Just how far has North Korea gotten in developing long-range nuclear weapons?

Thousands of feet below the surface of the Pacific Ocean, secrets of North Korea’s ambitious nuclear missile program lie scattered over the seafloor.

If the United States or South Korea can find the wreckage of three missiles that failed over the last month, weapons experts say, it could provide insights into the military mysteries of a nation as closed to outside scrutiny as any power in modern history.

The U.S. Strategic Command tracked the missile launches in April, presumably after spotting them on U.S. early warning satellites and radar systems that ring the Pacific. It determined that the missiles were launched from North Korea and posed no threat to North America.

But that assurance provides scant comfort at a time when North Korea has stepped up the pace of both missile and nuclear weapons testing, fueling growing concern in the U.S., Japan and South Korea.

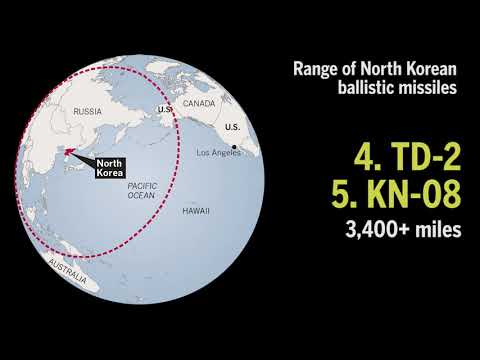

The latest tests involve missiles that could extend North Korea’s range to 2,000 miles, easily encompassing Japan, South Korea and a broad swath of China, and it is working on a missile that could reach more than 3,400 miles — enough to strike Alaska.

North Korea has stepped up the pace of both missile and nuclear weapons testing, fueling growing concern in the United States, Japan and South Korea.

The question that confounds U.S. experts is how much progress the North Koreans have made in recent years in developing long-range missiles that are accurate and reliable, along with miniaturizing powerful nuclear weapons that the missiles can carry.

Among the potentially important steps North Korea has taken involves the recent test of a new solid rocket motor, the type that the U.S. has used on its ICBMs since the early 1960s. The motor developed an estimated 15 to 20 tons of thrust and burned for about one minute, marking a threefold advance over North Korea’s existing small motors, said John Schilling, an analyst at 38North.org, a website affiliated with Johns Hopkins University that studies North Korea.

The motor would be an important incremental step toward an eventual multistage long-range missile, Schilling wrote recently. That missile is believed to be more than a decade away, he said.

At the site where the rocket was tested, North Koreans had inscribed a message on a wall in black and red paint: “To the American empire and the [South Korea President] Park Geun-hye party, a merciless bolt of lightning!”

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un was photographed before the test in front of the writing, sporting a fur hat, a long double-breasted coat and a broad grin. It was one of several recent appearances Kim has made at military sites and defense plants with modern, computer-controlled equipment in the background.

This year, Kim announced that North Korea had detonated a hydrogen bomb, a claim that alarms U.S. officials even as they question its validity. The detonation was detected by U.S. instruments, but its size was smaller than any analogous nuclear weapon in the U.S. stockpile. Such weapons use small atomic triggers to detonate hydrogen warheads.

It left analysts guessing whether it was just a trigger or a scaled-down two-stage system or a dud.

North Korea has steadily built its own base of missile technology, allowing it to launch a satellite into orbit in 2012. A Defense Department report to Congress last year described nine major North Korean ballistic missiles, including three versions of old Soviet Scuds that represent its largest force. The Scud, used by Iraq to terrorize Israel during the Persian Gulf War, has a range of up to 600 miles, long enough to reach anywhere in South Korea and most of Japan.

The three missile test failures in the last month have involved a North Korean missile known as the Musudan, apparently named after a cape on the northeastern corner of the Korean peninsula. The U.S. Defense Department describes the Musudan as a system capable of a range of 2,000 miles. It can be based on a mobile launcher, making it unpredictable and difficult to attack.

Michael Elleman, a former U.S. missile engineer and now an analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in Washington, said the missile looks similar to the old Soviet R-27 medium-range missile. If it is an R-27-type missile, it would represent a significant advance, because the propellant tanks are made with an etching process that makes them strong and lightweight.

“Their engines will succeed at making an ICBM someday,” Elleman said. “It depends on how much effort is allowed.”

