Obama’s going to a ballgame in Havana: Here’s what he needs to know about Cuban baseball

An aging wall serves as a backstop to baseball played at “the Hole” as Ismel Manzano fires a throw to second base during practice for Equipo Plaza.

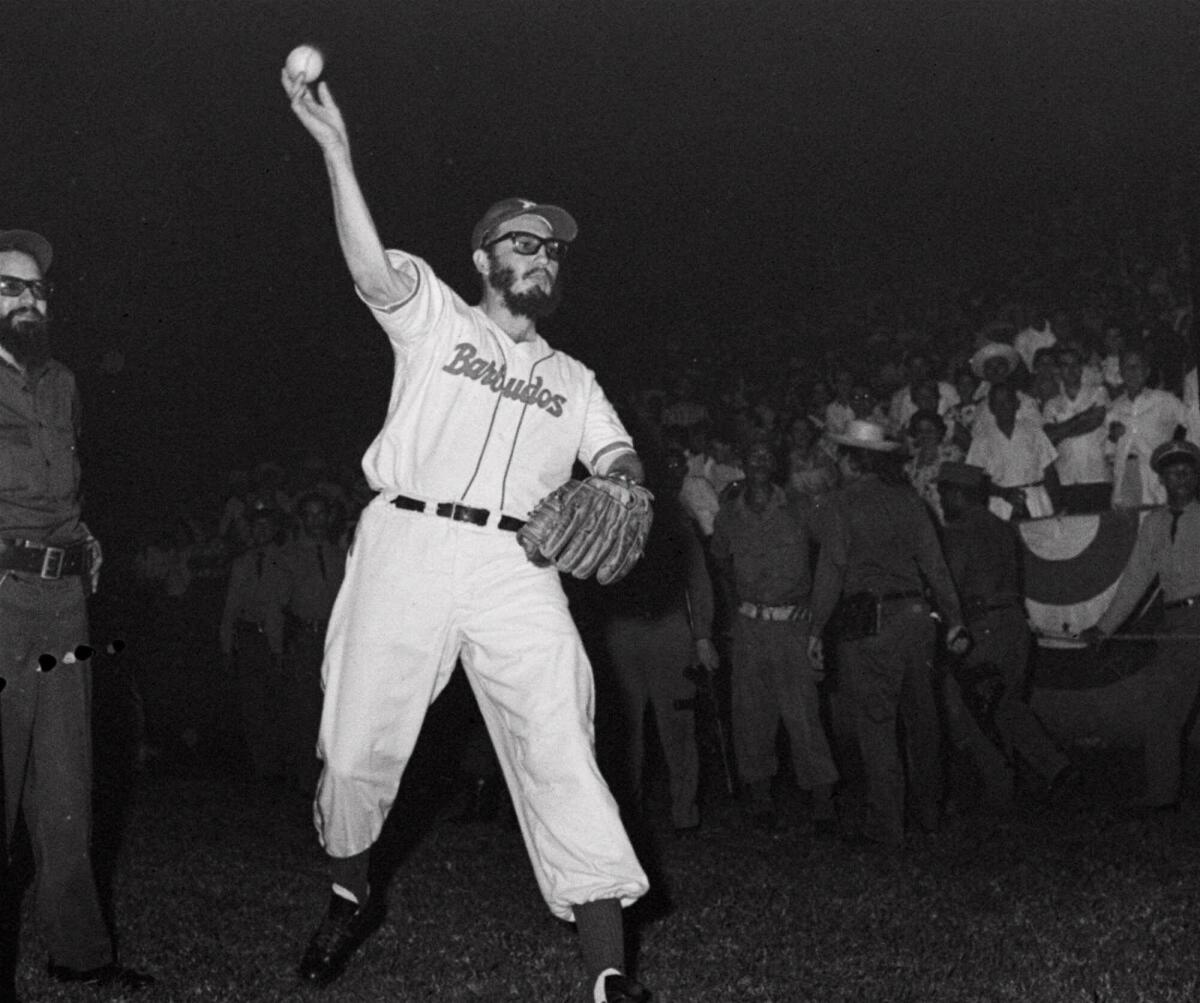

How good a baseball player was Fidel Castro?

