South Sudan’s leaders got rich off war as their people suffered, report finds

Reporting from JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — It pays to commit war crimes, according to a report by an investigative group co-founded by actor George Clooney that spent two years scrutinizing the world’s newest country, South Sudan.

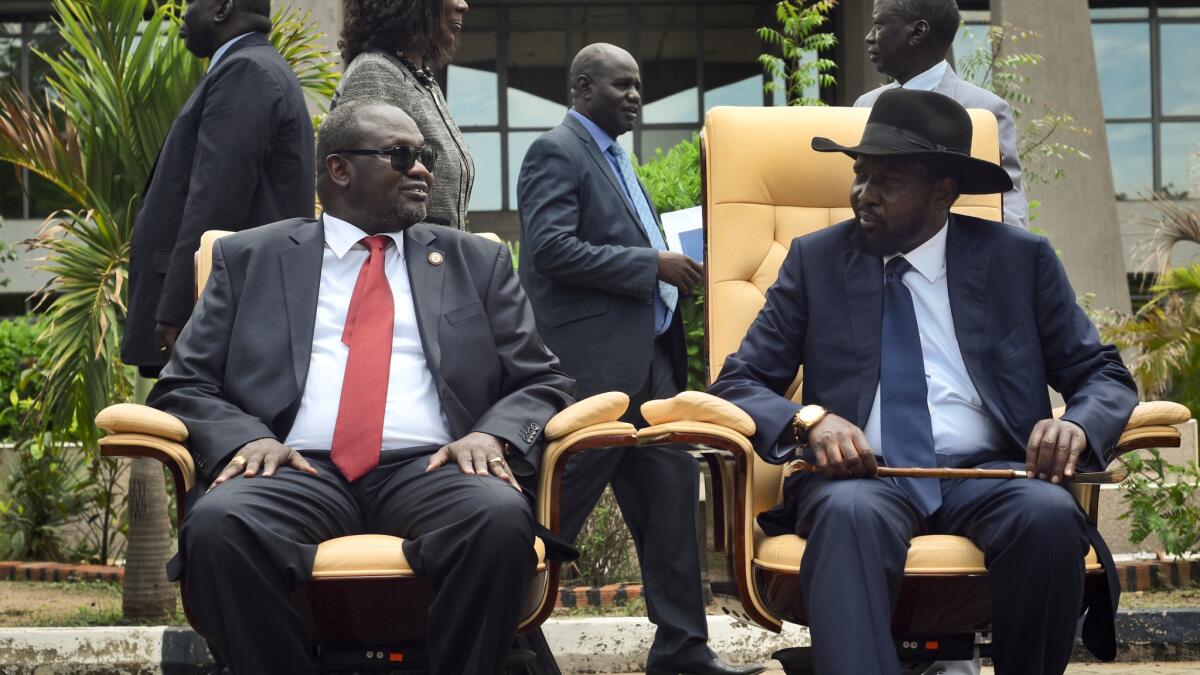

On the surface, the country’s brutal 2013 civil war was fought over ethnic divides. It grew out of a conflict between the president, Salva Kiir, a member of the Dinka ethnic group, and his then-deputy, Riek Machar, a member of the Nuer who was angling to succeed him.

But the Sentry, the group co-founded last year by Clooney and activist John Prendergast, contends that the conflict was really a struggle for power and control of state assets, such as oil. The authors of the report accuse the rivals of drumming up ethnic hatred to fuel the conflict, transforming the country into a violent kleptocracy.

South Sudan is one of the world’s least developed countries, heavily dependent on the international community for aid. But top officials got rich on war, the group alleges — and had little incentive to usher in peace as a result.

“The key catalyst of South Sudan’s civil war has been competition for the grand prize,” the report says, “control over state assets and the country’s abundant natural resources — between rival kleptocratic networks led by President Kiir and [former] Vice President Machar.”

“South Sudan’s top officials have benefited both financially and politically from the continuing war and atrocities committed within their country.”

South Sudanese officials have not yet responded to the report’s claims.

The group found that “top officials ultimately responsible for mass atrocities in South Sudan have at the same time managed to accumulate fortunes, despite modest government salaries.” Researchers scrutinized the assets of South Sudanese officials, relying on published information, interviews, social media postings and Google Earth images of properties owned by the officials.

Top officials and their families also own stakes in companies doing business in South Sudan, have stashed fortunes overseas, drive luxury cars and have bought multimillion-dollar mansions outside the country.

Kiir has a 12-year-old son who holds a 25% stake in a South Sudanese holding company formed in 2016, the researchers found. In all, seven of his children, his wife and his brother-in-law own stakes in two dozen companies operating in oil, mining, construction, gambling, banking, telecommunications, aviation, and government and military procurement in South Sudan.

Both Kiir and his rival, Machar, own luxurious homes outside South Sudan. Gen. Paul Malong, the military chief of staff, owns two houses in the Ugandan capital, Kampala, and a $2-million mansion in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, despite a government salary of $45,000 a year, the group found.

Another military official, Gen. Gabriel Jok Riak, has a Kampala property next door to Malong’s, while Gen. Malek Reuben Riak has a house a few miles away. Malong and Reuben Riak have held stakes in oil, mining and telecommunications companies.

The group also questioned payments made by foreign companies. One Kenyan bank processed payments to Gabriel Jok Riak after he was sanctioned by the United Nations in March 2015, and his assets were supposed to be frozen.

“Large financial transactions involving politically exposed persons, defined as senior government officials, judges, military officers, and senior executives of state-owned corporations, as well as their families, ought to raise red flags that those transactions, or the conduct that led to them, may have been unlawful or otherwise improper,” the report says. “Unexplained wealth such as this should be enough to provide authorities with a reasonable basis for investigating the sources of that wealth and whether any wrongdoing occurred.”

The report calls on the U.S. and other governments to take tougher steps to crack down on money laundering by South Sudanese officials.

The Sentry was launched last year to investigate how war is financed by state resources, including diamonds, minerals and oil. The South Sudan report is its first investigation.

After fighting started in the capital, Juba, in 2013, it swiftly spilled into brutal ethnic conflict in other parts of the country, particularly the north and east. Women and girls were gang-raped and forced into sex slavery. Men were shot on sight. Boys were castrated. Those couldn’t flee — babies, old people, the weak and sick — were burned alive in houses, according to reporting by the U.N. and human rights organizations.

Both sides were responsible for war crimes, according to the U.N. and human rights organizations that have reported on the atrocities.

The two sides signed a peace deal in August 2015 that was never implemented. A government of national unity was to be set up but fighting broke out in July, and Machar and many of his fighters fled the country.

The war led to a dire humanitarian crisis, with populations in Unity state in the northeast facing conditions close to famine last year as they fled with nothing but waterlily bulbs to survive on.

Close to a million people were driven from their homes, according to the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees and about 4.8 million people — 40% of the population — need emergency food aid, according to the World Food Program.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.