A Muslim father and son engrave the headstones at one of India’s oldest Jewish cemeteries

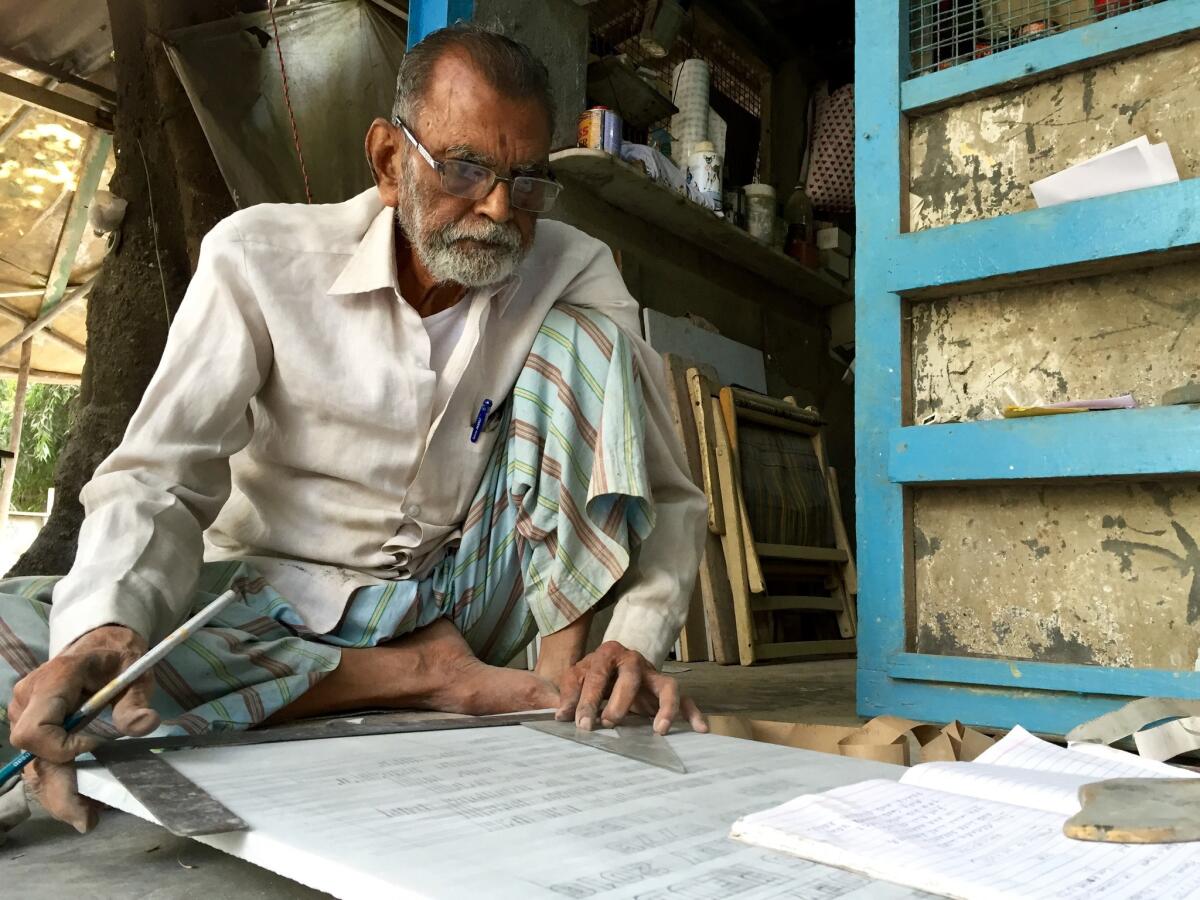

Reporting from MUMBAI, India — Mohammad Abdul Yaseen sat cross-legged beside a tree, hunched over a smooth marble slab. He moved a metal straightedge into position, making a gentle scraping sound, and drew a small line on the marble with a pencil.

He has done this for half a century, carefully etching the stones that mark the final resting places for members of Mumbai’s dwindling Bene Israel Jewish community.

