The big loser in Ukraine’s presidential election? Vladimir Putin

Reporting from KIEV, Ukraine — Russian President Vladimir Putin wasn’t running in the Ukrainian presidential election. But he was by far the biggest loser of the night.

Only one of the 39 candidates on the ballot Sunday promoted the idea of closer ties with Russia. He received less than 12% of the vote.

When the Kremlin annexed Crimea in 2014 and sent troops to support pro-Russian separatist rebels in eastern Ukraine, Putin inadvertently built a stronger Ukraine. Before then, it was a country divided along fault lines of languages and geography. Today, the post-Soviet nation of 43 million is united around a common national identity.

And that identity is firmly pro-independent Ukraine and anti-Putin.

If Sunday’s vote is any indication — and, by most accounts, it is — Ukraine has firmly turned its back on Moscow and turned to fully embrace European-style democracy.

“After what happened in 2014, the support in Ukraine for joining a Eurasian coalition with Russia totally collapsed,” said Oleksiy Haran, research director of the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, based in Kiev.

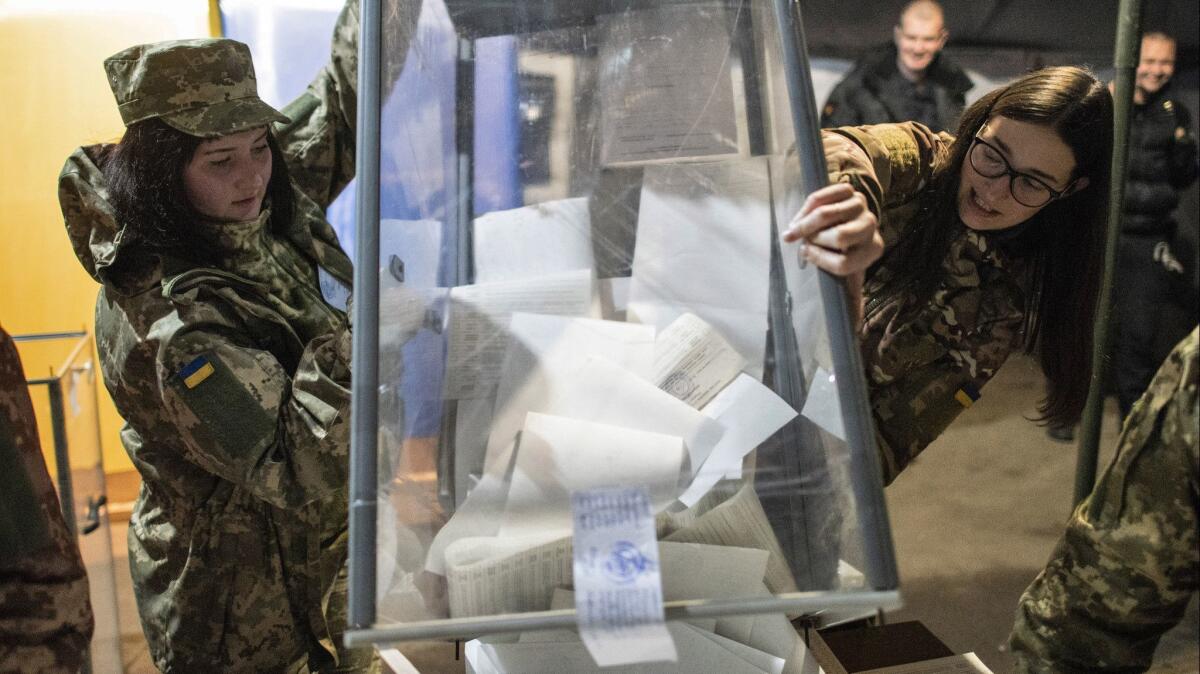

Despite the war in the east and staggered economic growth, Ukraine successfully held a free and fair election Sunday, with the most competitive ballot list in its history.

Nearly a third of Ukrainian voters cast their ballots for Volodymyr Zelensky, a 41-year-old comedian who ran as an anti-establishment candidate with a Western-focused platform. The political novice reeled in voters with promises to change Ukraine’s corrupted, oligarch-entrenched political system.

His supporters said he would be a new face to replace Ukraine’s old guard political elite.

Zelensky will face off on April 21 with President Petro Poroshenko, who had 16% of the vote. The 53-year-old confectionery tycoon and one of the country’s richest men has overseen the country’s war in the east; his campaign was built around the slogan “Language. Faith. Army.”

