Speculation swirls that the man who ruled Uzbekistan with an iron fist for 25 years may be dead. Here’s what might happen next

Reporting from ISTANBUL, Turkey — Only one man has ruled the Central Asian nation of Uzbekistan since it gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

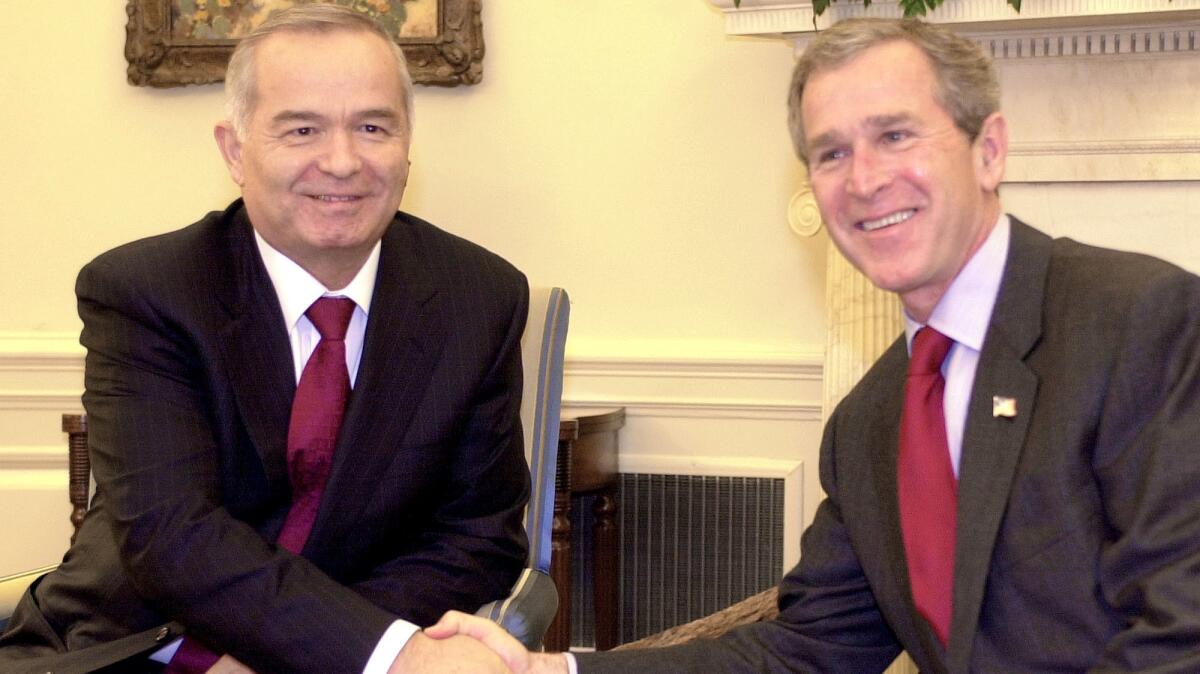

Islam Karimov was the Uzbek leader even before independence, and he has held on to power for more than a quarter of a century with all the tools at a despot’s disposal, his many critics say.

But Karimov’s grip on his country appears to be at an end, with persistent reports in recent days that he is either dead or dying. If those prove to be true, Uzbekistan will be facing a decision that none of its citizens has really made: Who will be its new leader, and what will that mean for a long-repressive society?

Karimov was last seen on state television on Aug. 17, and the government announced Sunday that he had been hospitalized. His daughter, Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva, who is the country’s representative to UNESCO, wrote on social media that her father had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, “and is now receiving treatment in an intensive care unit.”

Previous reports of Karimov’s death have turned out to be false, but this is the first time the government has made any acknowledgment of the 78-year-old’s fragile health.

“People don’t know what will happen yet,” said Adem Cevik, president of the Uzbek Assn. and Turkistan Union, groups that advocate for Central Asian migrants in Turkey. “They are not hopeful nor hopeless, but at least they hope the next leader will not be like Karimov.”

At the same time, social media were abuzz with persistent reports that he was, in fact, dead. A Moscow-based Central Asian news outlet, Fergana News, cited unnamed sources in the president’s office in reporting that Karimov suffered a stroke Saturday and died Monday. But Russian-language media cited other unidentified sources in Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital, as saying the president was still alive.