If North Korea can make the Musudan operational, it would have enough range to attack Guam, a U.S. territory about 2,000 miles to the south with more than 100,000 American citizens and a major Pacific operating base, Schilling noted.

Existing North Korean missiles are grossly inaccurate by U.S. standards. About half of their Scud missiles would fall more than a mile from their targets. But they would still be useful for attacking cities, if the country can miniaturize a nuclear bomb. Elleman said North Koreans have made accuracy secondary to longer ranges, consistent with a plan to threaten cities with nuclear weapons.

The country has conducted four nuclear tests since 2006, though U.S. officials remain uncertain about their level of sophistication. Adm. Harry Harris Jr., who heads the U.S. Pacific Command, told the Senate that he is “not convinced” that North Korea detonated an H-bomb, but that its existing nuclear capability represents a global threat nonetheless.

That statement leaves open the possibility that North Korea has already achieved the ability to mount a nuclear weapon on one of its missiles. No doubt U.S. commanders will take that threat more seriously when the range and accuracy of North Korean nuclear missiles could threaten hard military targets, such as U.S. ICBM silos about 6,000 miles away.

North Korea is developing a three-stage missile, dubbed the Hwasong-13 or KN-08. The system has an estimated range of more than 3,400 miles, roughly the distance from North Korea to Anchorage, making it a legitimate intercontinental ballistic missile, according to the Pentagon report to Congress.

Wreckage of a Taepodong-2 missile, the system used to launch satellites, was retrieved from the Pacific in February, according to the South Korean Defense Ministry. The same type of retrieval is probably being conducted for the Musudan wreckage.

“It looked like a pretty bad failure,” said Philip Coyle, a former nuclear weapons manager, Obama administration advisor and top Pentagon official. “I imagine we have been able to get a hold of some of the hardware from their tests.”

Beyond the questions about North Korea’s technological achievements, top U.S. military officials acknowledge they don’t really know what makes Kim tick and exactly what policies will limit his threatening ambitions.

Asked whether he would suggest using military force to stop a nuclear missile capability, Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, chief of U.S. forces in South Korea, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in late February, “If military force was necessary — yes, sir.” Scaparrotti did not elaborate.

The U.S. based tactical nuclear missiles in South Korea for decades until they were removed in the 1970s.

Over the weekend, Kim said in a speech to the Workers’ Party Congress that he would not order the use of his nuclear weapons unless his nation is “encroached upon” by another nuclear power, presumably referring to the 25,000 U.S. troops poised near its border in South Korea.

North Korea’s ambition to develop a nuclear missile dates in part to the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, when the Soviet Union backed down in a confrontation with the United States, and Kim’s grandfather decided he could not rely on an outside power to guarantee North Korean security, said James Person, a historian on North Korea at the Wilson Center, a think tank in Washington.

The North Koreans are more accurately described as “anticolonial nationalists” than true Marxists, Person said, meaning they distrust China and Russia almost as much as they do the U.S. and South Korea. Their goal ultimately is to protect the Kim family’s hold on power and the patronage system it provides to senior officials.

The system the Kim family has built relies on a large military industrial complex that dominates the struggling economy, which ranks with Haiti and Rwanda in terms of per capita output, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s rankings. The country has run a shadowy arms trade that accounts for most of its exports, sending artillery and rocket systems to nations in Africa and the Middle East. It is believed to have traded missile technology with Pakistan, Syria, China and Russia, accounting for some of the designs of its existing operational missiles.

The existing North Korean missile threat has prompted deployment of an extensive network of ground- and sea-based radars and defensive missiles by U.S. and Japanese forces around Japan in recent years.

A similar network protects South Korea, and U.S. military officials are discussing the possible deployment of an even more capable high-altitude missile defense network, prompting protests by China.

The Chinese protests illustrate one of the ultimate risks of the North Korean missile program. It is not the probability that North Korea would launch a suicidal nuclear attack, but that its growing power will destabilize East Asia, said John Pike, a defense analyst at GlobalSecurity.org. Pike said Japan could feel so threatened that it develops its own nuclear weapons.

“The Chinese will go nuts if Japan develops a nuke,” Pike said.

ALSO

North Korea detains, interrogates, expels BBC journalist

North Korea ruling party gives Kim Jong Un a grander title: Chairman

In North Korea and trapped in a real-life version of ‘Waiting for Godot’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.