In Mexico, a victory at long last for the left and a two-time loser

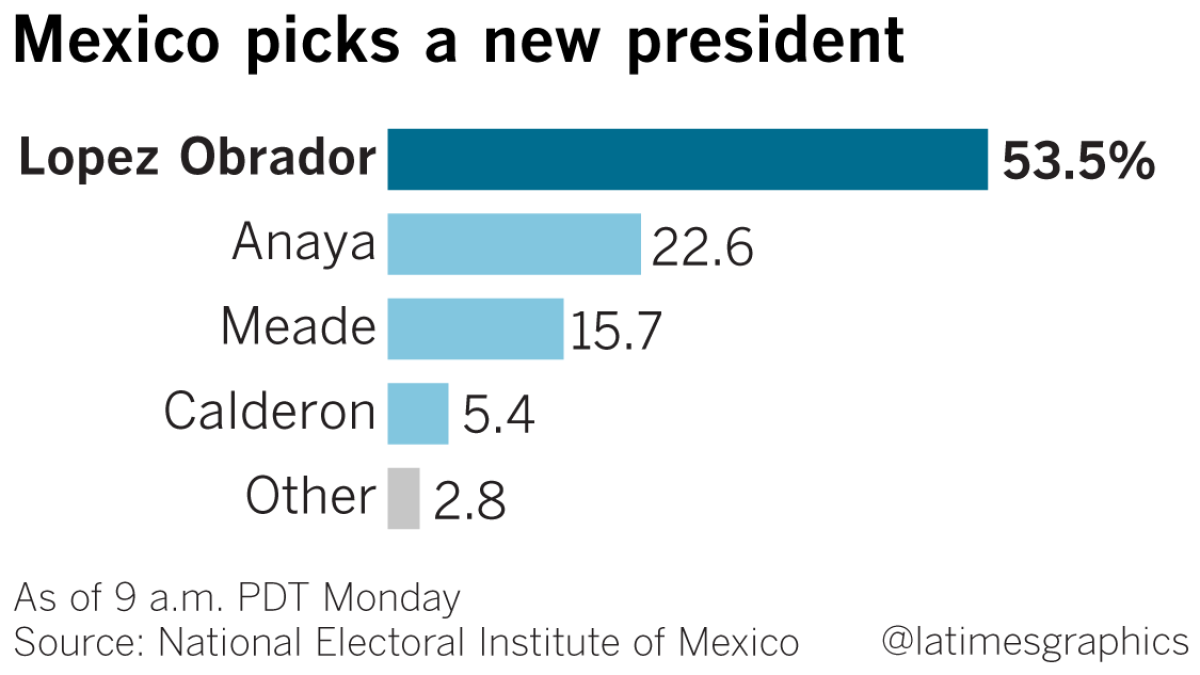

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s projected margin of victory was 31 percentage points — the largest in Mexico’s recent electoral history.

Reporting from Mexico City — Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s landslide victory in Mexico’s presidential race Sunday was not just a triumph for the left. It was also sweet redemption for a man who spent more than a dozen years running for the office.

After two losses, his self-discipline and dogged, near-constant schedule of campaigning finally paid off.

“I won’t fail you,” he told a crowd of jubilant supporters in the capital city’s central square late Sunday night, pledging to bring about “a new phase of Mexico.”

The location was highly symbolic. After his razor-thin loss in the 2006 presidential race, Lopez Obrador alleged electoral fraud and rallied his supporters in street protests that shut down the square and other parts of Mexico City for weeks.

Carlos Bravo Regidor, a professor at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching, a think tank in Mexico City, said Lopez Obrador’s victory “represents a huge vindication of his tenacity and his stubbornness” as well as his political prowess.

“He’s the most skilled popular politician that Mexican democracy has ever produced,” Bravo said.

Lopez Obrador, whom historian Enrique Krauze memorably dubbed the “Tropical Messiah” for his almost evangelical zeal and his roots in southern Mexico’s steamy Tabasco state, hasn’t held office since leaving his post as mayor of Mexico City in 2005 to run for president. Yet he has managed to keep himself in the public eye — and remain a kind of permanent candidate.

His 2006 protests may have made him seem like a sore loser in the eyes of his critics, but it also kept his base mobilized. So, too, did his years of persistent campaigning, which famously took him to every one of Mexico’s 2,464 municipal districts.

