After a Hindu mob lynches a Muslim teenager in India, his family asks, ‘Why are they allergic to us?’

Reporting from Khandawali, India — Saira Bano slumped in a plastic chair, her delicate face drawn with grief. A white shawl covered her hair; bangles hung silently from her wrists.

Lying on a bed was Shaqir Khan, 23, the third of her eight children, his eyes cast toward the ceiling. His slim torso was swathed in a bath towel, concealing coin-sized gashes in his biceps and chest. He struggled to speak.

The quiet sorrow that filled the house, in a tidy village an hour’s drive from New Delhi, stood in contrast to the national outcry over the family’s loss: Three weeks ago, Saira’s sixth child, 16-year-old Junaid, was stabbed to death on a train ride home from the capital. Shaqir and another brother were wounded.

The brothers said they were targeted for being Muslim, a large but increasingly beleaguered minority in a country dominated by Hindus and led by a powerful Hindu nationalist party. A mob of passengers called Junaid and his brothers “beef-eaters” — a slur among orthodox Hindus, who regard the cow as sacred.

It was a ludicrous charge, their mother said. “My husband is a taxi driver,” Bano said, her eyes narrowing. “He makes 8,000 rupees [about $120] a month. Do you think we can afford to eat meat?”

Along a narrow brick lane fringed by an open sewer, Hindus and Muslims live side by side in Khandawali in simple concrete houses. They subsist as farmers and laborers or commute to menial jobs in New Delhi — not on the capital’s modern, air-conditioned metro rail line but via the cheap, suburban train that Junaid used.

The fare is 20 cents and trains are almost always filled. The fight that led to Junaid’s death, his brothers said, began as a dispute over a seat.

The lynching of a teenager appeared to mark a troubling new low in a trend of mob attacks by self-styled “cow protectors” in India. Over the last two years, as several Indian states toughened laws regulating cattle slaughter, dozens of Muslims and other minorities have been attacked on suspicion of possessing beef.

The week after Junaid’s stabbing, demonstrators organized vigils in several Indian cities, prompting Prime Minister Narendra Modi to declare that killing in the name of cows is “unacceptable.”

But within hours of Modi’s speech, another Muslim man, a meat trader, was beaten to death in Jharkhand state because of rumors that he was selling beef.

India’s nearly 200 million Muslims are finding their status in this country of 1.3 billion ever more precarious. Modi has appointed a Hindu extremist to lead India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh. As attacks have grown against Indian forces in the disputed Muslim-majority border territory of Kashmir, Indian Muslims are commonly branded with epithets like “Pakistani” and “anti-national.”

Junaid’s brothers said their attackers called them those names and others. “Beat the kattaley,” they shouted, which means “those who are circumcised.” One man tried to tug the beard of Junaid’s brother Hashim, 21, then threw his skullcap to the floor and stomped on it before another assailant pulled out a knife.

At the station near their village, the crowd stopped the brothers from getting off the train. The brothers finally escaped at the next stop, where cellphone video shows Junaid, covered in blood, lying motionless in Hashim’s arms as bystanders look on.

Six men have been arrested, including a 30-year-old who police said confessed to the stabbings.

It was a bleak end to what had been a joyous holy month of Ramadan. Since age 7, Junaid had studied Islam, telling his parents he hoped to leave the village and become an imam at a big-city mosque.

He was a sensitive boy and eager not to be a burden. Once, when he fell sick as a child, he told his siblings to hide his illness from his father to save the family the expense of calling a doctor, his family said.

The night before the attack, relatives and elders had gathered at their single-story home to hear the slight, bookish teenager, dressed in his best shalwar kameez, recite verses from the Koran. He earned the title of hafiz, meaning “one who has memorized the Koran,” and handed out sweets as his mother beamed.

“Only God knows how happy I was,” she said.

With about $75 in gifts from his recital, Junaid and his brothers set off for New Delhi in the morning to buy gifts for the Eid holiday that marks the end of Ramadan. Their father, fearing the train would be overcrowded, offered to drop them off in his taxi — but the young men preferred to be on their own.

