‘El Chapo’ witness, a former Chicago drug boss, starts tying the pieces together for jurors

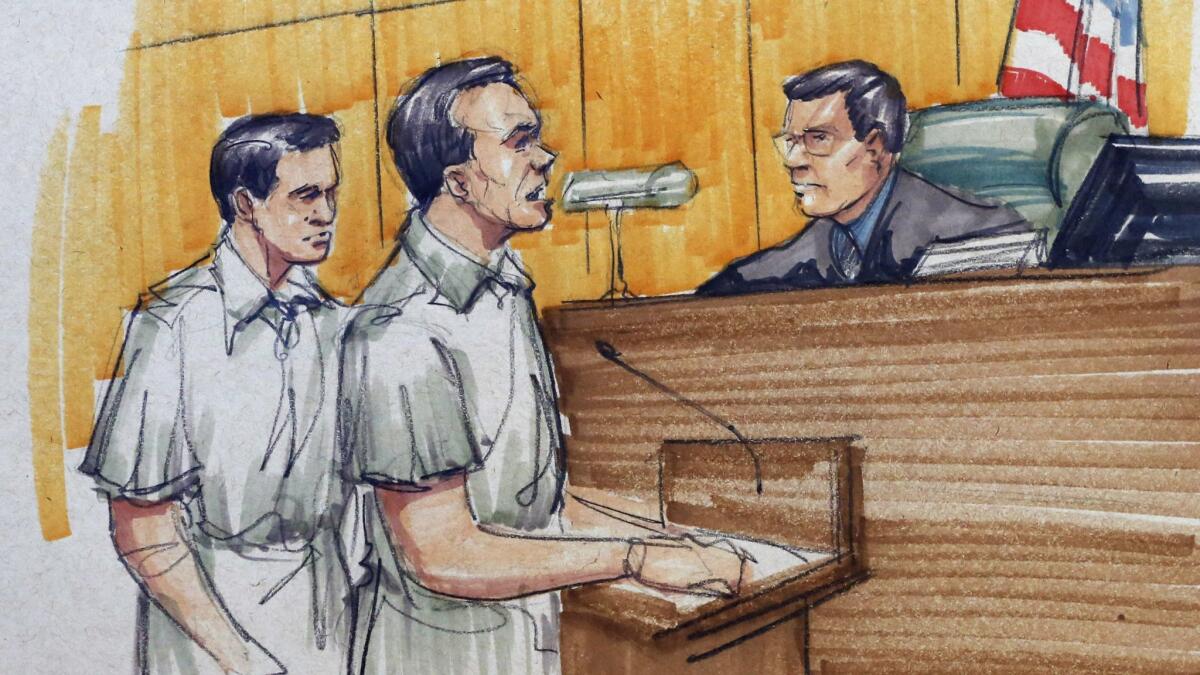

Reporting from New York — Chicago drug boss turned career informant Pedro Flores left jurors hanging for more than an hour after he was first called to testify against Mexican drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman on Tuesday — so long that Judge Brian Cogan dismissed court for lunch to await his arrival.

The morning had devolved into tedious bickering between defense attorney Jeffrey Lichtman and former Colombian narco Jorge Cifuentes, and the upcoming Christmas break shimmered on the horizon. But from the moment he appeared on the stand, it was clear Flores had jurors’ full attention.

Though they hadn’t known it before, this was the man jurors had been waiting to meet since the start of the trial.

“I had this idea about how it would be, like in the movies,” Flores recalled telling Guzman of their first meeting in the mountains of Sinaloa in 2005. “Like you’re just lining people up and shooting them one after the next.”

The drug boss laughed.

“In a serious tone he told me, ‘Only the ones we have to,’” Flores said.

Flores and his twin brother, Margarito, ran one of the largest drug trafficking operations in the United States, importing and distributing close to 40 tons of cocaine and 200 kilos of heroin through Chicago for the Sinaloa cartel. He told the court he’d started in the drug trade as a grade schooler. Yet compared with his predecessors on the witness stand, his significance to the trial — at which Guzman faces charges of drug trafficking, conspiracy to murder and firearms violations — is harder to see at first glance.

Flores didn’t know Guzman closely — he had to be coached to refer to the defendant as anything other than “the man” — and never ordered any killings, as previous witnesses have confessed. The most gruesome detail he shared on Tuesday was about a naked man he saw chained to a tree at Guzman’s secret hideaway in the mountains, the closest thing to an intimacy a pair of jean shorts he presented to the boss as a gag gift after Guzman ribbed him for wearing a similar pair on their first meeting.

But like Chicago, the city whose drugs he ran for a decade, Flores was “halfway to everywhere” in Guzman’s drug empire. In the manner of a double agent unveiling the twist at the climax of a John le Carre novel, he quietly but methodically connected the dots left behind by the witnesses who preceded him. Coincidences were unmasked, tangles of dangling details spun into a single, damning narrative.

Flores recalled driving the same battered tan “kidnapper van” from the same Denny’s on the outskirts of Chicago to the same ill-fated warehouse that a retired narcotics detective from the Chicago Police Department testified about Thursday.

“The bags began to rip and the kilos were falling out — it was a pretty hectic day,” Flores said of his work there, just months before the stash house was busted and the detective discovered nearly 2,000 kilos of cocaine. The name of Flores’ handler was the same name the detective said was printed on the bricks of coke.

When Flores went to meet Guzman, it was in the same plane from the same Culiacan, Mexico, cornfield that Cifuentes said he took. They landed at the same inclined runway, over which Cifuentes said he prayed three Our Fathers when he saw it from the air. Even the hand motions they used to describe the gradient were identical.

Every word from the informant’s mouth seemed to verify something another witness had said. Dozens of names that had been all but meaningless before suddenly had roles, personalities, even faces. Deaths that had been listed, matter of fact, became menacing. Drug seizures law enforcement officials had dryly described were suffused with drama, as Flores outlined for the jury their grave consequences for traffickers like him.

Flores told of being kidnapped, held for two weeks and driven into the wilderness for what he believed to be his execution over missing cocaine. “Whoever lost it is going to pay,” the witness recalled his former boss, Lupe Ledesma, telling him just before Flores was taken.

“At that point, I felt it wasn’t even worth it for me to beg for my life,” Flores recalled.

But Guzman interceded to save him and later ordered Ledesma killed, the witness said.

“They’re seeing ghosts,” Flores said Guzman told him when he relayed a rumor about Ledesma. “Worry about something else.”

Flores said it was only when his wife got pregnant that he decided he’d had enough of the Sinaloa cartel. He and his brother started feeding the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration information in late 2008.

“Me and my brother were born while my father was in prison,” Flores, who is serving time in a federal prison, told the jury. “I wanted something better for my children.”

His other incentive? Internecine war between Guzman and his partner Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada and their longtime colleagues turned rivals, the Beltran Leyvas, who each insisted that the Flores twins pledge loyalty to them and forswear their competitor.

“For years, my brother and I had enjoyed a sweet spot in the cartel; we didn’t have to worry about any of this stuff,” he told jurors. “If we were going to continue to risk our lives, we were going to do it trying to get out.”

Sharp is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.