Brazil’s Senate votes to remove president Dilma Rousseff from power

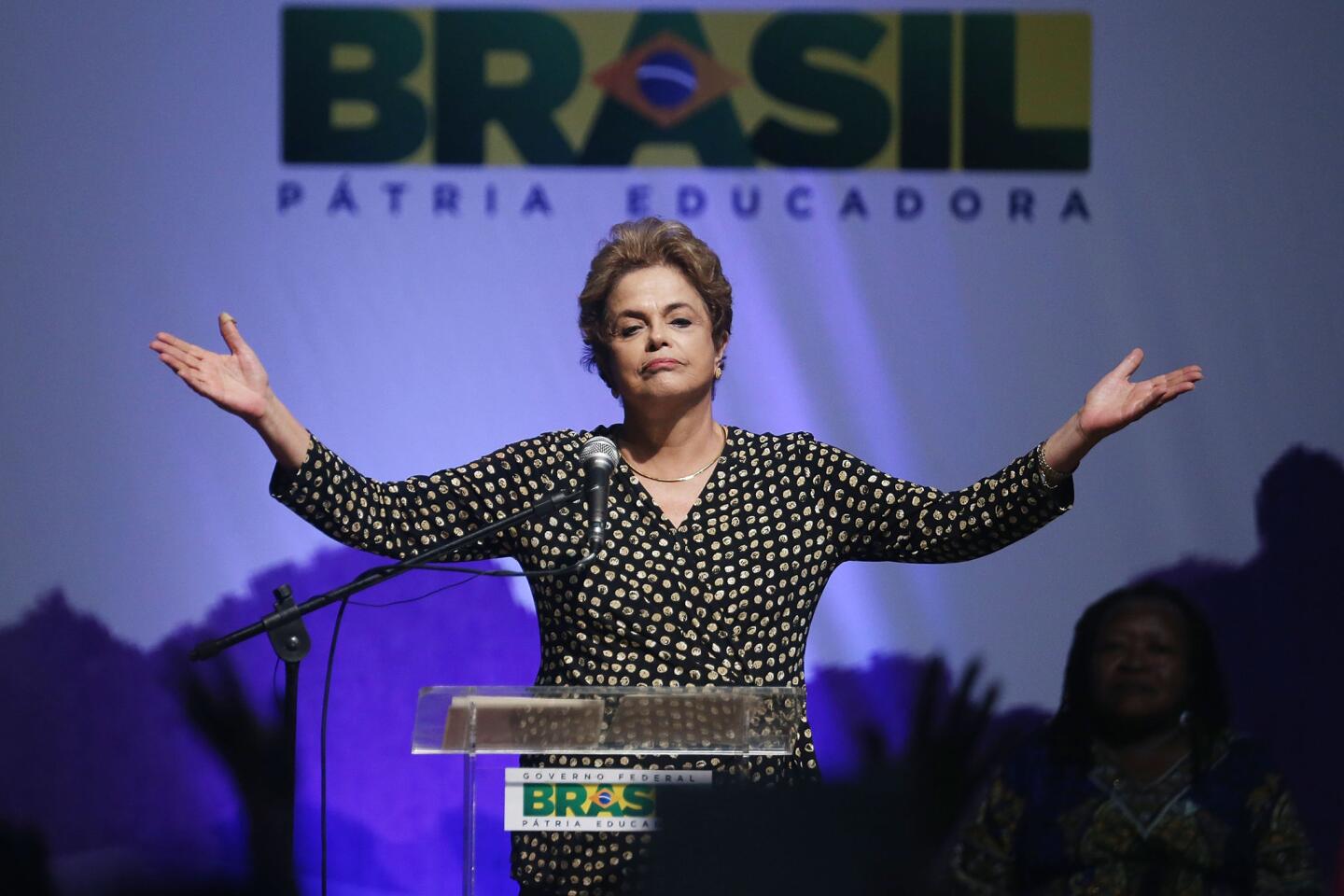

Brazil’s suspended President Dilma Rousseff makes a statement at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia on May 12, 2016.

Reporting from Sao Paulo, Brazil — Brazil’s Senate has voted to remove leftist President Dilma Rousseff from power and subject her to an impeachment trial, effectively handing the government over to an unpopular coalition of more conservative forces that will face an economic crisis as well as accusations they have seized power illegitimately.

Rousseff, who will be tried on charges of misleading fiscal accounting, technically would be removed only for 180 days as the Senate decides on permanent removal, but former ally Vice President Michel Temer has treated his ascendance as a fait accompli, publicly assembling a new Cabinet and planning to move the world’s fifth most populous country in a more market-friendly direction.

Until recently considered a model for economic growth and social progress, Latin America’s largest country is now facing its worst recession in decades, a multibillion-dollar corruption scandal, a health crisis caused by the Zika virus, and the prospect of hosting the Rio Olympics in August without a stable government in place.