“I did not think they would be in any danger,” said their father, Jalaluddin, 50, his eyes red and downcast. “I was born in this village and I’ve never heard of any incident like this. We have always lived happily with Hindus here.”

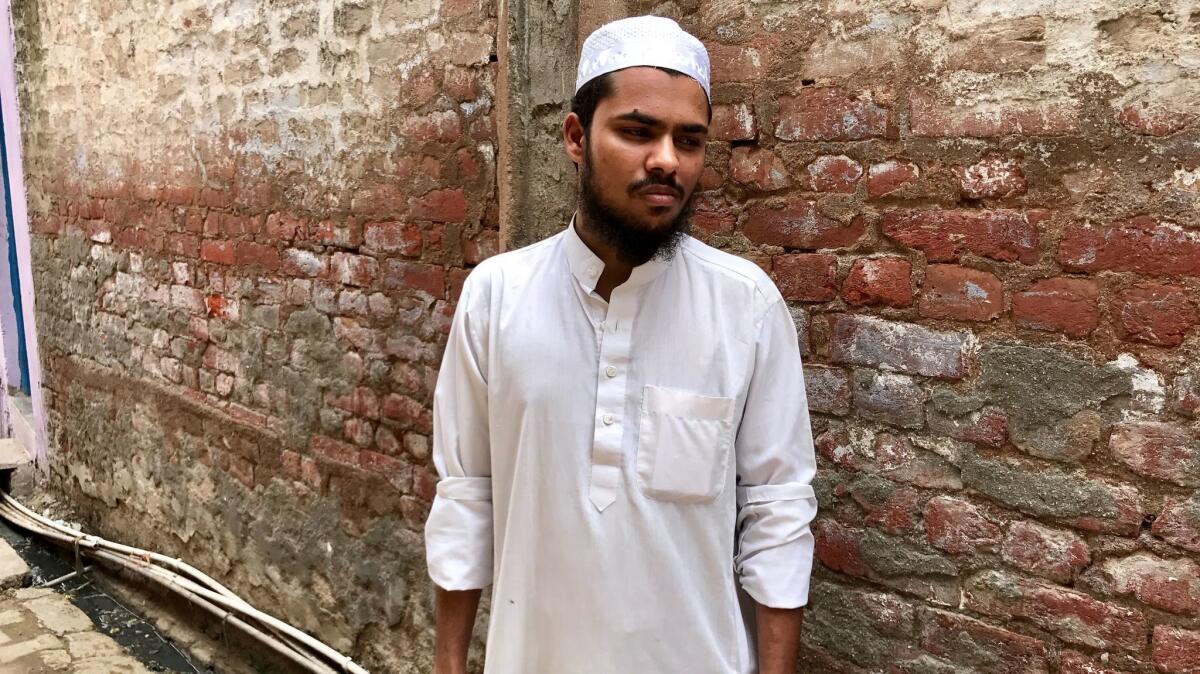

Seated next to him on the floor, wearing his white skullcap, Hashim, who studies at a seminary in the western city of Surat, leaned over.

“Papa,” he said, “you heard what happened yesterday?”

A group of Hashim’s schoolmates from the village had boarded the train back to Surat after the holiday, he said, when other passengers began peppering them with epithets. They stayed quiet for nearly the entire 14-hour journey.

“As soon as I get on a train now, if I am wearing a cap or because of my beard, I hear non-Muslims start talking among themselves about our appearance,” he said. “This kind of environment is happening because there are powerful people who want it to happen. Those of us who have no power, we can’t fight it.”

Hearing the story of Hashim’s friends, Jalaluddin’s eyes welled.

“My sons are scared of even going to the next village,” he said finally. “I can’t understand why the prime minister can’t stop what happened to Junaid, or why he doesn’t want it to stop. We are Muslims born in this land; we have nothing else but this land. Why are they allergic to us?”

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for more news from South Asia

ALSO

Fake news fuels nationalism and Islamophobia — sound familiar? In this case, it’s in India

Life in an Indian slum: Piped water and metered electricity, but the bulldozers can come at any time

The U.S. may have one card to play against North Korea: trade

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.