I watched the 1989 Tiananmen uprising. China has never been the same

Reporting from Tokyo — In the predawn hours of June 4, 1989, the Chinese army was bringing a bloody end to seven weeks of student-led protests centered on Tiananmen Square, Beijing’s historic center.

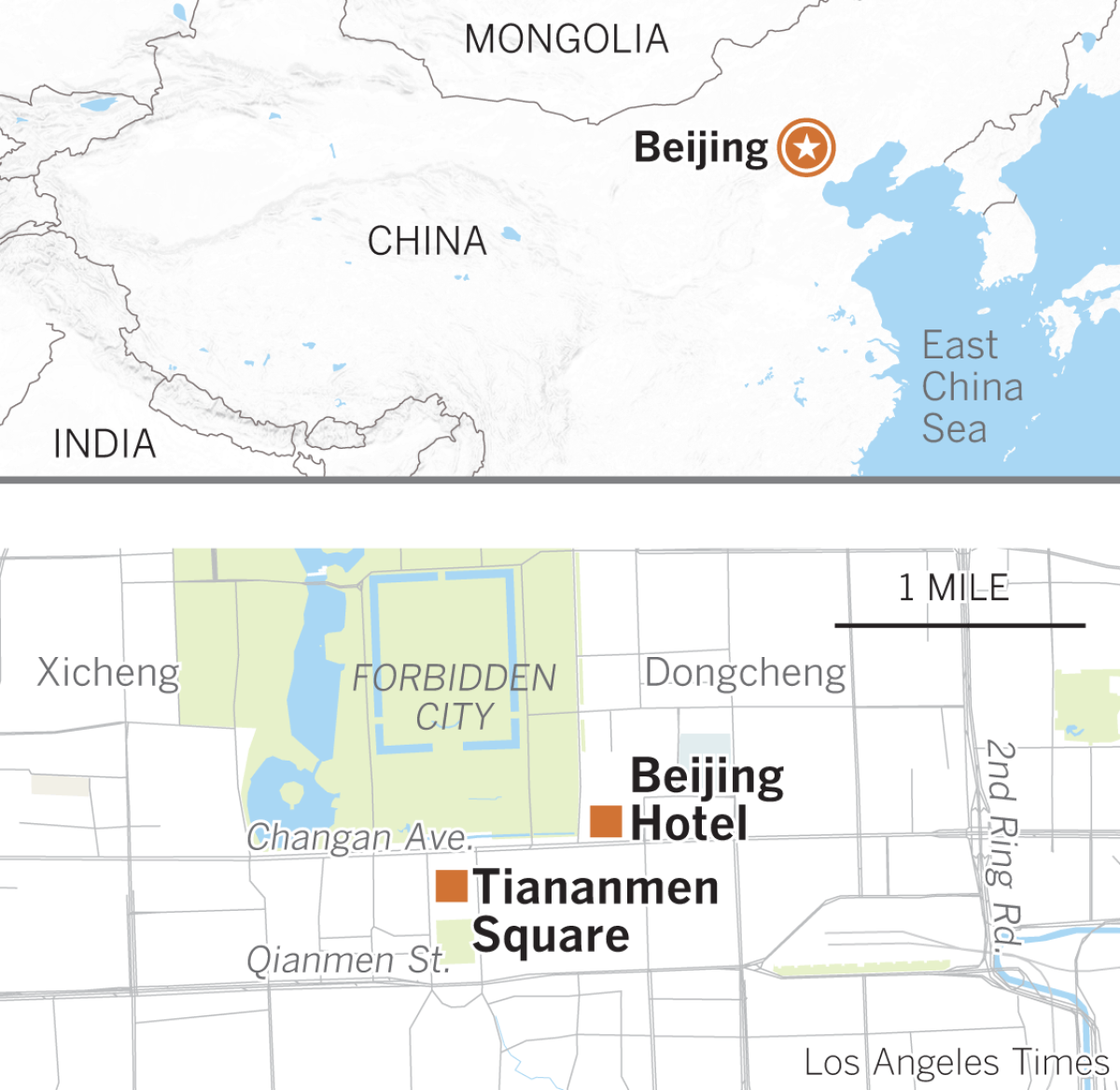

From the windows of a deserted coffee shop at the Beijing Hotel, a few hundred yards east of Tiananmen, I could look toward the square and see several hundred soldiers forming lines across the capital’s broad main street. In front of the hotel was an angry and brave crowd of a couple thousand Beijing residents. These protesters were furious at the army for shooting its way into the city center, tanks and armored personnel carriers smashing obstacles, soldiers spraying bullets at crowds blocking its advance. Now I watched as the soldiers periodically fired into this crowd.

For me, what the Chinese call simply “June 4” — a date that fundamentally shaped today’s China — had begun the previous evening.