“Our challenges are certainly the greatest that Brazil has ever seen,” said Sen. Marta Suplicy, who served as Rousseff’s minister of culture before leaving the Workers’ Party for Temer’s center-right PMDB party last year.

But as Suplicy explained her vote to impeach, she said, “I trust we can build a broad base of political and social support, of workers and businesses, to create a united government.”

Demonstrations both for and against impeachment have been constant all week across Brazil, and continued into Wednesday. While opponents of Rousseff prepared to celebrate, some left-wing groups have said they refuse to accept a Temer government.

Rousseff is a former left-wing guerrilla turned economist who was hailed as a technocratic reformer when she took over for Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva in 2010 as the country’s first female president, and she enjoyed widespread popularity until the economy fell into a deep recession.

The deeply unpopular Rousseff already had lost a round in the lower house of Congress, the Chamber of Deputies, where a two-thirds vote was required to advance the impeachment process. On Wednesday, only a simple majority of 41 votes was needed.

Under law, Rousseff would be relieved of duties as soon as she is informed of the decision, which is expected to take place Thursday.

She has not been personally accused of any corruption or criminal offense, and will hand the reins over to men who do face accusations. She has fought the process tooth and nail, appealing to the international community to stop a right-wing “coup” against her, but even Lula, who first took office in 2003, has admitted it would be very difficult to restore Rousseff to power after a loss Wednesday.

The Senate proceedings, conducted in a somber manner in the capital of Brasilia, followed a sometimes raucous and overwhelmingly anti-Rousseff vote weeks earlier in the Chamber of Deputies.

The labyrinthine process has been bitterly contested and widely criticized in Brazil and abroad since it began in December.

A number of South American governments have strongly criticized the impeachment, and the secretary-general of the Organization of American States has said he will take the case to a regional human rights court. Temer is likely to seek legitimization from the Obama administration, while some on Brazil’s left have demanded that the U.S. denounce the change of power.

“Brazil is so dominant in the region that it’s in everyone’s best interests to try put conflicts behind them and work with a [post-impeachment] government. But this is a big defeat for the left in Latin America,” says Peter Hakim, president emeritus at the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank. “I think the U.S. is going to try to stand aside, knowing that either position they take could be rebound badly and be counterproductive.”

As much of South America moved to the left in the 21st century, Brazil maintained good relations with more radical countries, such as Venezuela and Bolivia, as well as more conservative neighbors and the U.S., all the while earning international plaudits for stable democracy and economic growth that lifted tens of millions out of poverty.

The high point of this meteoric rise may have been when Rio beat out a President Obama-backed Chicago to host the 2016 Olympics. Two years ago, the soccer-mad country hosted the World Cup.

But now countries in the region are divided on whether to view the Temer government as legitimate or the result of a so-called “soft coup,” which only has the appearance of institutional integrity, lumping scandal-racked Brazil in with countries like Paraguay and Honduras, both of which suffered non-military putsches in the last decade.

As it became clear earlier this year that Rousseff’s government might fall, Brazil’s Constitution offered a number of ways she might be removed. Brazil’s more traditional political parties united behind the one tactic that would allow them to take power immediately without having to face elections.

Congress members, most of whom face criminal investigations themselves for possible corruption or other serious crimes, set aside questions of corruption for the impeachment process, focusing instead on relatively minor accounting maneuvers used to formulate the national budget. (Opponents of impeachment note Temer himself had OK’ed such maneuvers.)

As Rousseff’s opponents pushed forward, the case took a staggering number of strange turns, leaving the population confused and exasperated as the impeachment question often devolved into political shouting matches.

“This case has been the real-life version of a Kafka novel. It’s like ‘The Trial,’” said Francisco Fonseca, a political scientist at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas business school in Sao Paulo. “They have attempted to remove Rousseff and her party with whatever mechanism or argument they can muster.”

Polls show only 2% of Brazilians would vote for Temer in a general vote, while roughly 60% of Brazilians want both Rousseff and Temer impeached.

Brazil’s political scene had already been thrown into chaos as the federal police’s Lava Jato, or Car Wash, investigation implicated much of Brazil’s political and business elite in corruption. Crusading Car Wash investigators revealed a staggering bribery scheme at Petrobras, the country’s state-run oil company, which has implicated high-ranking members of Rousseff’s party.

Many political analysts argue, however, that the true cause of Rousseff’s removal was her failure to maintain support in Congress as regular Brazilians turned on her due to rising unemployment and inflation.

“We need to get her out, but we need to get the rest of the politicians out, too. The new guys won’t be better than her,” said Jose Ferreira, 56, who says he regrets voting for Rousseff twice and works delivering groceries in the town where Lula launched his political career.

Ferreira said he has watched families able to afford less and less as prices rise and incomes stagnate. “She wasn’t so bad in the first term, but when she ran for reelection we had no idea it would get this bad.”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.