Under Uzbekistan’s Constitution, the head of the Senate, Nigmatulla Yuldashev, would take over for three months before elections must be held.

If, as in the past, the outcome of elections is predetermined, experts say, three candidates are most likely to replace Karimov: Rustam Azimov, the deputy prime minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the prime minister, or Rustam Inoyatov, the head of the security services.

Some opposition figures outside the country have said Azimov has been put under house arrest, but officials in Tashkent have denied this.

Karimov’s departure will leave an enormous power vacuum.

“All of state institutions directly depend on Karimov’s decisions,” said Erica Marat, an assistant professor at the National Defense University. “He was notorious for micromanaging any decision on security, economy and cultural life.”

Karimov’s decades-long sidelining of critics has meant day-to-day running of the state is now done by patronage networks loyal to one another.

“Anyone who succeeds Karimov will need to maintain similar level of loyalty among political leaders and engage in the same level of micromanagement,” Marat said.

A former KGB officer, Karimov was the head of the Communist Party in Uzbekistan on the eve of independence, which came on Sept. 1, 1991, as the Soviet Union splintered. He won the country’s first presidential election, which Human Rights Watch called “seriously marred.”

How The Times reported Karimov’s rise in 1991 »

In 1995, a referendum extended Karimov’s rule, and he went on to be reelected three times, the last two elections defying a constitutional two-term limit.

“The opposition has been exterminated,” said Nate Schenkkan, a researcher with Freedom House, which monitors democratic governance in Central Asia. “By the early 2000s, everyone was either exiled, imprisoned, or assassinated, including in countries outside of Uzbekistan.”

About 10,000 political prisoners are in jail in the country, many of them, according to Steve Swerdlow, the Central Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch, under falsified charges of belonging to Islamic extremist groups. Prisoners are routinely tortured, including at least one case of being boiled alive.

“Uzbekistan has been one of the most corrupt, repressive countries in the world for some time now,” said Swerdlow. “The 31 million people there have endured tremendous social repression and economic poverty.”

In an overwhelmingly Muslim country, praying in mosques not approved by the state is illegal, and there are severe restrictions on beards and head scarves, and the possession of religious literature. After 1991, Karimov banned the Islamist opposition Renaissance Party, members of which fled to neighboring countries, some later forming the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, a militant group that continues to fight alongside Al Qaeda and the Taliban.

Hundreds of members are now thought to be in Syria, some fighting with the militant group Islamic State.

Karimov, Schenkkan said, has used the threat of Islamic extremism in the past to attack political opponents.

“There’s a lot of anger, discontent, because of that in Uzbekistan, but it’s not really organized,” he said. “I think it’s unlikely there would be violent reactions [to Karimov’s death], and if we do see any, I would suspect they would be organized by parts of the state itself.”

Tashkent became vital for American operations in Afghanistan after 2001, with a base in the country used to ferry troops and equipment. In 2005, government troops opened fire on civilian protesters in the city of Andijon, killing several hundred and prompting a temporary halt to cooperation with Washington. The U.S. and Europe imposed a travel ban on Karimov and other top officials.

Economic stagnation has forced about 2 million Uzbeks to work in Russia. In Uzbekistan, the world’s fifth largest exporter of cotton, a million citizens are forced to leave school and other work to harvest the crop each year.

Under Karimov, Uzbek soldiers have clashed with neighboring Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan off and on for several years over border disputes that date to 1991. At least 50,000 Uzbeks have settled in Istanbul, Turkey, said Cevik.

“Karimov’s death is great news,” said Muhammad Salih, the head of the banned opposition Erk (or Freedom) Democratic Party, who has lived in exile in Istanbul for more than a decade. “First of all, I have to go to Uzbekistan. Then we have to organize the people for elections, for which we need the help of the international community.”

But Salih, a nationally acclaimed poet, acknowledges that free and fair elections are only a distant possibility. Without international support for free elections, he said, “the opposition will suffer, there will be 20 more years of dictatorship, and Uzbekistan will still not have a [democratic] political process.”

Farooq is a special correspondent.

Also:

NATO could be at its most critical point since the Soviet Union broke up

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff: My impeachment threatens democracy

Why Iran is desperate for U.S. passenger planes, but can’t have them

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.