A rural Mexican town grieves for a little girl after the earthquake and wonders why aid was slow to arrive

Reporting from SAN GREGORIO ATLAPULCO, Mexico — When she arrived at the central plaza, desperate to find her missing daughter and husband, there was nothing that Ivonne Natali Rodriguez could do.

The powerful earthquake had collapsed a more than 6-foot-tall stone wall surrounding the colonial-era church here in this rural enclave in Mexico City. The heavy debris had fallen on father and daughter as they walked to the market.

“All I could see was the little feet of my girl,” Rodriguez said. The debris killed her youngest child and left her husband maimed, his right leg mangled. “Some people helped me move the stones.”

Naomi Natali Martinez, who would have turned 6 next month, dreamed of becoming a doctor and going to Paris. The first-grader loved Disney films, dancing and singing.

Little Naomi was one of at least 360 people who died in the magnitude 7.1 earthquake that struck central Mexico on Sept. 19.

Excruciating accounts of death — and uplifting tales of survival — have been emerging as crews continue clearing rubble in Mexico City and the environs, uncovering new bodies each day.

Although attention mostly has focused on hard-hit urban districts, the quake also devastated rural and semirural communities such as San Gregorio Atlapulco, which, while part of Mexico City, has the feeling of a pueblo, situated about 30 miles south of downtown, and reachable only via an unpaved, pothole-scarred strip of road. Many in this community of about 22,000 remain bitter that official quake aid did not arrive sooner.

“It was we the people of San Gregorio who organized to save ourselves and help our people because no one in authority responded,” said Eduardo Perez, 41, who helped pull victims from the ruins on Sept. 19. “The authorities abandoned us. They didn’t arrive till two or three days later.”

The borough delegate, or chief, Avelino Mendez, was chased out of town when he showed up two days after the quake. A day earlier, Mendez had given a nationally televised interview downplaying the injuries and damage in the community, comments that enraged many here.

Cellphone video shows residents heckling Mendez and trying to pounce on him with fists and water bottles as aides provided cover during his visit. The borough chief eventually decamped hastily, jumping into the back of a truck.

To this day, the extent of the damage in San Gregorio Atlapulco — and the death toll — has not been publicly clarified.

In general, Mexican authorities have declined to provide casualty numbers for specific zones or collapsed structures, preferring to release daily national and citywide totals. The practice has led to widespread hearsay and social-media speculation that the death toll is higher than officially acknowledged.

“We don’t know anything — it’s all rumors,” said Rodrigo Acosta, who was sitting on the front steps of his tostada shop in San Gregorio Atlapulco, just across the street from the now-cleared site of a three-story building that collapsed.

How many people, if any, perished in the collapse of the building — which included a busy mini-market on the main floor, along with exercise and billiards establishments upstairs — remains a mystery.

That is also the case with the casualties from the collapse of the wall that surrounded both St. Gregory the Great Roman Catholic Church and the tree-shaded central plaza, or zocalo. Much of the wall, including three towering arches, tumbled to the ground, burying young Naomi, her father, Pedro Martinez, and a number of vendors who traditionally sell vegetables and other items in the shadow of the wall.

Naomi’s mother said she saw at least six other bodies at the site of the collapse. Makeshift shrines of flowers and candles, now sodden with rain, stand near the spots where Naomi and others perished.