Lopez Obrador also benefited from good timing: The anti-status quo message he has been preaching for years resonated in a new way this electoral cycle. The public is fed up with corruption, rising crime and a sluggish economy, which many blame on Mexico’s traditional parties.

His victory also means Mexico’s long-suffering left, which for decades has struggled to assert itself as a force in the country’s politics, will have to adjust to being in power.

Although Lopez Obrador is a leftist on economic terms, in the past he has embraced conservative social views. In recent years, he has mostly avoided offering clear answers on issues such as same-sex marriage and abortion.

Genaro Lozano, an LGBT activist and professor of political science at Iberoamerican University, said he and others calling for a more inclusive Mexico voted for Lopez Obrador “but with a lot of doubt, a lot of uncertainties.”

During the campaign, Lopez Obrador invited into his coalition groups from across the ideological spectrum: leftist activists and intellectuals but also conservative evangelical Christians and old-time loyalists of the long-ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party — or PRI — known as the “dinosaur” generation.

Reportedly in line to be foreign minister is Hector Vasconcelos, a leftist former diplomat, classically trained pianist and son of revolutionary leader Jose Vasconcelos. Mentioned as a possible interior minister is Olga Sanchez Cordero, a left-leaning retired Supreme Court justice.

But the coalition also includes far-right former Sen. Jose Maria Martinez, who has fought abortion and same-sex marriage.

That mix could pose a challenge for Lopez Obrador.

“We’re going to see a huge civil war of people jockeying for policy priorities,” predicted Bravo, the political analyst. “This is going to make his life very difficult when it comes to governing.”

Sergio Aguayo, a journalist and academic, said Lopez Obrador’s victory is a fulfillment of the hopes of the leftist student movement of the 1960s, which were violently repressed by the military and police in the so-called Tlatelolco massacre of 1968.

“It’s the end of one cycle and the beginning of another one,” he said.

Despite his happiness about the result, Aguayo said he has doubts about how Lopez Obrador will govern given the groups from across the ideological spectrum that were invited into his winning coalition.

“He’s the best we’ve got,” Aguayo said. “But I’m prepared for the battles to come.”

Some worry whether Lopez Obrador’s only recently formed party, the National Regeneration Movement, which is known as Morena, is truly a leftist party, or just a party to serve Lopez Obrador’s interests.

For decades, the PRI managed to co-opt Mexico’s left, even as revolutionary movements swept through much of Latin America. Party leaders were extremely adept both at suppressing and incorporating emerging ideologies to preserve the party’s dominance.

The party successfully portrayed itself as the embodiment of the interests of Mexico’s working-class multitudes and as a government independent of the Cold War foreign policy of the United States. Gifts, money, public works projects and patronage jobs were key components of a successful strategy.

“We are the only option,” was one memorable slogan from that era.

But serious cracks began to appear in the PRI edifice in the late 1980s.

In 1988, Cuauhtemoc Cardenas — whose father, ex-President Lazaro Cardenas, a PRI legend, had nationalized the petroleum sector in 1938 — split from the party and ran for president on a leftist platform. He narrowly lost the 1988 election in what was widely believed to be a fraudulent vote to the PRI candidate and eventual president, Carlos Salinas de Gortari.

To this day, Lopez Obrador still regularly assails ex-President Salinas as a behind-the-scenes capo of the “mafia of power,” the clique that Lopez Obrador accuses of running Mexico. He has become the most recognizable face of Mexico’s left, sometimes to his disadvantage. During the previous campaigns and this one, business and opposition leaders compared Lopez Obrador to late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, and warned that his leftist economic policies and pledges to put “the poor first” could turn Mexico into another Venezuela.

On Monday, political scientist Denise Dresser wrote an open letter to Lopez Obrador in the Reforma newspaper, congratulating him for tapping into public anger and for correctly diagnosing Mexico’s problems, namely corruption. Change is needed, she said.

“I am not afraid that Mexico will become Venezuela,” she said. “I fear that Mexico will remain the same Mexico.”

But she professed that for all his years running for office, she still didn’t know which Lopez Obrador would show up when he is sworn in as president on Dec. 1.

“I do not know how you will govern,” she said, and “if you will be the applauded leader of a progressive left or the questionable leader of a conservative lopezobradorismo.”

Twitter: @katelinthicum

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

UPDATES:

3:40 p.m.: This article has been updated with reaction on Monday.

This article was originally posted at 3 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.