‘Girls in India just aren’t safe’

A woman in New Delhi speaks of a life lived in fear after the December gang rape and fatal beating of a 23-year-old on a commuter bus.

When she was a girl growing up in India's mountainous northeast, Sobhana Gazmer used to rough up boys who gave her lip. These days in the big city of New Delhi, she's scared to walk the streets, take public transportation, even sleep in her one-room apartment, with its single bed covered in stuffed animals.

Her apartment is a few hundred feet from the stop where a commuter bus picked up a young woman whose fate haunts Gazmer: She was raped repeatedly, allegedly by the driver and his friends, and then assaulted along with her male friend with metal rods. She died of her injuries two weeks later.

Rape cases have been a fixture in India's headlines for years, but the brutal attack in December hit a deep nerve. Many young women saw themselves in the victim, a 23-year-old physiotherapy student of modest means who moved to New Delhi to chase the Indian dream — and gain independence in the process.

"No matter how strong we want to be, how bold, with women power, if there are two or three guys, you just have to turn and run," said Gazmer, 29. "Since December, I hardly go out, even with friends. That could've been me. Every woman thinks that way."

Gazmer is an outgoing professional with an easy laugh who works nights in a call center in New Delhi answering credit card questions for Americans. She makes more money than her soldier father or teacher mother, and dreams of eventually starting her own business.

But her parallels with the victim of the bus attack don't stop with aspirations for a better life.

A year after landing an earlier call-center job in 2009 and renting her own apartment, she headed out to a shopping area early one evening with a male friend. As they hailed a tuk-tuk, she was attacked by several men: initially three in their early 20s, and two more who then joined in. They were intent on forcing her into a car and raping her, she said.

Sobhana Gazmer, 29, who works at a call center in the New Delhi area answering calls from Americans about their credit card accounts, feels increasingly anxious since a high-profile rape in mid-December sent shock waves through the country. (Mark Magnier / Los Angeles Times) More photos

That could've been me. Every woman thinks that way."— Sobhana Gazmer

Because she had only recently moved to the city, she said, she was so naive that she called them brother — a sign of respect — and asked them what they wanted, which only made them more aggressive.

In a bid to drag Gazmer into the car, the attackers started beating her. Dozens of pedestrians walked by, some even stopping to watch, but no one helped, she recalled, something unthinkable in her hometown.

"In Manipur, if any guy bothers you, you shout and everyone helps," she said. "In Delhi, it's a very different mentality — you have to think for yourself. And women are stronger in Manipur. We don't take it."

Gazmer's male friend tried to defend her, distracting them. Sensing an opening, she took off her sandals and ran barefoot the several hundred yards back to her apartment. Terrified, she locked her two gates and the door behind her, then sat shaking on her bed, wondering what to do about her friend.

After an hour, he called and praised her for her quick thinking in running away. I can save myself, he told her, but both of us couldn't have saved you. He said he had tried to defend himself against one of the men only to have others attack him from behind. They smashed his face, fractured a rib and pounded his stomach. Gazmer called the police, but they never came, she said, so they took themselves to the hospital.

Every few days, Gazmer said, her mother calls, pressuring her to leave "dangerous Delhi," find a husband, settle down in Manipur. She resists.

"There's no good job in Manipur, no electricity," she said. "It's emotional blackmail. Marriage, marriage, marriage. Sometimes when she calls, I just put the phone on 'silent' knowing what she's going to say."

Gazmer, the youngest of four sisters, particularly enjoys the independence of earning her own money and buying what she wants without the second-guessing that often comes in close Indian families. Whenever she goes home for a visit, she's happy for a couple of days, then gets bored.

"I love the freedom of my life," she said. "This is the big city."