I was the Los Angeles Times Beijing bureau chief then, and had overseen the newspaper’s coverage of the pro-democracy protests since they began in mid-April. The Times’ team had been taking turns staking out the square, and my shift was to begin at midnight. Before leaving home late on June 3, I learned that the army had begun smashing its way through crowds several miles west of Tiananmen.

I grabbed my bicycle and raced toward the square.

As I pedaled, I passed hundreds of Beijing residents fleeing on foot and bicycle away from the square and the main body of troops approaching from the west.

Soon a single armored personnel carrier came hurtling around a corner, headed toward the square. As it clambered over red-and-white concrete traffic barriers placed by protesters, I nearly kept up with it, weaving my own way around the barriers — which might stop trucks and cars but not tanks and bicycles. Finally the driver stopped when he encountered too thick a crowd on a side street at the northeast corner of the square. It seemed he was unwilling to start killing masses of people by running them over. Once the armored vehicle stopped, someone thrust a thick metal bar into its treads.

The furious crowd threw burning blankets and Molotov cocktails onto the vehicle; a few young men got on top and began banging the hatch. They managed an opening and started throwing burning objects inside. Three soldiers jumped out, scattering into the crowd. I followed one, and watched as he ran in a zigzag pattern while being severely beaten with pipes and sticks. Blood dripped down his face, which held a look of terror. Then two or three students grabbed him away from his tormentors, who almost certainly were not students, and put him into a nearby ambulance.

From the archives: The Times’ Tiananmen coverage from 1989 »

I interviewed students at the center of the square, who planned nonviolent resistance to the end, and nonstudents, more inclined to fight back, who dominated the fringes. I moved from the pedestrian part of the square onto Changan Avenue, which passes the famous portrait of Mao Tse-tung on Tiananmen, the Gate of Heavenly Peace.

Then I realized that I was within bullet range of soldiers.

I decided to telephone the bureau from the Beijing Hotel — mobile phones were still a rarity in Beijing at the time. At the hotel entrance, security searched me for cameras or film. I found a phone in the dark coffee shop, and to my relief the hotel operator put me through to my office. I watched the shooting through the windows and periodically phoned in more notes.

Rumors and unconfirmed reports spread among the international reporters, Chinese and other foreigners in the hotel, and many inside came to believe that the sounds of gunfire audible from the direction of the square meant the students who stayed behind were being killed. I figured that was probably what was happening.

Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor as China’s paramount leader, had ordered the army to take the square by dawn — and authorized it to do the killing necessary to achieve this. The slaughter ranged over much of the city, mostly along several miles of the western approach roads to Tiananmen.

The Tiananmen uprising came during a fateful year in which communism was under siege in Eastern Europe. The Berlin Wall would fall that November; two years later, the Soviet Union would cease to exist. Deng’s fateful decision may have been timed in part to a desire to clear the square before a June 4 election that would end communism in Poland. Deng was not seriously afraid of the students, but he did fear a Polish-style Solidarity movement.

The months of protest in China had been triggered by the death of a popular former Communist Party leader, Hu Yaobang, who lost the party’s top post in 1987 partly on charges of being too soft on protesters. In the spring of 1989, students were planning pro-democracy demonstrations for the 70th anniversary of a watershed protest on May 4, 1919. The students moved their plans earlier by bringing wreaths to Tiananmen Square to honor Hu upon his death.

That was an implicit criticism of the surviving leaders. Yet it was difficult for the police to immediately suppress this because superficially it began as mourning for a top Communist.

Officials under Deng divided bitterly over the protests, which gathered momentum during a visit by Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev in mid-May.

When Deng decided to use the army to clear the square, Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, the leading economic reformer who was relatively liberal politically, refused to go along.

Word of Zhao’s opposition leaked, and when troops tried to enter the capital on May 20 massive crowds blocked them. The people of Beijing, supporting the students’ calls for more freedom and an attack on corruption, peacefully held their country’s army at bay for two weeks, as the protests morphed into an attempt to force Deng out and perhaps throw power to Zhao. But by then it was too late: Zhao was under house arrest, and Deng along with the other tough old warriors ruling China had no intention of losing this battle.

A bit after sunrise, I saw my friends Dave Schweisberg, the bureau chief for United Press International, and Cynde Strand, a CNN camera operator, approaching the hotel. If Cynde tried to enter with videotapes she would lose them, so I opened the window and called out a warning. They told me they had stayed in the square to the end, within sight of the students gathered in the center, who left in a large column at dawn.

That was significant. The gunfire we heard from the square after 4 a.m. had been warning shots and soldiers shooting out loudspeakers that students had hooked up. The earlier, deadly gunfire, some of which I had witnessed, had been along Changan Avenue, which crosses the north end of the square and past the Beijing Hotel.

