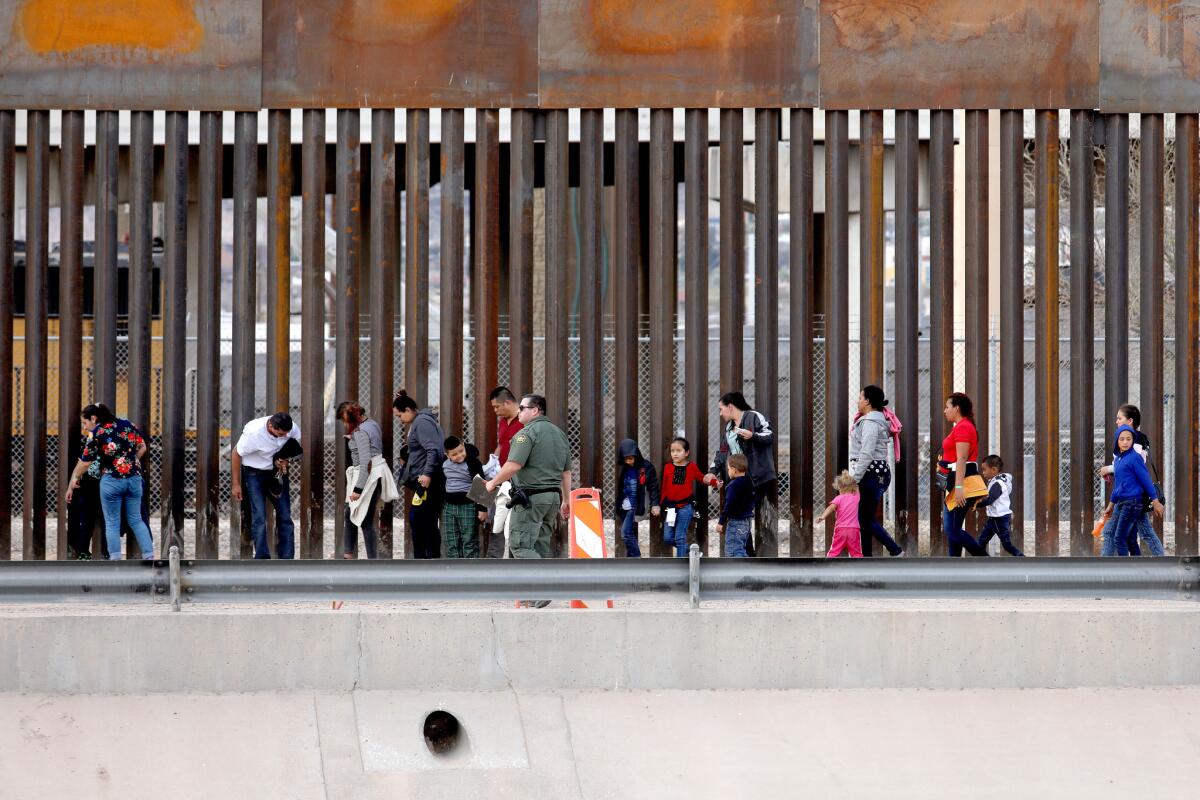

Families have increasingly been crossing illegally to turn themselves in; at official ports of entry, the Trump administration has dramatically limited the number of migrants allowed to present asylum claims.

Customs and Border Protection hit a “breaking point” and has run out of space in which to process asylum seekers, McAleenan said at a news conference in El Paso. An uptick in family arrivals has pushed the overall number of migrants detained at the border to numbers not seen in more than a decade, with an especially large increase here on the far western edge of Texas, he said.

President Trump has repeatedly threatened to shut down official border crossings with Mexico. He said on Twitter on Friday he would do so next week if Mexico failed to stop migrants from reaching the U.S.

But closing border crossings would do little to stop families from exercising their right to seek asylum, since most are crossing between points of entry. Nor would a border wall help; a winding river separates much of the border where Trump wants construction, so a barrier would need to be built several feet north of the actual border, up on a sturdy levee.

Each day here, large groups of asylum seekers have been walking across the shallow river and then waiting on the narrow strip of U.S. territory north of the Rio Grande and south of a newly constructed section of wall. Sooner or later, khaki-clad Border Patrol agents pull up in vans and pick them up.