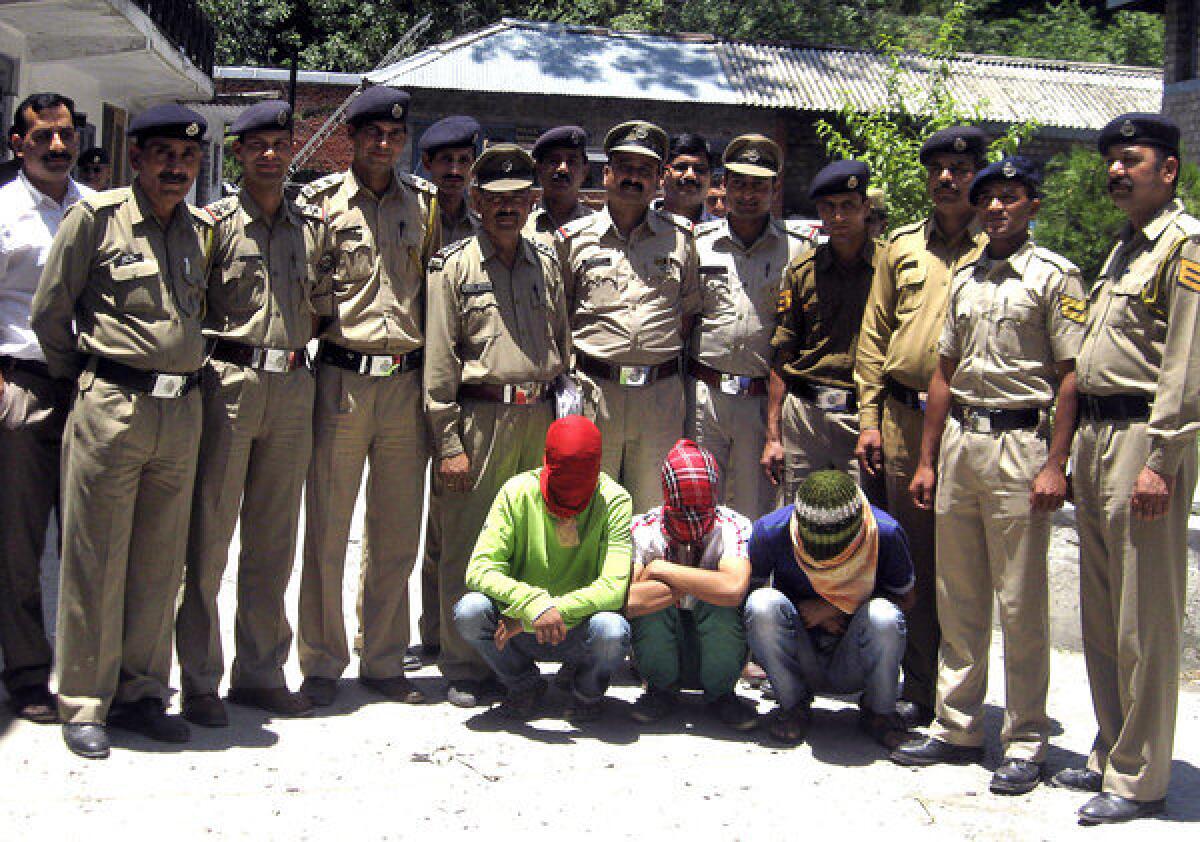

Indian police stand with three hooded men suspected in the gang-rape of an American woman in Manali this month. (Associated Press) More photos

But that freedom comes at a price: Her apartment is at the top of a four-floor walk-up so close to the next building you can jump to its adjoining balcony, which is exactly what some drunk guys did a few months back on a lower floor.

Since then, the landlord has beefed up security, adding closed-circuit cameras and electronic gates, the building's exposed pipes, chipped paint and dirty floors contrasting with the modern devices.

Speaking to Americans for hours each night on the phone — many call centers don't volunteer that they're in India and Gazmer's pseudonym is Sonia Smith — has opened her mind, she said. Although some people on the other end express anger, saying Indians are stealing American jobs, most are friendly and quite generous, she said, even telling her she sounds pretty and must have many boyfriends.

"A friend told me: In the U.S., you smile and act friendly," she said. "But here, you have to hold everything inside; there's no frankness or guys will get the wrong idea."

On paper, Indian rape statistics are lower than in many Western countries, but experts say a large number of the assaults go unreported. A United Nations report in November 2012 found just 5% of women and girls considered New Delhi streets safe from sexual violence. India is ranked 129 out of 147 countries on the U.N.'s Gender Equality Index, behind Bangladesh and Rwanda.

The brutal December attack left psychological damage and anxiety nationwide in a society where women suffer near-daily snickers, pawing and threats that can make them feel like prey.

"Police don't care, bureaucrats are indifferent, politicians find women seductive — it's the entire regime," said Shiv Visvanathan, a sociology professor at the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy in Sonipat, just north of New Delhi. "Women suffer numerous indignities, are harassed, attacked. There's the psychological impact, embarrassment, even being disowned by their families."

Indian women hold a march for dignity in New Delhi in January. (Prakash Singh / AFP/Getty Images) More photos

Few women express confidence in Indian police, and many say they've adopted new strategies to protect themselves. Since December, sales of pepper spray and issuance of gun licenses to women have soared, and many women say they keep in near-hourly contact with their parents and text the license plate of buses or taxis before boarding. New one-touch apps for women summon help using a cellphone's GPS.

After the December rape, Gazmer's company offered to switch her to the day shift, but that schedule doesn't allow two consecutive days off, so she turned down the offer.

The taxi van hired by the company to pick up and drop off workers has rules precluding women from being the first or last in the van so the driver doesn't try something, although occasionally they still do, Gazmer said. And she never knows when her van will arrive. Waiting even a few minutes by the curb attracts leers, insults and drivers who stop and proposition her, offer her a ride, tell her, "I'll take you wherever you're going, baby."

"It's always in my mind," she said. "I'm scared just leaving my house."

Since the December attack, she doesn't go out except when it's absolutely essential, even with male friends, and has dialed down her social life to near zero. That means long hours spent in her apartment, where a Santa cutout hangs forgotten on the wall near a noisy fan and a mirror is attached to the wall with duct tape.

She used to attend parties occasionally on her days off but has given that up and is always careful to be home soon after dark. She's started dressing more conservatively, limiting sleeveless shirts and shorts to the relative refuge of the office.

She's also studied a bit of self-defense. A few months ago she was catching a taxi with a girlfriend when a man came by and rubbed up against her even though there was lots of space. In a loud voice she asked him if she should call the police and, irate despite her fear, was about to slap him before her friend pulled her away.

Demonstrators in New Delhi in January call for justice in recent rape cases in India. (Altaf Qadri / Associated Press) More photos

"In my hometown, I would've beaten up the guy," she said. "But in Delhi, you have to be a lot more careful."

But her fighting spirit hasn't totally abandoned her. Recently on a crowded bus, a man kept touching her. She took out a safety pin and jammed it into him, watching with satisfaction at his pained, shocked look as he retreated.

In response to the public outcry after the gang rape, new laws have increased the punishment for rape, gang rape, stalking and other sex-related crimes. Gazmer said she's not sure even capital punishment is a deterrent and believes those caught should be publicly beaten and humiliated. Too many guilty people in India bribe or use political connections, she said, serving only token jail sentences.

"Some good punishment must be there, or things won't change," she said. "Girls in India just aren't safe."

Tanvi Sharma in The Times' New Delhi bureau contributed to this report.

Follow Mark Magnier (@markmagnier) on Twitter

More great reads

Ensuring the Tenderloin's departed are not forgotten

Grief, as I often say to others, is just the price we pay for love."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.