Sunday night, Ukrainians reveled in the fact that their suspenseful and unpredictable race stood in stark contrast to campaigns in Russia, where voters last year reelected Putin for a fourth term with no real opposition allowed on the ballot.

“OK, sure our election is kind of crazy with all these guys on the ballot, and some of them aren’t even doing a real campaign,” said Ihor Piskovoy, 34, a teacher in Kiev. “But at least we have a choice. They don’t have that in Russia.”

“Putin had an extremely stupid plan in 2014 to create turmoil in southeast Ukraine,” said Kostiantyn Fedorenko, a political analyst with the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation, a think thank in Kiev. “Ukrainians changed their mentality significantly after it became clear that Russia could use military power against Ukraine.”

Pompeo firmly opposes Russian claims on Crimea and Ukraine, but struggles to explain Trump »

Ivona Kostyna, who runs the Veteran Hub, a nonprofit that helps veterans of the war against Russian-backed forces in eastern Ukraine, went so far as to say that the war with Russia had been good for Ukraine because it had helped solidify a sense of national purpose.

“War is never a good thing, of course,” she said in an interview in her organization’s light-splashed offices in Kiev, where veterans milled about amid the smell of brewing coffee. “People killing people is a quite damaging thing for society.”

But the twin crises of the Maidan uprising, when Ukrainians banded together to overthrow a president who rejected an association agreement with the European Union, and the war in eastern Ukraine, changed the national attitude, she said.

“When the war started … people actually united under the only value they all shared, which is Ukrainian territorial integrity, independence and … our safety and ability to actually make choices.”

That was “mind-changing,” she said. And military conscription brought together Ukrainians of all kinds, often for the first time. “It was interesting to see how these people reacted and how they formed new communities.”

“To this extent, I think the war made us realize that we’re the only people who can do something good for ourselves.”

She wasn’t thrilled with the results of the election, she said, but what was important was that it was democratic.

“The right to make a choice is worth fighting for,” she said.

After exit poll figures were released Sunday night, Zelensky and Poroshenko immediately started attacking each other.

Poroshenko on Monday morning hinted at what was expected to be a strategy to make Zelensky appear to be unpatriotic, with possible ties to Russia’s political and cultural elite.

In a campaign meme on social media, the Poroshenko campaign showed an image of Maidan protesters waving Ukraine’s blue and yellow flags with the slogan “Ukrainians put the Russian scenario to bed in the first round. I know they’ll do it in the second, too.”

Zelensky’s camp said they had plans to combat Poroshenko’s attacks. The candidate’s digital campaign manager, Mikhail Federov, told journalists: “We are going to destroy him.”

Zelensky stars in a sitcom about a history teacher who accidentally becomes president and goes up against the political elite.

The popular actor received strong support in the east and southeast, where turnout was close to the national average of 63%. Before 2014, those regions leaned toward closer Russian ties. The western and central parts of the country looked westward.

But after war started in the southeastern Donbas region, more residents there began to identify themselves as Ukrainian and saw their future in a Western-style democracy far from Moscow’s purview, Fedorenko said.

“These election results in these regions prove that Maidan and the Donbas war have been a success in constructing a unified Ukraine,” Fedorenko said.

One issue that has been used as a political wedge for decades in Ukraine — a bilingual nation — is language.

During the time of the Soviet Union, the dominant language was Russian, as it was across the republics. Since independence, the Ukrainian language has become more frequently used and has been promoted in schools and government offices. Russian is more prevalent in the southeast.

Politicians have long used language laws that restrict or promote one or the other as a way to garner votes.

Poroshenko has taken a strong stance on the Ukrainian language, blocking popular Russian social media and websites, and promoting controversial Ukrainian nationalists as state heroes. Zelensky’s inclusive stance on language and Ukrainian history has appealed to southeastern voters.

Zelensky isn’t shy about being a Russian speaker, although he can — and does — speak Ukrainian. He has said he supports Ukrainian as the state language, but hasn’t made language laws part of his campaign. Voters in the southeast, many of whom speak Russian as their first language, have liked that, Fedorenko said.

Poroshenko will have an uphill battle to close the polling gap by April 21. The key could be winning over those southeastern voters, newfound Ukrainian patriots close to the front who want to see an end to the war.

Ayres is a special correspondent. Times foreign editor Mitchell Landsberg contributed to this report. Reporting for this article was partially funded by KfW Development Bank, which supports nonpartisan, nonprofit German Marshall Fund of the United States fellowships.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.