Cash chaos in India: An unprecedented ban on large bills backfires on the poor

A cash crunch gripped India after Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the unprecedented step of withdrawing the country’s large currency notes from circulation

Reporting from MUMBAI, India — The rickshaw meter read about $2.30, but passenger Gaurav Munjal didn’t have cash. The first ATM he and the driver found had a long line; the second was out of bills.

Frustrated, the 26-year-old tech entrepreneur asked the driver, “Do you want some rice?”

The two men drove to a department store and Munjal used a credit card to pay for an 11-pound sack of basmati rice that he deposited on the floor of the rickshaw, next to the driver’s feet.

“Good thing for the barter system,” Munjal said later in an interview. “Otherwise it was chaos.”

An exasperating cash crunch has gripped India in the week since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the unprecedented step of withdrawing the country’s large currency notes from circulation. Modi surprised the nation by announcing an instant ban on the 500-rupee and 1,000-rupee notes, worth about $7.50 and $15, respectively, and which account for 86% of the cash in the market.

The ban was billed as a sweeping move against corruption that would force Indians who hold large amounts of undeclared wealth to deposit the money at banks and make their assets official.

But it has stunned hundreds of millions of poor and working-class Indians who live an almost entirely cash-based existence, paying in bills for everything from rent to groceries to cellphone credit.

The plan was shrouded in such secrecy that even India’s financial institutions were ill prepared, creating long, sometimes unruly lines outside banks, ATMs and chronically understaffed post offices that are authorized to exchange the now-worthless notes and dispense new ones.

Indian media report that at least five people have died of exhaustion while waiting to change money outside banks, and that three children have succumbed to illnesses that private hospitals wouldn’t treat because their families had only old notes.

Credit and debit cards are unaffected, but only half of Indians have bank accounts. Even for those fortunate enough to find some cash — the government has set a temporary $66 daily limit for withdrawals — a newly released 2,000-rupee banknote is in effect useless for daily purchases because most merchants can’t make change.

Adding to the headaches is that the 2,000-rupee note and a new, revamped 500-rupee note are of a different size, meaning it could take weeks to reconfigure the country’s 200,000-plus cash machines to dispense them.

For now, that has made the 100-rupee note the basic legal tender for most transactions, reducing the world’s seventh-largest economy to trading largely in the equivalent of $1 bills.

The Wire, an online news site, called it “undeniably the most extraordinary situation India’s economy has faced since independence.”

At his roadside stall in central Mumbai, India’s financial capital, Ramesh Sisodia doled out steaming shot glasses of milky tea and coffee, the cheap and ubiquitous fuel for armies of Indian laborers and office workers, at 20 rupees a pop (about 30 cents). But Sisodia said some customers were trying to pay with 2,000-rupee bills.

“It is not their fault, but how am I going to cope?” Sisodia said.

His business had dwindled as his poorer customers chose to save their scarce small bills and richer ones opted for fancier coffee shops that take plastic.

“People don’t have money to buy bread — why would they stroll out for a coffee?” he said. “Those who can afford it would prefer to pay 10 times more for a coffee at Barista” — a Starbucks-like chain — “because they can pay by card.”

As one customer took out his wallet to pay, a 10-rupee note (15 cents) fell on the ground. A bystander alerted Sisodia, who thanked him and said, “It is a precious note these days.”

When the customer produced exact change, Sisodia said, “God bless you, my friend.”

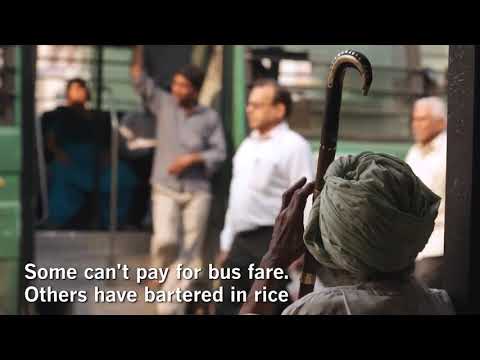

Blue-collar workers are not showing up for jobs, unable to scrounge up money for bus fare or fuel to power their motorbikes. Mumbai’s cash-based taxis and rickshaws have also struggled as middle-class customers opt for card-based services such as Uber.

Even filling up the tank has become a chore as gas stations, which have been authorized to accept the old bills for a limited time, refuse to make change, said Lallan Jaiswal, a cabby sitting idle by the roadside, his khaki uniform slung over the driver’s seat.

“They fill up the tank only if we buy gas worth 500 or 1,000 rupees,” Jaiswal said — the equivalent of a day’s worth of fares.

Neighborhood grocers who deal mainly in cash have offered to sell goods on credit, while some customers are bartering phone credit — bought with a credit card — for vegetables.

Such solutions fit into India’s longstanding tradition of jugaad, or ad hoc fixes. “But the middle class always suffers the worst,” said Kiran Gosrani, owner of a grocery in central Mumbai. “The big fish always get away.”

Indeed, many Indians are skeptical that the drastic action will end the scourge of so-called black money — the vast amounts of off-the-books wealth that accrue at the rate of an estimated $460 billion a year, more than the economy of Thailand.

Black money is an outgrowth of an economy in which cash accounts for two-thirds of the value of all transactions, one of the highest rates in the world, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. (In the U.S., it’s 14%.)

Much of the wealth that India has accumulated since economic reforms began in the 1990s has never been taxed or accounted for, parked instead in real estate, gold, foreign investments and, in some cases, bundles of cash sitting at home.

It is those stacks of bills that Modi, who took office 2½ years ago on promises to curb corruption, aimed to bring into the open. Supporters of the prime minister’s plan said those holding cash stockpiles would have to deposit them at banks, where huge amounts would draw the scrutiny of tax authorities, or allow their value to evaporate.

In a speech over the weekend, Modi asked Indians for patience until Dec. 30, the deadline for depositing the old bills, saying, “I promise you I will give you the India of your dreams.”

The chaos in the streets has overshadowed Modi’s rhetoric. But critics say that even if the policy had been smoothly implemented, black money would continue to flow from virtually every seam of a lightly regulated economy that presents endless opportunities for masking wealth.

In the short term, jugaad is not limited to the working class; the wealthy, too, are finding ways around the currency ban.

Officials have said that bank deposits of less than about $3,600 can be made with virtually no questions asked, to attract small-time savers. One employee in Mumbai’s diamond bourse, who requested anonymity to protect his job, said jewelry merchants were distributing bundles of cash to their employees and having them deposit it under their names, to be retrieved later.

“Employees willingly help out their bosses because they pay their salaries,” the person said. “At some places, even bank managers are helping them out because banks need rich customers.”

Parth M.N. is a special correspondent.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

Why millions of Indian workers just staged one of the biggest labor strikes in history

What it’s like to live in the world’s fastest growing major economy

Young men in Kashmir are disappearing from their homes. Friends say they’re going to fight India

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.