On the Ground: Meet the Catholic grocer who helps Mexican Jews keep kosher

Noe Trinidad Chavez, owner of El Tope in San Miguel Tecamachalco, Mexico, prepares zucchinis for platillo a la jardinera, a traditional meal eaten by Sephardic Jews.

Reporting from SAN MIGUEL TECAMACHALCO, Mexico — Noe Trinidad Chavez sat at a small card table gutting zucchinis with a metal corer knife, preparing them to be stuffed with meat and cooked into platillo a la jardinera, a traditional meal eaten by Sephardic Jews.

The 56-year-old, a native of the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, was born and raised Catholic. He had never met a Jewish person in his life until he was 10, when he ventured off to Mexico City for work. There he got a job helping Jewish families with day-to-day needs, such as cleaning and cooking.

Now he’s the owner of two Jewish food shops, including this one that’s no more than 6 feet by 14 feet with a lime-green awning adorned with a Star of David.

The store’s unlikely name: “El Tope,” or speed bump, a tribute to his humble beginnings and where he set up a food cart as a street vendor.

His shop is stocked with produce and packaged products common to Mediterranean diets — eggplant, grape leaves and tamarind syrup he prepares himself.

“It’s hard to find such unique things like these,” Chavez said. “It’s a very small but very important store in the life of the Arab and Jewish community.”

Although Mexico may be known for being the second-largest Roman Catholic country in the world, it’s also home to a small but thriving Jewish population of about 40,000, concentrated mainly in Mexico City. El Tope is among dozens of shops in the town of San Miguel Tecamachalco, west of Mexico City, catering to a Jewish clientele.

A Catholic shrine in the multicultural community of San Miguel Tecamachalco, Mexico.

Chavez can thoroughly explain what keeping kosher entails — what his customers can and can’t eat and when, under Jewish law. He can’t read the Hebrew on the labels of the products that fill his store, but he knows which ones signify they are certified kosher.

In recent weeks he has been preparing for Passover, which began Friday, clearing his shelves of forbidden products and performing the ritual of koshering his utensils by immersing them in boiling water. He refers to the holiday by its Hebrew name, Pesach.

Some store owners might have been put off by having to learn the complicated kosher rituals of an unfamiliar culture as part of their business. For him, Chavez said, it’s the most beautiful part.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Decades ago, San Miguel Tecamachalco was more than just a “little village” and consisted of acres of farmland. Now, it’s hugged on all sides by seemingly endless rows of houses protected by tall, contiguous gates, which line the streets in Lomas de Tecamachalco and other surrounding suburbs.

Sirilina Avelino, who grew up here and runs a small restaurant, watched as the cattle and cornfields disappeared and the small commercial district took their place. As the demographics shifted, Jewish people made their mark on the community, she said.

“When they have their holidays, the town feels it because the majority of their businesses are closed, and the people that work in these businesses, it’s clear they don’t come, they don’t work,” Avelino said as she sipped jamaica, or hibiscus tea, with her family during a lunch break.

