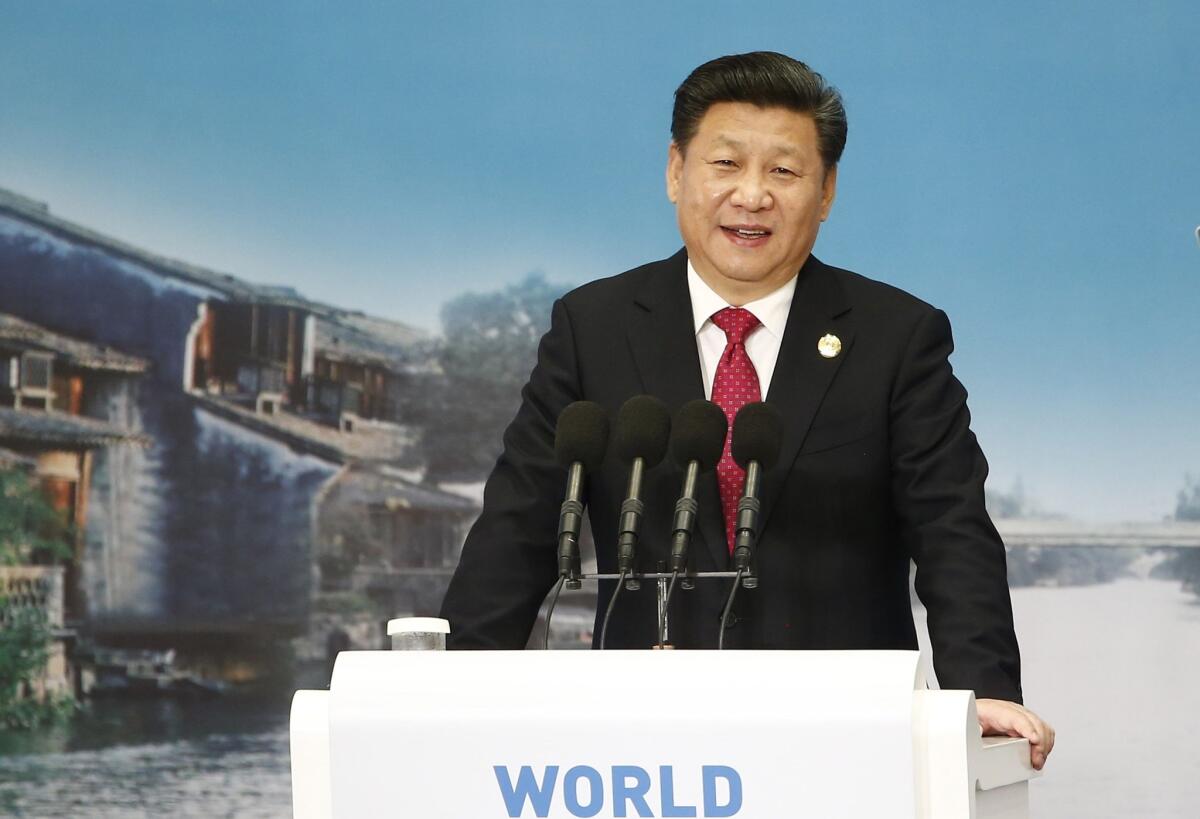

China’s president is the country’s most-traveled leader since Communism -- and maybe the strongest

Chinese President Xi Jinping visited 14 countries in 2015.

Reporting from Beijing — This year’s list of top globe-trotting heads of state included a surprising upstart: Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Xi has visited 14 countries in 2015, making him China’s most-traveled top leader since the Communist Party took power in 1949. His predecessor, Hu Jintao, visited only seven countries during his decade as China’s top leader. Since Xi took the reins in 2012, he has visited more than 30.

The diversity of his destinations was also striking. In 2015, he visited Pakistan, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, the U.S., the United Kingdom, Vietnam, Singapore, the Philippines, Turkey, France, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

“Xi is absolutely a high-profile foreign-policy president,” said Xie Tao, a professor of international relations at Beijing Foreign Studies University. “Rather than only bringing in business contracts for Chinese enterprises, Xi wants to gain more political influence [abroad].”

Naturally, the old guard of presidential travel continued to rack up miles in 2015: President Obama traveled to 11 countries, Russian President Vladimir Putin to 14 and French President Francois Hollande more than 50.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

But analysts say that Xi’s peripatetic style makes a fresh statement about China’s foreign ambitions and marks an effort to reshape perceptions of Beijing both at home and overseas. Domestically, he may hope that a dramatic foreign policy agenda will divert attention from widespread concerns about a protracted economic slump (China’s economy grew 7.3% in 2014, the slowest annual pace since 1990). Internationally, they say, he wants to show that China’s political clout can now match its economic gravitas, allowing the country to challenge the United States as a geopolitical superpower.

“When China’s internal economic growth is slowing down, Xi and the Communist Party have to show Chinese people that China is playing a bigger role externally,” said Willy Lam, an expert on Beijing’s foreign policy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “I don’t see a physical war between China and the U.S. in the near future, but the competition between the two countries will definitely grow more and more fierce,” he added.

Xi has developed several high-profile international institutions to rival those of the West, signaling that his ambitions stretch beyond the next few years. His multibillion-dollar Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, a Beijing-based alternative to the World Bank, has attracted a slew of U.S. allies as founding members; his One Belt One Road initiative, a massively ambitious development strategy, involves plans to establish trade routes throughout Asia and Europe.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Xi has inked $130 billion in business deals while abroad this year alone, worth more than the total gross domestic product of many small nations. These include a $7.7-billion deal with the Toulouse, France-based aircraft manufacturer Airbus to buy 70 commercial passenger planes; a $5-billion deal to build a high-speed rail line connecting Los Angeles and Las Vegas; and a $3-billion deal to build two “ecological parks” in Wales.

Yet Xi has complemented his deal-signing with increased aggression in the South and East China seas, ratcheting up tensions with Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and the Philippines.

Beijing is attempting to bolster its claims by building artificial islands made of dredged-up sand in disputed maritime territory near the Philippines. In October, the United States — which does not recognize China’s claims — sent a guided missile destroyer within 12 nautical miles of the islands, drawing harsh rebukes from the Chinese foreign ministry.

In September, Xi held a massive military parade in central Beijing to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Although many Chinese saw the display — which featured 12,000 troops, as well as dozens of tanks, missiles and planes — as a reassuring sign of national strength, many foreign observers saw it as an unnerving display of military might.

Commentators have called Xi the strongest Chinese leader since Mao Tse-tung and say that foreign leaders have taken note of his unusually powerful position. “In the Hu era, other countries sometimes weren’t so sure whether to listen to Hu or China’s Foreign Ministry, [especially] when the two sides weren’t in perfect consensus,” said Shi Yinhong, a professor of international relations at Renmin University of China in Beijing. “But everyone now knows that if you want to deal with China, you need to deal with Xi Jinping.”

This year, a group of Harvard University researchers showed that 12 of 16 historical instances in which a rising power has confronted a ruling power have resulted in war. In September, Xi himself addressed the theory — called the Thucydides Trap — head-on in Seattle during his state visit to the U.S.

“There is no such thing as the so-called Thucydides Trap,” he said. “But should major countries time and again make the mistakes of strategic miscalculation, they might create such traps for themselves.”

Times staff writer Jonathan Kaiman and Yingzhi Yang in the Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.

MORE FROM WORLD:

Move by Rubio leaves U.S. without ambassador to Mexico

Class struggles play out, sometimes violently, on the beaches of Rio

Westerners in Beijing warned of Christmas terrorism threat; parts of city locked down

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.