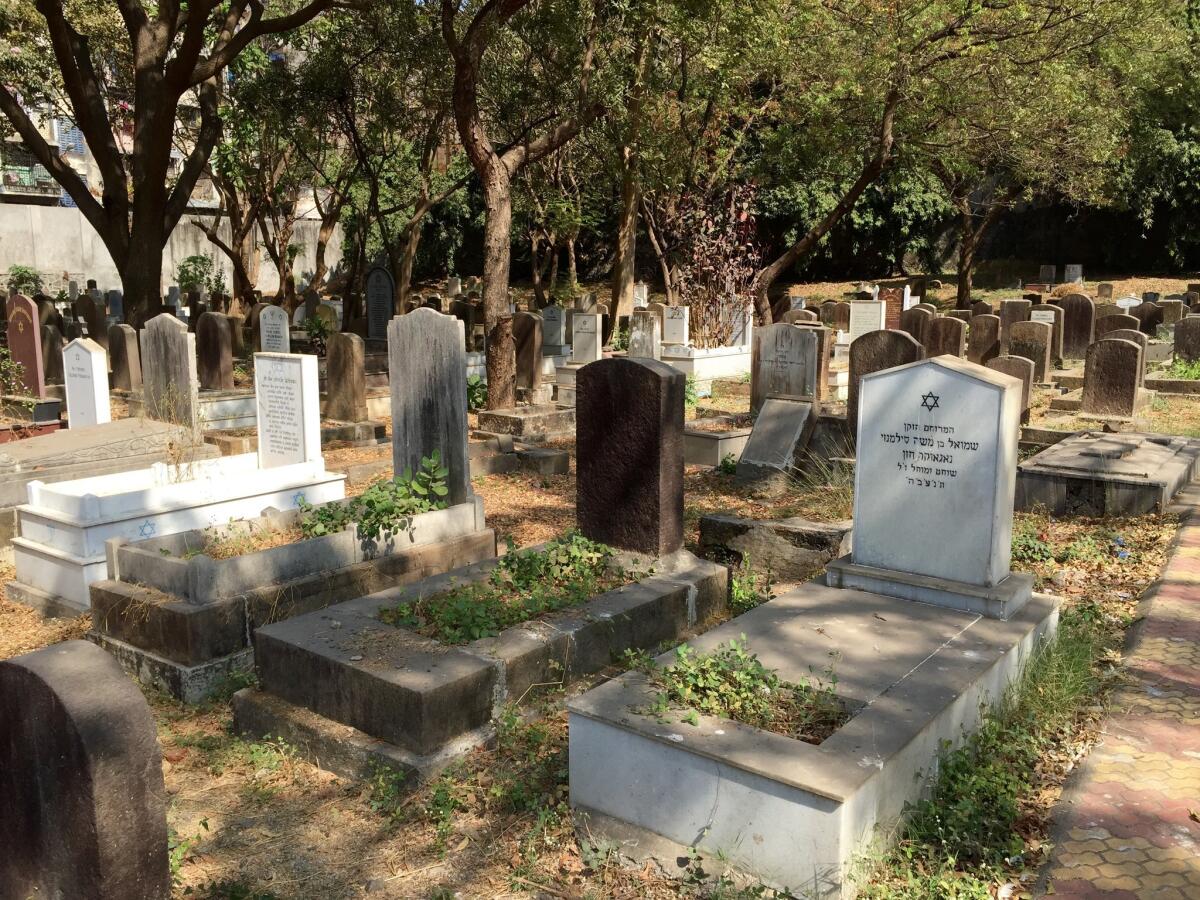

Behind him, the small graveyard unfolded across a quiet grove of trees in the city’s central business district. More than 6,500 tombstones, most adorned with the Star of David, rose in neat rows from patches of uneven grass. The blare of car horns and thrum of construction crews, the persistent soundtrack of India’s financial capital, seemed to fade inside the tidy cemetery.