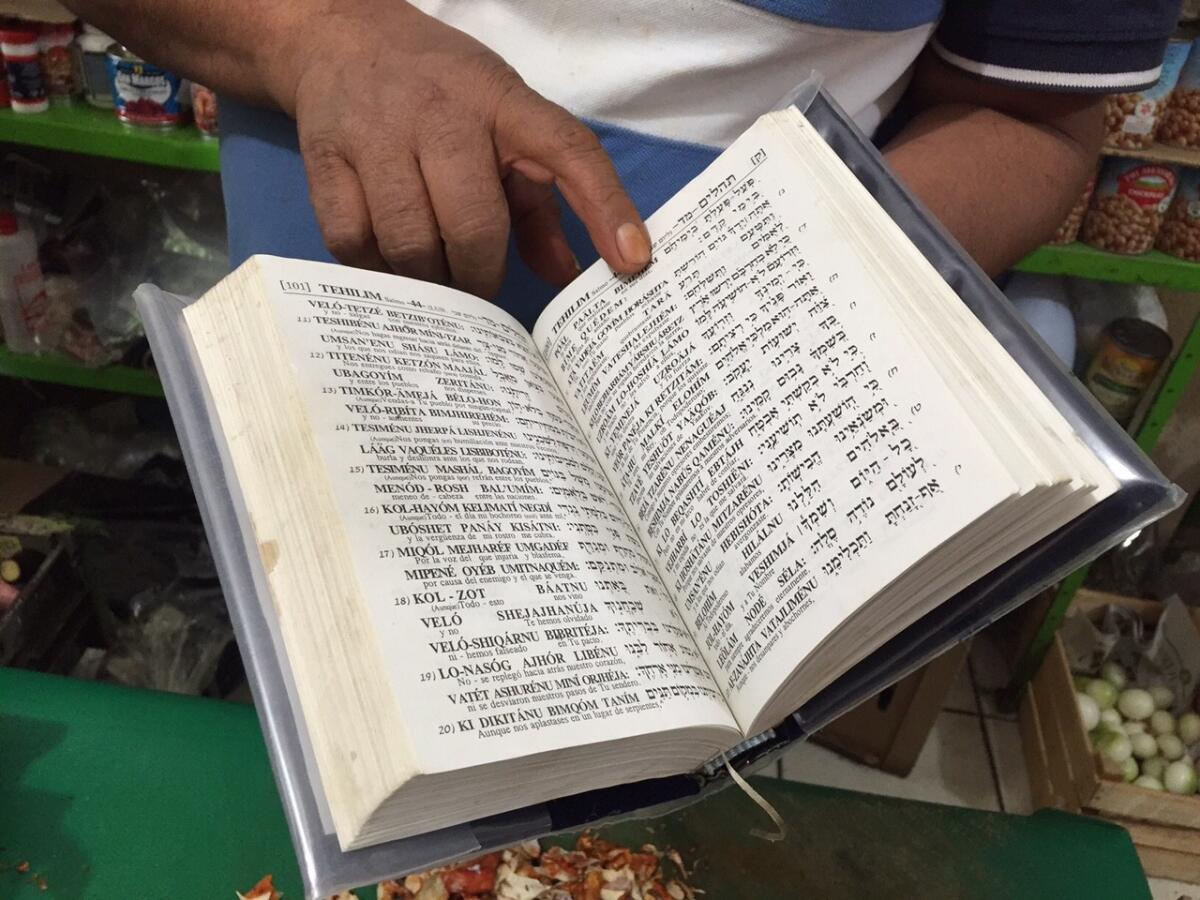

Noe Trinidad Chavez displays a Book of Psalms in Hebrew and Spanish. It was a gift from one of his many Jewish customers.

Next door to her restaurant, Orthodox Jewish families eat lunch in a quesadilla restaurant with a sign bearing a kosher symbol and “B”H” (for Baruch Hashem, meaning bless God in Hebrew). Nearby is a sign of the dual cultures here: a small Catholic shrine with a vase of yellow flowers and a statue of St. Jude.

The closest thing to a full-fledged grocery store in the town is Kurson Kosher, with a bakery, upstairs kitchen, meat counter and shelves stocked with pita bread and tortillas. Falafel balls and assorted kosher tamales share space in the freezers that line the back of the store.

“We don’t abstain from or deprive ourselves of anything that’s Mexican,” said store manager Morris Rudy. “Anything that’s Mexican, we can make kosher.”

A few blocks over, Eli Mordo, 50, an Israeli pizza shop owner, is used to people walking into his store and asking why his pizza is so expensive. Mordo explains that kosher food costs more because it has to be prepared in a special way. Some of his poorer customers can’t afford it.

“I give them another price,” Mordo said, pronouncing his Spanish with the guttural, French-sounding Rs of his native Hebrew. “We all have to be happy, no matter whether you’re Jewish or not.”

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Though waves of Jews arrived in Mexico in earlier centuries, most of today’s Mexican Jews are descended from immigrants who traveled in the 19th and 20th centuries from Europe and the Middle East, said historian Monica Unikel. She has been giving walking tours of the Jewish parts of Mexico City for 20 years.

As they gained wealth in the 1950s through 1970s, many Jews moved west from the city’s historic center to nearby suburbs such as Polanco and Lomas de Tecamachalco.

“It’s a very, very small community, but if you ask someone at the street — anybody — ‘How many Jews do you think there are in Mexico?’ they would say about 1 million because we make a lot of noise,” Unikel said, referring to prominent Jewish people across various professions.

Unlike Jews in other countries, Jews in Mexico have very low rates of assimilation, she said. Most affiliate with a Jewish institution, few marry outside the faith, and about 90% of children attend Jewish schools, she said.

Some of the goods sold at El Tope, which serves a mostly Jewish clientele.

“In the States, in Europe, the Jewish population is going smaller and smaller, but in Mexico it’s always keeping the same because it’s a very close and traditionalistic community,” Unikel said.

At El Tope, among shelves of canned chickpeas and jars of tahini, Chavez has hung a metal hamsa, an amulet with a blue-and-white “evil eye” and two small round bottles filled with green and red “evil eyes.” There’s another wooden hamsa with a metal plate inscribed with a blessing. Protection against evil, they were gifts from Jewish customers.

He keeps another gift, a Book of Psalms in Hebrew and Spanish, near his workstation.

One of his customers is Mery Mercado. Even though she has to deal with parking as uncompromising as downtown L.A., she is still a regular of El Tope.

She comes because of Chavez.

“He knows what we like,” she said, with an armful of produce.

Every now and then, Chavez said, his customers will ask: Given all his interest in Judaism, why not convert? There’s no need, he tells them.

“Religion does not make separations. God does not divide. God is love,” he recalls telling them, interchanging the word “Dios” with the word in Hebrew, “Hashem.” “And the most beautiful thing is to respect their religion and that they respect yours.”

On Fridays, Chavez wishes his customers a peaceful Sabbath, saying, “Shabbat shalom!”

“They also say, ‘Shabbat shalom, Noe!’ As if you were part of their community,” Chavez said, before correcting himself. “Not as if you were — you are.”

Twitter: @taygoldenstein

ALSO

Mexican police tortured suspects in case of missing students, report says

Border Patrol sees increase in number of migrants being detained at Mexico border

Raised in the U.S. without legal status, he attains the American dream — in Mexico

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.