U.S. officials and immigration experts say the country’s border infrastructure simply isn’t equipped to deal with this new wave of asylum seekers. The Border Patrol’s mission is to detect people seeking to illegally enter the United States, not house and process thousands of asylum seekers each day.

Similarly, the country’s overburdened immigration judges aren’t equipped to quickly try the hundreds of thousands of asylum cases the U.S. expects to see this year. More than 855,000 immigration cases await adjudication, according to Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse; asylum applicants wait on average more than 700 days to see a judge.

Since Trump reversed his policy of separating parents and children at the border last year, families seeking asylum have been processed by immigration officials and then released inside the U.S. with a court date years in the future.

The recent quick release of such families appears to be contributing to increased migration from Central America, with an estimated 1% of the entire population of Honduras and Guatemala on track to be apprehended at the border this fiscal year, according to Adam Isacson, a researcher at the think tank Washington Office on Latin America.

“There is a message that if you think you need to leave, now is the time,” he said.

What is needed, Isacson said, is not more border fencing but more aid to Central American countries to address the root causes of migration, and a mass hiring of new immigration judges to cut case backlogs.

The U.S. has been seeing an uptick of asylum-seeking families and unaccompanied children over the last five years, he said, and U.S. policy must adjust to that.

“This is the new normal,” he said.

Trump has repeatedly criticized the recent crush of asylum seekers, painting them as economic migrants who use the asylum process as a back door into the U.S. At a rally in Michigan on Thursday, the president mocked those who request asylum, including those who say their lives are in danger, calling their efforts to win protection in the U.S. “a big fat con job.”

“This is absolutely an unconscionable way to treat people. You don’t let children sleep under underpasses.”

— Taylor Levy, legal coordinator at Annunciation House

Migrant advocates insist that many of those crossing have legitimate fears of returning to their home countries in Central America — politically volatile places that have some of the highest homicide rates in the world.

The advocates say the outdoor holding center under the El Paso bridge is evidence that the U.S. is not treating migrants humanely.

“This is absolutely an unconscionable way to treat people,” said Taylor Levy, legal coordinator at Annunciation House, a migrant shelter in El Paso. “You don’t let children sleep under underpasses.”

She said her organization had spoken with many migrants who stayed at the makeshift shelter. They complained of not having enough food to eat and of not receiving adequate medical attention, she said. Other migrant advocates in El Paso said they heard similar accounts.

The story of one Guatemalan father who crossed the border into El Paso on March 21 with his 9-year-old son and asked for asylum underscores the complexity of the issue.

Elmer, 32, who gave only his first name because he said he fears persecution back home and from U.S. immigration authorities, promised to pay a smuggler $6,000 to ferry him to the U.S. border.

The smuggler told him to bring his son on the journey, because although single adults who seek asylum are typically detained for months under U.S. policy, families requesting asylum are quickly released.

Elmer said eight of his relatives and 10 of his son’s grade-school classmates had left in a similar fashion in recent months, thanks to rising crime in the city where they live and the falling price of coffee beans, which have hurt farmers like Elmer. In Guatemala, he earned less than $10 a day.

The pair’s long trek north with a series of smugglers was long and often frightening, Elmer said. As they crossed Mexico packed on hot buses, he worried he and his son might be kidnapped by criminal groups known to prey on migrants.

But the worst moment came once they crossed into the U.S. and were corralled into the small outdoor holding pen in El Paso, surrounded by razor wire. There was a tent set up, but it housed only a small portion of the migrants who were there. Border officials say the area is meant as a “transitional shelter,” but Elmer and his son slept outside on the dirt for four days, surrounded mostly by young mothers and fathers with children. Sick people coughed loudly and babies wailed all night.

“We were hungry and cold,” he said. “Those were some of the hardest days of my life.”

The pair were finally processed for asylum and released to a local migrant shelter two days ago. On Thursday afternoon, they sat holding hands in the El Paso Greyhound station, waiting to board the first of several buses that would take them to Alabama, where two of Elmer’s sisters live.

The station was crowded with dozens of migrants who had just been released from federal custody, some of whom, like Elmer, wore bulky ankle monitors over their pants.

As soon as they reached Alabama, Elmer said, he planned to phone his wife, who was home in Guatemala with their younger son.

First, he said, he would tell her he was safe. Then he would urge her not to make the long journey to join him.

The nights outside under the bridge in El Paso had been too difficult, he said. “I don’t want them to run that risk.”

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.