One of the biggest breakups in history gets underway as Britain files to leave European Union

Reporting from London — It has been described as the most complex divorce in history, but Wednesday afternoon, the breakup began in earnest as Britain formally launched its move to leave the European Union.

Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, received a letter in Brussels hand-delivered by Sir Tim Barrow, Britain’s ambassador to the EU, which triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, setting off a two-year withdrawal process.

Minutes later, British Prime Minister Theresa May, who sent the letter to Tusk, announced in the House of Commons that her government was acting on the “democratic will of the British people,” who in June voted 52% to 48% to split from the 28-nation union.

The move Wednesday signifies one of the greatest political changes the continent has faced since the end of World War II.

The letter delivery kick-started a period of intense, probably fraught, negotiations that ultimately are expected to bring the end of a four-decades-old partnership and sever complex trade, immigration, legal and financial ties.

Some European leaders have emphasized that Britain cannot expect to have deals as good as the remaining 27 nations in the bloc. And EU leaders do not want to do anything to encourage other nations to follow Britain’s lead, weakening the group.

One sticking point is a potentially costly “divorce bill” based on future spending commitments that Britain could face, which, by some estimates, would be more than $60 billion.

The deals struck over the next 24 months are expected to fundamentally reshape Britain and Europe for generations to come.

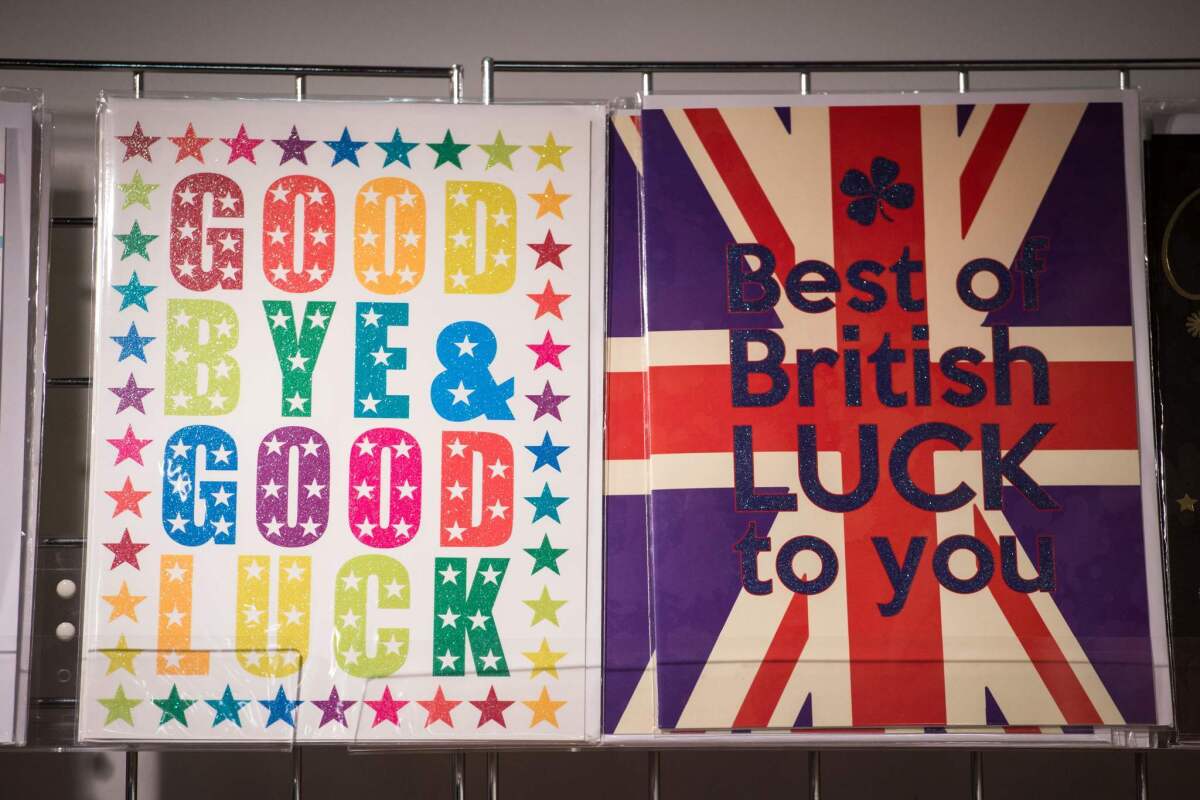

In her speech to lawmakers, May declared that “there can be no turning back” from this historic moment, describing it as a great time of opportunity for Britain and evoking the notion of the indomitable “British spirit.”