Abdul Yaseen, 76, adjusted his glasses and wiped his brow with the sleeve of a crisp button-down shirt that he wore above a loose-fitting cotton dhoti. A small notebook lay in front of him, a stone holding open the page that bore the English epitaph that a family had asked him to sketch, for an 84-year-old woman who died in January:

“Till memory lives

and life departs,

You will live

forever in our hearts.”

At the top of the stone Abdul Yaseen had written a brief prayer in Hebrew. As a boy growing up in the northern agricultural state of Uttar Pradesh, he did not learn how to read or write in any language. When he moved to Mumbai in 1968 to look for work, he met Aaron Menasse Navgavikar, a Bene Israel Jew who engraved the community’s tombstones and was looking for an assistant.

Working with Navgavikar, Abdul Yaseen learned not only Marathi, the language of Mumbai and its surroundings, but also Hindi, English and Hebrew. When Navgavikar moved to Israel in the 1970s, Abdul Yaseen took over the practice.

He arrives at the cemetery, marked by a blue sign along a metal archway, around 9 a.m. and works until 1 p.m., except on Fridays, when he leaves earlier in order to attend prayers at his mosque.

Abdul Yaseen is an unassuming symbol of Mumbai’s polyglot heritage: a Muslim engraving Jewish headstones in a city that, like the rest of the country, is overwhelmingly Hindu. Although tensions between Hindus and Muslims have sometimes devolved into communal violence in India, there is less strife surrounding the smaller Jewish and Christian communities.

“India should always be mixed like this,” Abdul Yaseen said. “It doesn’t matter that I am Muslim. It only matters that the community has taken us in and treated us well.”

He brought his son, Islam, into the trade. Now it is the younger man, 53, who operates the heavy stone cutter and chisels the stone by hand. Abdul Yaseen’s body has grown frail, though his hands remain steady enough to sketch out the letters, which he does with the precision and concentration of a surgeon.

Their work may not pass to another generation. The Bene Israel Jews, who have lived along India’s western coast for two millennia, numbered 20,000 in the 1940s. But with India’s independence in 1947 and the creation of Israel the following year, many began migrating. There are roughly 2,000 Jews left in Mumbai and the surrounding state of Maharashtra, and fewer than 5,000 in all of India.

Islam led a visitor to the oldest grave marker at the cemetery, a simple white slab erected in 1927, and more recently encased in protective concrete. In Hebrew and Marathi, it memorializes Levy Isaac Charikar, who died almost exactly 90 years ago, at the age of 5.

Nowadays, Abdul Yaseen and his son get requests for only two or three headstones every month. Occasionally, a Christian church in one of Mumbai’s suburbs will give them some work. Hindus cremate their dead and Muslim graves rarely feature elaborate markers, so the market for their expertise is limited.

Abdul Yaseen, too, has been invited by community members to move to Israel, where he could continue to work. His wife died 15 years ago and his children — another son and two daughters — all have families of their own.

But he has not seriously considered leaving. He has never been outside India. These days, his life is confined to his small apartment, the cemetery and a mosque, all just minutes from one another on his bicycle.

“I’m as good as retired,” he said.

Islam, who joined the trade at age 19, has his father’s fine, slicked back hair and solemn eyes. Sweat gathered on his forehead as he maneuvered the stone cutter, noisily carving the granite into small squares that would adorn the 84-year-old woman’s grave.

His two sons never gave a thought to working at the graveyard. One got into a four-year training program at an outsourcing company that handles technical support for U.S. businesses. Another works as an engineer in Saudi Arabia and was recently married. With pride, Islam said his son had taken his bride on a honeymoon to Singapore and Malaysia.

“With his own money,” he said, smiling. “That is what boys these days want to do. We worked with our hands so that we could educate them, but it doesn’t mean we should do this forever.”

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

The elaborate ceremony that says everything you need to know about India-Pakistan tensions

Here’s why the idea of moving the U.S. Embassy in Israel remains controversial

An Indian charity battled caste-based discrimination for three decades. Then it became a target

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.