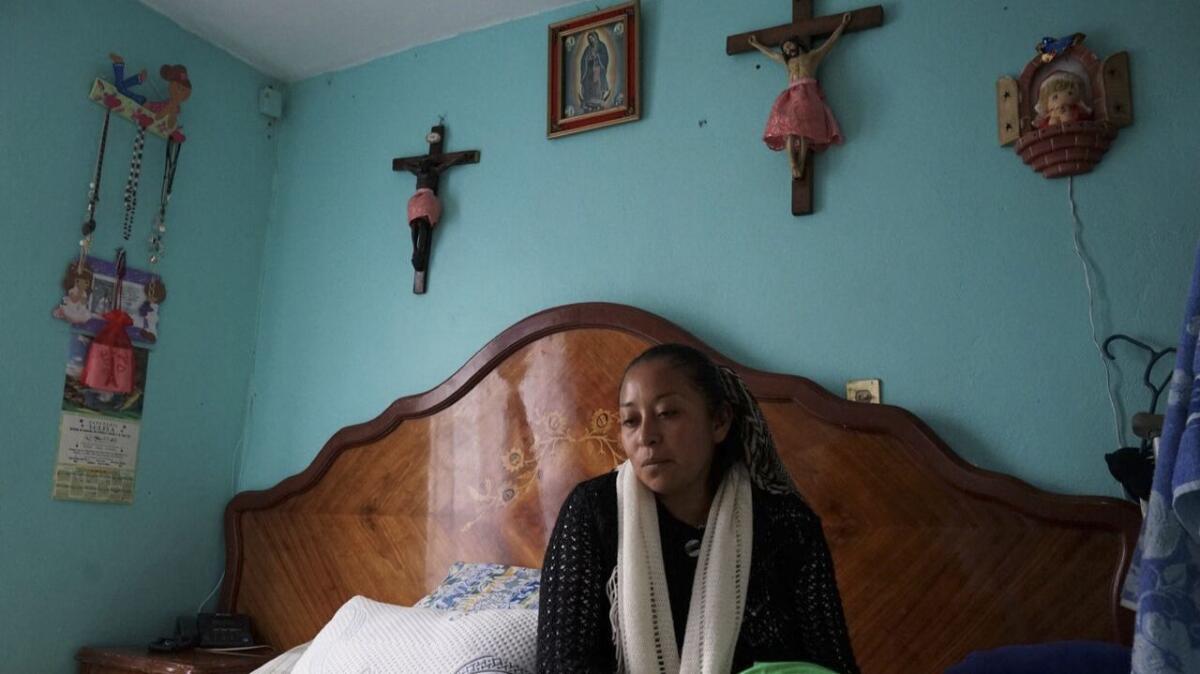

“It is not right that authorities and our delegate are hiding things,” said Rodriguez, who has four surviving children: a 14-year-old daughter and three younger sons.

It was an odd twist of fate that Naomi and Martinez happened to be walking by the wall at 1:14 p.m. on Sept. 19.

Earlier, Martinez had stopped by the girl’s elementary school to pick up Naomi and two brothers. But the boys decided to stay for an after-school book program.

Father and daughter left the school and headed for the market. The route took them past the looming stone wall. Then the earth shook.

“She had a huge stone on top of her,” said Eduardo Galicia, 32, who was among the townsfolk who rushed to help. He runs a chicken stand and just managed to escape under an arch and into the plaza with his daughter before it tumbled.

“The father was there and was shouting desperately, but he was also trapped,” Galicia said. “His legs were covered and he couldn’t move. He was shouting for someone to help his daughter, but the girl was already dead.”

From the family home half a mile away, Ivonne Rodriguez could see dust rising from the town and rushed to the center, fearing the school had collapsed. Her sons were safe. But where were her daughter and husband? Despairing, she eventually made her way to the wall, where Martinez, 39, had been pulled from the debris.

“Where is la niña?” she asked her husband.

He responded: “She is dead. The stones crushed her.”

In the aftermath of the quake, Ivonne Rodriguez embraced the crumpled remains of her child and carried her bloodied corpse to the family home up the hillside.

No ambulance arrived at the scene. Some relatives drove the husband through heavy traffic to two different hospitals, where doctors bandaged the wounded leg but could not perform surgery. By the time he arrived at the third hospital, his vital signs were fading. Doctors elected to amputate the right foot of Martinez, who farms lettuce for a living.

Today, the rubble of the collapsed wall and from other damaged structures has largely been cleared. Kids play soccer in the plaza in front of the church, which lost a bell tower in the quake. Navy tanker trucks provide people with water, and troops keep order on the streets. Aid groups give away food, clothing, toys and other items.

Still, many here seem dazed. Residents wander about like ghosts in surgical masks as protection against the dust. Scores of buildings are damaged.

On Friday, the family held a memorial service for Naomi. Relatives carried a school picture of the girl. Her mother held the child’s favorite doll.

Afterward, the family took part in a procession to Naomi’s grave. At the site, mourners placed a cross, the doll, bouquets of flowers and several balloons, including two with Disney princesses.

After prayers, those assembled gave three cheers to Naomi.

“I have suffered my losses, but so have many others,” the mother said afterward at her home, where a shrine contained many mementos of the girl, including her pajamas, some photos and a white balloon that bore a hand-drawn likeness of Eiffel Tower. “My pain is the pain of my town, of my people.”

Her husband could not attend the memorial. He was receiving additional medical treatment.

“Along with his physical ailments, he is emotionally destroyed,” said his wife. “He feels guilty for the death of the girl. I tell him all the time that he did what he could, that it is not his fault, but he cannot be tranquil. He hasn’t stopped crying, screaming. These have been the worst days of our lives.”

Twitter: @mcdneville

Special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Rio in San Gregorio and Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

ALSO

Rocked by the quake, Mexico’s economy could get a boost from the rebuilding

In one Puerto Rican nursing home, a struggle to get power and keep patients alive

Trump lashes out at Puerto Ricans after mayor’s criticism of administration’s relief effort

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.