Before turning to politics, Cuba’s revolutionary leader was said to be a right-handed pitcher with a fastball so good he was scouted by several big-league teams. Not so. Many of Castro’s biographers say the future dictator played for his high school team but wasn’t good enough to make the cut at the University of Havana, much less the major leagues.

The best Cuban player of the post-revolutionary era never to appear in a big-league game

Omar Linares was a five-tool third baseman whose baby face earned him the nickname “El Niño.” In 20 years in the domestic Serie Nacional, he set records for batting average and runs scored, slugging 404 homers and stealing 246 bases. He also led Cuba to two Olympic titles and a silver medal and was so good the Toronto Blue Jays once tried to sign him just to play in home games, which would have been allowed under Canadian law. But Linares’ loyalty was to Cuba, where he was elected to the Poder Popular, or national assembly, while still an active player. Linares’ portraits was later placed on a Cuban postage stamp.

‘The Immortal’

That nickname belongs to Martin Dihigo, who starred in Cuba, Mexico and the Negro Leagues but was banned from playing in the major leagues because of his skin color. Primarily a pitcher and second baseman, Dihigo’s best season came in 1938, when he went 18-2 with a 0.90 ERA as a pitcher in the Mexican League while winning the batting title by hitting .387. He is the only player to be inducted into baseball halls of fame in the U.S., Cuba, Mexico, Dominican Republic and Venezuela, justifying his nickname, “The Immortal.”

Baseball in Cuba is a show as much as a sport

Yasiel Puig has earned scorn from both teammates and opponents for his flamboyant play since joining the Dodgers in 2013. But he’s only playing the way he was taught in Cuba, where there are no stuffy unwritten rules to follow. Like soccer in Brazil, baseball in Cuba is played with joy and improvisation and its players are often showmen in addition to athletes. So rifling throws over the cutoff man, flipping a bat after a big home run or turning an easy defensive play into a flashy one isn’t a show of disrespect in Cuba, it’s part of the game.

Baseball isn’t just seen, it’s also heard

And we’re not talking about the pop music big-league teams play at ear-splitting volume to keep the fans awake between innings. In Cuba the fans provide their own music, with makeshift bands pounding away on drums and tin cans or tooting on trumpets and plastic horns from the first pitch to the last. Even fans without instruments contribute to the constant din, dancing in the aisles and cheering or booing spectacular and routine plays alike.