“At moments like these — great turning points in our national story — the choices we make define the character of our nation,” she said. “We can choose to say the task ahead is too great. We can choose to turn our face to the past and believe it can’t be done. Or we can look forward with optimism and hope — and to believe in the enduring power of the British spirit.”

She also implored all sections of society to come together after a fractious referendum campaign that bitterly divided the nation into two camps: “Remain” and “Leave.”

That task appears difficult to achieve as the very future unity of the United Kingdom — comprising England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland — is in question.

In Scotland, where 62% of voters in the June referendum favored remaining part of the EU, the Scottish parliament voted Tuesday in favor of an independence referendum within two years, once the terms of Britain’s exit deal are known.

In Ireland there are concerns about the future stability of the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement as the Republic of Ireland will remain in the EU, while Northern Ireland will be part of post- “Brexit” Britain.

Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny has warned that two decades of peace talks could be undermined if new border checkpoints go up and Britain potentially breaks from an EU customs agreement.

May, in her six-page letter to Tusk, included the Ireland-Northern Ireland issue as one of seven principles that British negotiators want high on the agenda in Brexit talks.

Political leaders and many observers say the status of the 3 million EU citizens living in Britain and more than 1 million Brits living abroad should be decided quickly.

“The most upsetting thing for any expat at the moment is that these rights could have been guaranteed,” said Adam Bowering, a British citizen working in the European Parliament in Brussels. “But now they’re being used as a bargaining chip in the negotiations.”

May does not want Brexit to be seen as Britain turning its back on its European neighbors, but instead as finding a new way to exist as an independent, sovereign nation while maintaining robust economic, trade and intelligence ties with the continent.

But she has also stressed that she would be willing to walk away from the negotiations at the end of two years with no deal, if the only option on the table is a bad one.

European leaders have set their own red lines and made clear that Britain cannot “cherry pick” the best parts of EU membership and reject the others as it seeks to forge a new relationship.

“It will never be outside the union better than inside the union,” Guy Verhofstadt, a European Parliament official and former Belgian prime minister, said in a Brussels news conference Wednesday.

“That is not a question of revenge,” he said.

The tone across the Channel on Wednesday was far from celebratory and Tusk struck a regretful tone during a news conference soon after receiving May’s letter.

“There is no reason to pretend this is a happy day, neither in Brussels nor in London,” Tusk said. “There is nothing to win in this process, and I am talking about both sides. In the essence, this is about damage control.

“What can I add? We already miss you,” he said.

EU leaders also sought to dispel fears that Britain’s departure from the bloc will create a domino effect, but there are looming threats to the union’s unity.

France will hold presidential elections in April and May, and Marine Le Pen, one of the front-runners from the far-right National Front party, has vowed to hold a referendum on France’s membership in the EU.

“Brexit has made us, the community of 27, more determined and more united than before,” Tusk said.

May’s letter comes on the heels of a celebration in Rome last weekend, where leaders from the remaining 27 EU countries pledged their commitment to a unified Europe.

But some cautioned that Britain will suffer outside the EU and should brace for an exit deal that will bruise foreign trade and cripple the nation’s economy.

Brexit would be “economically painful” for Britain, French President Francois Hollande warned.

In her letter, May seemed to imply that failing to reach an agreement could compromise Europe’s ability to fight crime and terrorism, which some EU leaders took as a veiled threat.

“Europe’s security is more fragile today than at any time since the end of the Cold War,” May wrote. “Weakening our cooperation for the prosperity and protection of our citizens would be a costly mistake.”

The prime minister’s office was quick to deny that was any sort of ultimatum.

The final deal will be put to the British Parliament for a vote and can also be vetoed by the European Parliament.

But there are already doubts a robust agreement can be delivered within two years.

“This is obviously one of the biggest blows that the EU has ever suffered,” said John Curtice, professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde. “We will discover how much unanimity there is on this subject.”

Special correspondents Boyle reported from London and Stupp from Brussels.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.