75 years ago, she was an Army nurse. At age 99, she’s returned to Normandy to mark D-day

Former U.S. Army nurse Ellan Levitsky served in a field hospital in Normandy just after the D-day landings. She remembers a song she and her sister used to sing to each other.

Reporting from Sainte-Mère-Eglise, France — Former U.S. Army nurse Ellan Levitsky loved her service in a field hospital in Normandy just after the D-day landings, but will never forget the sound of young military men crying themselves to sleep.

Levitsky, 99, says hearing the wounded American “boys” being cared for at the 164th General Hospital on France’s Atlantic coast was traumatic.

“They were just kids, 18 or 19 years old. They were hurt and scared and they wanted to go home,” she said during an interview this week about her World War II military experiences.

Levitsky, in Normandy from the U.S. for the 75th anniversary of D-day on Thursday, turns 100 in December and her memory is sharp as a new pin.

She said she recalls being so cold in the winter of 1944-45 that she lighted a fire in the wood stove of the nurses’ tent using gin and set the canvas alight -- twice.

Another time, she was so fed up with tinned Army rations she visited a local farm and swapped her uniform shirt for a chicken; she opens a small jewel box and shows a wishbone from said fowl.

She also recounted how she signed the paycheck of her older sister Dorothy -- also serving as a nurse in Normandy after the pair refused to be separated -- and was threatened with a court-martial, and how she sneaked out through a hole in the military camp barbed wire to go dancing with another nurse and could not return because of an air raid alert.

Dorothy, fearing she was dead, was so relieved and angry when Ellan returned very much alive the following day, “she socked me in the face.” Just like that, Ellan said, waving her fist.

Levitsky spoke to The Times during a trip from her home in Milford, Del., for the commemoration of the D-day landings on June 6, 1944, the Allied operation that led to the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II. It was the first time she had returned to France without her sister, who died in December 2015.

“I’m happy to be here, but it’s bittersweet. My sister should be with me,” she said.