After telephoning the bureau to pass along what Schweisberg and Strand had told me, I got talking with a couple of American men, at least one of them a student. That gave me an idea. If I tried to rent a room, I’d have to show documents showing I was a journalist, and perhaps trigger trouble or be turned down. But they wouldn’t arouse suspicion. So I suggested that the Los Angeles Times would pay for them to get a room to share on an upper floor facing the street, with a better view of the continuing face-off between troops and protesters.

Soon I was on an upper-floor balcony with a spectacular view of the northern tip of the square, with tanks, armored personnel carriers and soldiers in that direction, and the seemingly fearless crowd of enraged ordinary citizens below us and to the left.

I have never been one to hold regrets over what might have been, but for a moment I wished I had been on that perch overnight — forgetting that I would have missed the vital conversation with Schweisberg and Strand. Then in the red brick side wall of the narrow balcony, I spotted a single bullet hole, right where my head would have been.

No regrets ever again, I thought.

About 24 hours later, I slipped out of the hotel, got on my bicycle, and rode back to the bureau to resume work from there.

Shortly after I left, Associated Press photographer Jeff Widener arrived, bumped into one of the men I’d shared the room with, and a few hours later, from the balcony of that room, took an iconic photo of a man standing in front of a column of tanks heading east from the square. A few other photographers captured similar images.

In the West, those “Tank Man” photos were seen as embodying the brave spirit of human resistance to evil. But because the tank stopped instead of running over the man, China was able to use the incident in propaganda claiming that troops had exercised great restraint.

More important, Chinese television news reported that violence by protesters triggered the army actions, rather than the truth that the army’s brutal thrust into the city triggered the citizens’ violence.

Tiananmen Square mystery: Who was ‘Tank Man’? »

These tricks, combined with censorship and control of what can be seen on the internet, have created a situation in which most Chinese today have little clear idea of what happened. Many only know that there was an event called “June 4” that no one is supposed to talk about.

On June 9, Deng emerged and praised the army as “the bastion of iron of the state.” He stressed that China would continue his basic policies of economic reform and openness to the outside world. The Times ran a three-column headline: “Economic Reforms to Continue, Deng Vows.”

“This incident has impelled us to think over the future as well as the past sober-mindedly,” Deng said. “It will enable us to carry forward our cause more steadily, better and even faster and correct our mistakes faster.”

This Beijing massacre ultimately strengthened Deng’s control and froze into place his formula for China’s modernization: one-party dictatorship paired with market-oriented reforms. In other words, a Chinese version of authoritarian capitalism. His turn to violent suppression marked the end of any leftist ideological legitimacy enjoyed by the Communist Party, leaving only military and police state power, economic growth and fervent nationalism as pillars of support.

Over the last 30 years, China has grown stronger and more prosperous, but the formula remains unchanged.

The massacre also cut off the option of evolution within the Communist Party, perhaps under a softer leader such as Zhao, that might have ultimately brought political liberalization along the lines of what Gorbachev gave the people of the Soviet Union. Ever since the Soviet collapse, the Chinese leadership has cited Gorbachev’s softness as a cautionary tale.

A few months after the events at Tiananmen Square, I was at the U.S. Embassy when an American official asked me how many people I thought had died in the crackdown. I replied that I thought it was about 1,000. He looked surprised, apparently expecting me to cite a much higher number, since many media reports suggested far more probably died. He then told me that U.S. and Western European intelligence had cooperated to come up with their best estimate of the number dead, and that 1,000 seemed to be about right.

This same intelligence estimate is cited in a definitive 1992 Harvard report, “Turmoil at Tiananmen: A Study of U.S. Press Coverage of the Beijing Spring of 1989,” which says a group of Western military attaches conducted a secret inquiry and came up with the estimate of 1,000 to 1,500 dead.

I now teach history and politics at Waseda University in Tokyo, including a seminar about the Tiananmen Square protests and their historical context. I tell students that about 1,000 people died, including roughly 800 ordinary residents, mainly people blocking the army’s advance. I estimate that 50 to 100 students from Beijing and the provinces were killed, but none or almost none of them inside Tiananmen Square’s pedestrian area. I accept a 1989 Chinese government figure that “several dozen” soldiers and police were killed by protesters.

I also tell my classes, “If you want to understand today’s China, imagine that the Chinese Communist Party met and changed its name to ‘the Rich and Strong China Party.’ That’s all. If you think of China as being under the dictatorship of ‘the Rich and Strong China Party,’ using capitalism to pursue its goals, suddenly everything becomes clear.”

It is this freezing into place of authoritarian capitalism, for a generation and probably many more years to come, that is at least for now the key legacy of June 4. But these events will not remain hidden in China forever. Their memory, ineradicable, may yet profoundly shape China’s destiny.

Holley was a foreign correspondent for The Times from 1987 to 2007, based in Beijing, Tokyo, Warsaw and Moscow.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.