German Holocaust archive puts millions of documents online

Reporting from BERLIN — Sixteen women at the Buchenwald Nazi concentration camp were forced by the SS guards to work as prostitutes for 86 other inmates on the night of Aug. 7, 1943.

Stahlheber, Zange, Rathmann, Fischer, Kolbusch and Zimmermann — the last names of some of the women — embodied a painful story long kept from the general public. They are stolen lives, listed on a single page labeled “Bordel Receipts” — part of more than 13 million Holocaust-related documents retrieved from concentration camps at the end of World War II and uploaded online Tuesday in digital form by the International Tracing Service in Germany.

The international organization, which also announced Tuesday that it is rebranding itself the Arolsen Archives – International Center on Nazi Persecution, hopes that by making the documents widely available to the public it will help researchers and relatives learn more about the Nazi death machine. It’s the first time the massive volume of documents has been put online. Arolsen Archives is located in the north-central town of Bad Arolsen, Germany — about 90 miles north of Frankfurt.

The “Bordel Receipts” page, which also lists the number of fellow inmates — ranging from three to nine — each woman engaged with that night, was written in English on May 4, 1945, presumably by an Allied investigator as the war ended.

The list also details how much the women collected — 2 reichsmarks per customer, or just under $1, based on prewar exchange rates — and how much of those receipts they had to turn over to the prison camp guards named Fricke, Koch and Gust: more than three-fourths of the 172 reichsmarks they took in that night.

Arolsen Archives announced it had uploaded a vast trove of original documents that includes names and other information about 2.2 million people — those deported to concentration and forced-labor camps, death reports and postwar testimonies from many survivors. It will continue uploading more of the remaining two-thirds of the documents in its collection about many more millions of people in the months and years ahead.

There are also documents relating to some whose lives and work later helped enlighten postwar generations about the unfathomable darkness of the Holocaust: German industrialist Oskar Schindler, who tried to protect Jews from being deported and is credited with saving about 1,200 lives; Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel; and a young German girl named Anne Frank, who wrote “The Diary of a Young Girl,” published after she perished in the Bergen-Belsen death camp.

Run by the Red Cross after the end of World War II, the organization was long criticized for keeping extremely tight controls on the archives. The documents were recovered from Nazi death camps across Europe by Allied forces and deposited in the archives. Considerable pressure from the United States later helped force the partial opening of the records in 2007, an important milestone ahead of Tuesday’s full opening at the institution.

“These archives are the witness to the Nazi atrocities,” said Floriane Azoulay, the director of the Arolsen Archives, in a telephone interview with The Times. “It’s a very rewarding day for all those who have been fighting relentlessly for decades to have these archives opened. The survivors, their children and grandchildren who come here always tell us: ‘Don’t ever let these archives be buried. Keep them safe and show the world.’ This is what we’re doing today.”

Azoulay, a Frenchwoman who is 49 and has served as director for three years, said she hopes the worldwide publication of the first third of its documents would help scholars and survivors as well as the public at large to learn more about the magnitude of the Holocaust — thanks in part to the meticulous record keeping by the Nazis under Adolf Hitler. The records also serve, tacitly, as a bulwark against those who now try to deny the Holocaust ever happened — which, despite constitutional guarantees of free speech, is considered a serious crime in Germany and punishable with long prison sentences.

“Before 2007 the archives were not truly accessible for researchers or the public,” Azoulay said, noting that requests for information from survivors or scholars often took a long time and original documents not made available — because, it was argued, of Germany’s strict data protection and privacy rules.

