What were they thinking? 5 decisions that made the Nobel Prizes look bad

Reporting from STOCKHOLM — Scientists who created tiny molecular machines and illuminated the properties of exotic states of matter were among those honored with Nobel Prizes this year.

The prizes cannot be revoked, so the judges must put a lot of thought into their selections for the six awards.

A discovery might seem groundbreaking today, but will it stand the test of time?

Prize founder Alfred Nobel wanted to honor those whose discoveries created “the greatest benefit to mankind.” Here are five Nobel Prize decisions that, in hindsight, seem questionable:

When a German who organized poison gas attacks won the chemistry prize

Fritz Haber was awarded the 1918 chemistry award for discovering how to create ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen gases. His method was used to manufacture fertilizers and delivered a major boost to agriculture worldwide.

But the Nobel committee completely overlooked Haber’s role in chemical warfare during World War I. Enthusiastically supporting the German war effort, he supervised the first major chlorine gas attack at Ypres, Belgium, in 1915, which killed thousands of Allied troops.

When the medicine committee awarded a cancer discovery that wasn’t

Danish scientist Johannes Fibiger won the 1926 medicine award for discovering that a roundworm caused cancer in rats.

There was only one problem: The roundworm didn’t cause cancer in rats.

Fibiger insisted his research showed that rats ingesting worm larvae by eating cockroaches developed cancer. At the time he won the prize, the Nobel judges thought that made perfect sense.

It later turned out the rats developed cancer from a lack of vitamin A.

Oops.

When the chemistry prize honored a man who found use for DDT, which was later banned

The 1948 medicine prize to Swiss scientist Paul Mueller honored a discovery that ended up doing both good and bad.

Mueller didn’t invent dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, but he discovered that it was a powerful pesticide that could kill lots of flies, mosquitoes and beetles in a short time.

The compound proved very effective in protecting agricultural crops and fighting insect-borne diseases such as typhus and malaria. DDT saved hundreds of thousands of lives and helped eradicate malaria from southern Europe.

But in the 1960s environmentalists found that DDT was poisoning wildlife and the environment. The U.S. banned DDT in 1972, and in 2001 it was banned by an international treaty, though exemptions are allowed for some countries fighting malaria.

When the man who invented lobotomy won the medicine prize

Carving up people’s brains may have seemed like a good idea at the time. But in hindsight, rewarding Portuguese scientist Antonio Egas Moniz in 1949 for inventing lobotomy to treat mental illness wasn’t the Nobel Prizes’ finest hour.

The method became very popular in the 1940s, and at the award ceremony it was praised as “one of the most important discoveries ever made in psychiatric therapy.”

But it had serious side effects: Some patients died and others were left severely brain damaged. Even operations that were considered successful left patients unresponsive and emotionally numb.

The method declined quickly in the 1950s as drugs to treat mental illness became widespread, and it’s very seldom used today.

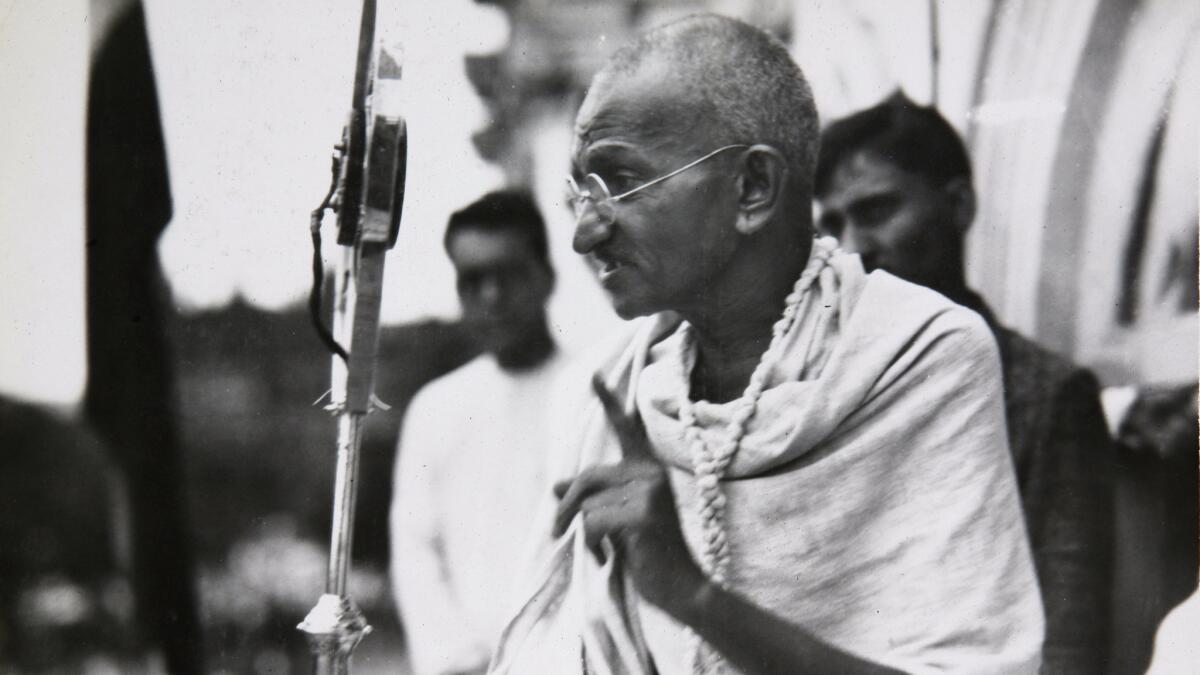

When India’s Mohandas K. Gandhi didn’t win the peace prize

The Indian independence leader, considered one of history’s great champions of nonviolent struggle, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize no fewer than five times. He never won.

The peace prize committee, which rarely concedes a mistake, eventually acknowledged that not awarding Gandhi was an omission.

In 1989 — 41 years after Gandhi’s death — the Nobel committee chairman paid tribute to Gandhi as he presented that year’s award to the Dalai Lama.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.