Professional baseball once flourished in Cuba

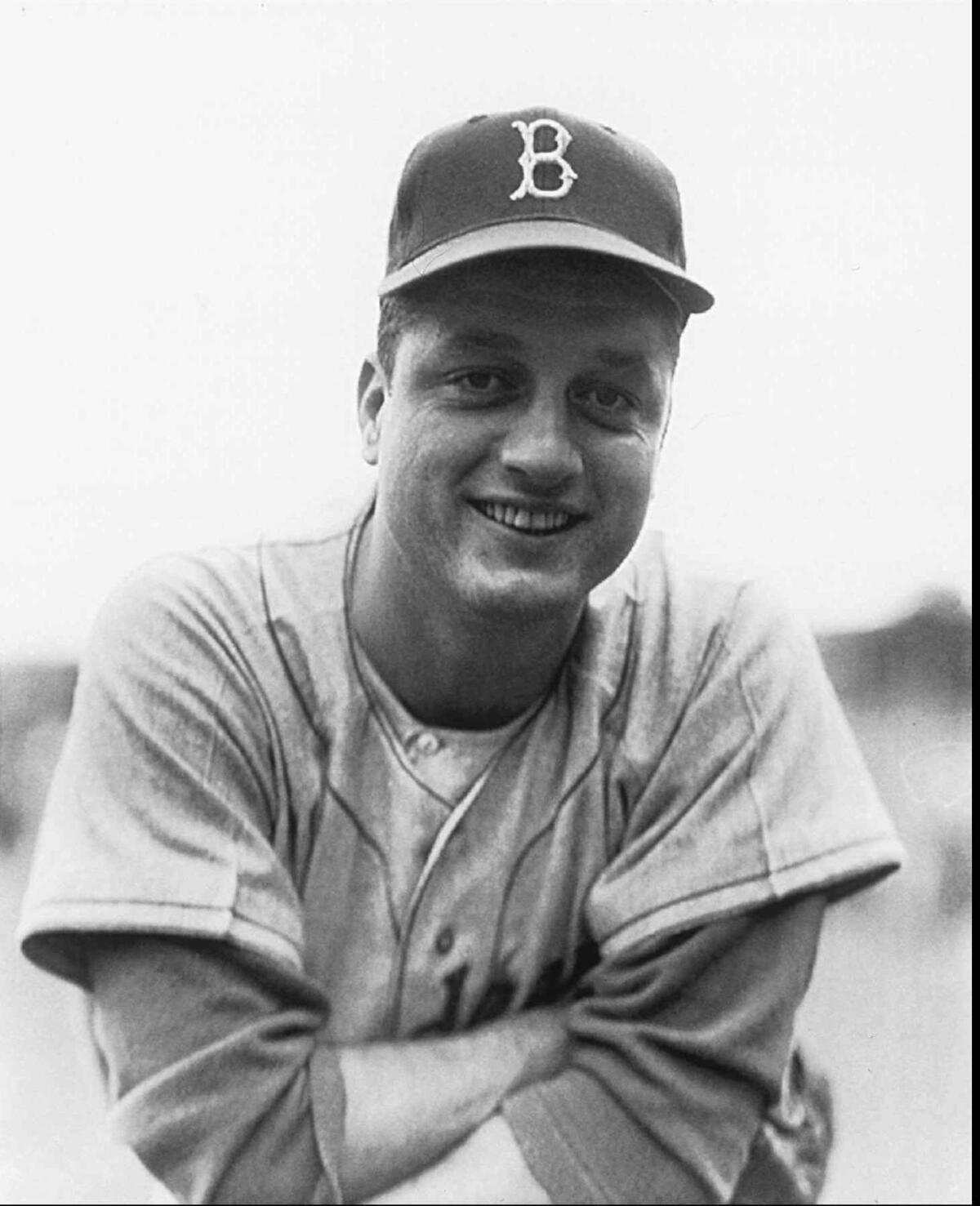

The island’s integrated winter league was a common stop for Negro League stars such as Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson and Cristobal Torriente, and later for white U.S. players including Max Lanier, Dick Sisler and a Dodgers prospect named Tommy Lasorda. But in the final 6 ½ years before Castro consolidated power and banned professional sports, Havana was also home to the Sugar Kings, a Cincinnati Reds farm team . The Sugar Kings’ success spurred talk of placing a big-league team on the island before Castro nationalized all U.S.-owned business in Cuba in 1960, driving the Sugar Kings – and major league baseball – away.

Cuba has more players in the Hall of Fame than any other country outside the U.S.

Dihigo, Jose Mendez and Torriente were all inducted into Cooperstown based on their exploits during the Negro League era. The fourth player, Tony Perez, signed in 1960 and was one of the last professionals allowed to leave the island legally. He played 23 seasons in the majors with four teams.

If not for the Cuban revolution, Dominican Republic ballplayers may have gone unnoticed

By the time Castro came to power in 1959, Cuba had sent 77 players to the big leagues – or 76 more than had been signed out of the Dominican. But when the Castro revolution shut off the pipeline of cheap talent from Cuba to the major leagues, the focus shifted to the Dominican Republic. Since then 640 Dominicans have played in the majors, every U.S. team has established an elaborate training academy on the island and baseball has joined sugar and tourism as a major contributor to the country’s economy.

It pays to defect

In 2014 the Cuban government approved six categories of salary hikes that will pay baseball players between $18 and $60 a month, plus bonuses. Which is why players ride bicycles and public buses to games. In the U.S., 10 Cuban defectors earned at least $5 million each last season. Which is why Yasiel Puig can afford to take a helicopter to games.

“Fidel from Havana, go ahead….”

Forget sports-talk radio.

If President Obama really wants to find out what Cubans think he’ll have to stop by the Esquina Caliente or Hot Corner in Havana’s Parque Central, where dozens of fans gather every afternoon for loud, passionate and educated discussions about baseball.

In the past, Cuban baseball dominated the debates. But with so many Cubans playing in the U.S., the major leagues have become a common part of the discussions as well.

ALSO

Obama arrives in Cuba for historic trip, but the Cuban government signals it is standing firm

Video: Guava pastries and other suggestions for Obama's busy schedule

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.