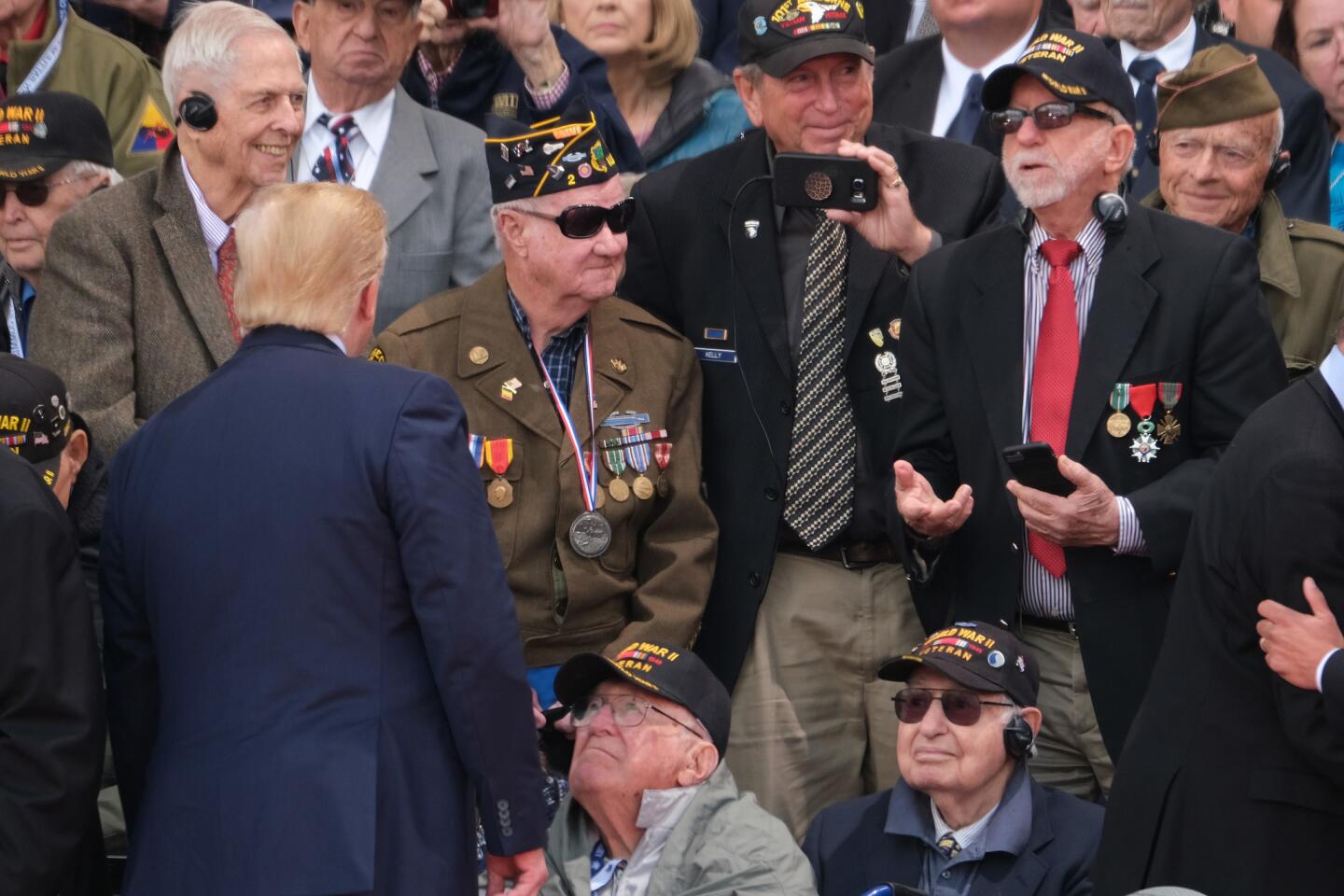

In Sainte-Mere-Eglise, the Levitsky sisters are held in great esteem by locals grateful for their war work. In 2012, François Hollande awarded them the Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest honor.

“Ellan is incredible,” says Francine Duchemin Noyon, who organizes exchange visits for World War II veterans of the 82nd Airborne Division who parachuted into Normandy on D-day.

“She is now part of my family,” Duchemin Noyon said. “For many years she came back with her sister. Now it’s just her. We thought it would be too difficult for her to be here this year, so it was a wonderful surprise when she called to say she just had to come. Normandy is her second home.”

Levitsky was the youngest of three sisters born in the U.S. after their Jewish parents fled Russia and settled in Salem, N.J. Their father died when Ellan was a baby, and she and Dorothy, who was 2 years older, became inseparable.

Both trained as nurses and as the war in Europe raged, both volunteered to join the Army. When the call came for nurses to serve in France, Ellan agreed to go if her sister went too.

“Dorothy was mad with me about that. Boy was she mad when I signed up and she had to come too because she didn’t want us to be separated,” she said.

“The war was on, they needed nurses badly and I just felt I had to do something,” she said. “I loved the Army, loved everything about it, but Dorothy hated every minute. She didn’t want to be in the Army and she didn’t want to go to France.”

The Levitsky sisters arrived in Normandy in August 1944 and worked at the makeshift hospital until it closed in May 1945. Dorothy was a ward nurse and Ellan trained as an anesthetist.

“We would see these kids who’d lost an arm, a leg. We had to give them hope, that was the only way to deal with it,” Dorothy Levitsky told French journalists in 2012.

Portraits of Normandy: U.S. veterans return 75 years after D-day »

After the Allied victory in Europe, the sisters were due to be sent on to the Pacific but instead shipped back home and got on with their lives.

“Within two weeks my mother had us working in the local hospital. We’re Jewish and she didn’t believe in lazy hands,” Ellan Levitsky said.

She pointed to the military hat on her head. “See this? That’s all I have of my uniform,” Levitsky said. “My mother burned them. At least I think that’s what she did because she wouldn’t tell us. She wasn’t happy about us going to France either.”

Her Legion d’Honneur medal was pinned to her jacket.

“In the U.S. nobody even looks at my medal. Here they come over and shake my hand and say thank you for being in Normandy,” she said. “Like the other veterans we went home and got on with our lives. My sister and I were so close, but we never ever talked about it. None of the veterans talked about what they did. It was too painful, too much.”

Levitsky’s eyes twinkled as she remembered the mischief she and her sister got into.

“Oh I do hope I’m not boring you,” she said. “Perhaps you’d like to hear a little song my sister and I used to sing to each other. It’s called: ‘Please, Mister Truman, Why Can’t We Go Home?’ ”

And with that, she burst into song.

Oh Mister Truman, we have got a point

We’re tired of living in this foreign joint

We don’t want the CBI [China-Burma-India theater]

Save that for another guy,

Please, Mister Truman, why can’t we go home?

We have met the Russians

And we have crossed the Rhine,

We are tired of vodka

And drinking Moselle wine

We would like to fraternize

But I said that’s not very wise

So please, Mister Truman, why can’t we go home?

We have conquered Berlin

And we have conquered Rome

We have destroyed the master race

So why is there no shipping space?

So please, Mister Truman, why can’t we go home?

Willsher is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.