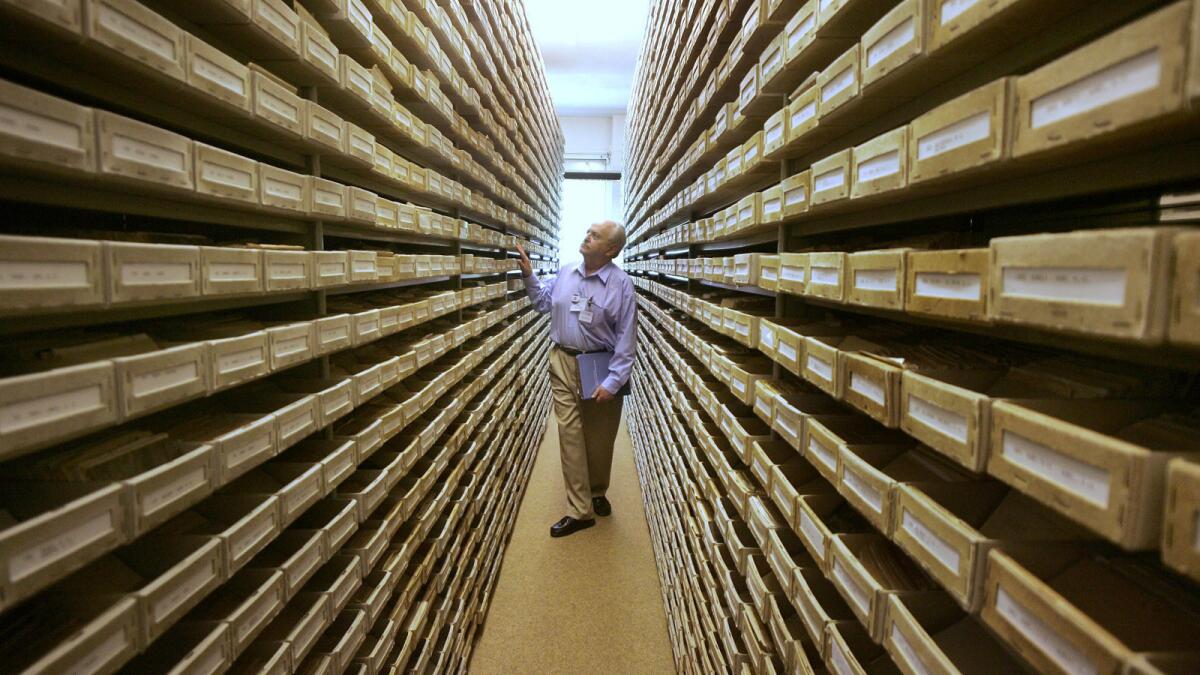

The files — one of the largest collections involving Nazi persecutions held anywhere in the world — would stretch to 16 miles in length if lined up and are kept in four large buildings in Bad Arolsen, a small spa town with a population of 15,000.

“Before 2007, it took a lot of time and the institution was not always fully forthcoming or transparent about the results of searches for information,” she added. “It was difficult for relatives of victims or survivors to get information. At the time, it was under the control of the Red Cross and it was their decision to keep the archives mostly closed for privacy reasons. Fortunately, that all changed.”

Pressure from the United States and in particular at a hearing in Washington by a House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 2007 helped get the archives opened for scholars and victims’ relatives later that year.

The Arolsen Archives, which was first set up in 1943 to help trace missing people, includes almost the entire collection of documents recovered from the two main Nazi death camps in Germany: Dachau and Buchenwald. The organization also collaborates with Israel’s Yad Vashem and the Holocaust museum in Washington.

The Arolsen Archives is larger but less known in Germany than another agency, the Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes in the southwestern town of Ludwigsburg. It was created in 1958 to deliver Nazi criminals to justice and oversees 1.7 million records of suspects, places and SS military units.

“Arolsen is one of the world’s most important collection of archives on the Holocaust and shows just how massive and methodic it all was,” said Hajo Funke, a political scientist at Berlin’s Free University and author of a new book, “The Struggle Over Memory,” about waning interest in studying the Nazi era in Germany.

“The documents were hidden away and inaccessible for far too long,” he said in an interview, adding there was only limited interest in postwar West Germany to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. “It’s very good news that they are opening it all online to the world.”

Kirschbaum is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.