Appeal of Oscar Pistorius’ murder acquittal centers on intent to kill

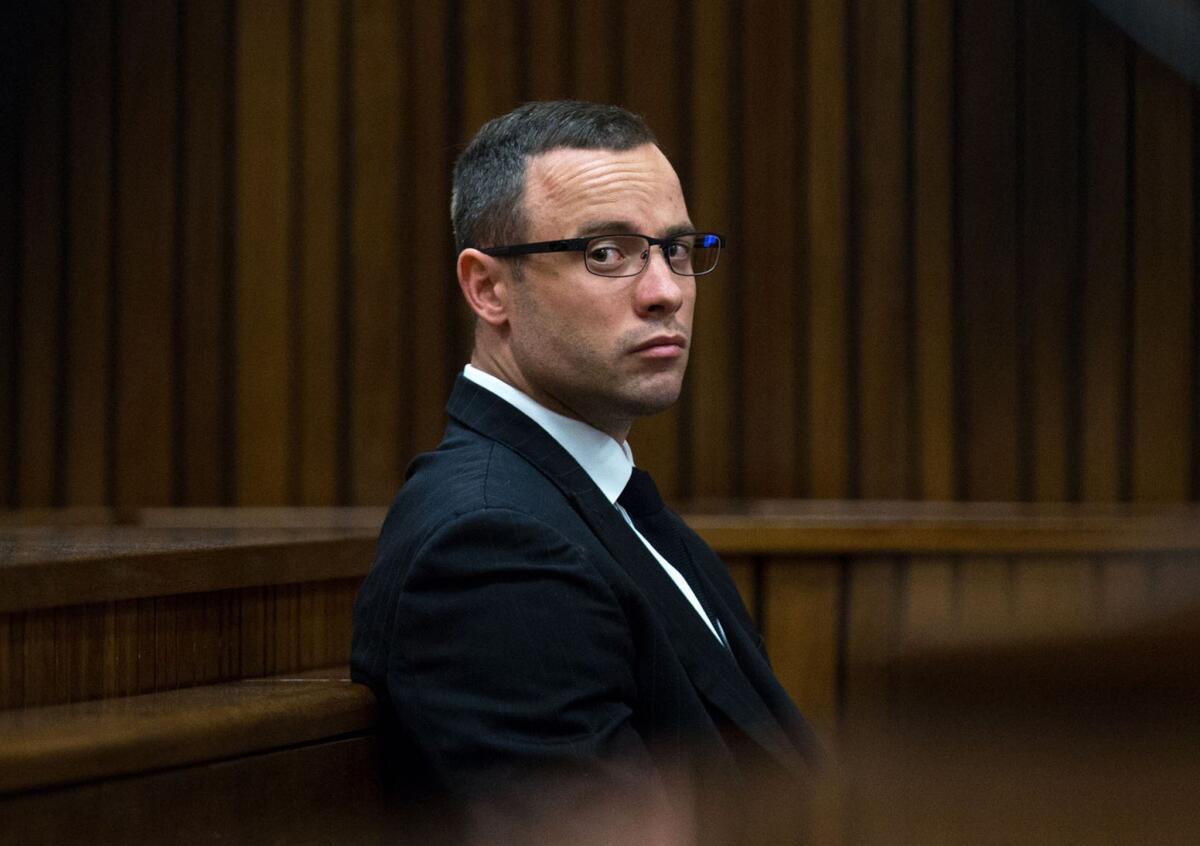

Oscar Pistorius sits in court on May 13, 2014, during his original trial in Pretoria, South Africa.

The emotion and drama of last year’s murder trial of South African athlete Oscar Pistorius were absent in the prosecution’s appeal to overturn his acquittal Tuesday. The athlete, who howled in anguish, vomited and repeatedly contradicted himself during his trial, wasn’t in court Tuesday.

Even the victim, Reeva Steenkamp, seemed strangely irrelevant in the Supreme Court of Appeal in Johannesburg, as prosecutor Gerrie Nel argued that it didn’t matter who Pistorius thought was behind a bathroom door when he opened fire in 2013.

The double amputee athlete was acquitted of murder in September 2014 but convicted of culpable homicide, or negligent killing, and sentenced to five years in prison. He was released last month and will serve the rest of the sentence confined to his uncle’s home in Pretoria, which could change if the prosecution wins its appeal and Pistorius is found guilty of murder or ordered to face another trial.

Pistorius fatally shot Steenkamp, his girlfriend, when he fired four hollow-point bullets through the door of the small toilet cubicle in his bathroom, later claiming he thought she was an intruder.

But the identity of the victim wasn’t important, Nel argued in the appeal. The main legal argument revolved around whether Pistorius intended to kill whoever was behind the door, even if there was no real danger to his life. Or did he genuinely believe his life was in danger and mistakenly think he was entitled to shoot?

The key question came down to this: Did Pistorius, a gun enthusiast familiar with weapons and ammunition, realize that firing four shots into the cubicle would probably kill the person inside?

Several of the five judges in South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal questioned the reasoning of trial judge, Thokozile Masipa, as they questioned Pistorius’ attorney, Barry Roux.

In South Africa, if a person foresees that his or her actions can kill someone — anyone — and proceeds anyway, it is murder, a principle known here as dolus eventualis, or indirect intent.

One appeal court judge, Justice Lorimer Leach, suggested that Masipa made a mistake when she analyzed the issue by failing to address whether Pistorius was aware that firing four bullets would kill anyone within the tiny cubicle.

“The issue was not whether Reeva was behind the door. The issue was [Pistorius] knew a person was in the cubicle. That to me is the primary difficulty that I have,” Leach said.

But Roux argued that the trial judge had looked at Pistorius’ fearful state of mind in her conclusion.

“There stands a man on stumps, he’s vulnerable, he’s extremely anxious. His version is that he believed his life was in danger and he discharged the shots,” Roux said.

Cape Town-based legal analyst William Booth said he believed Nel had the stronger case in the appeal, with Roux appearing to struggle to convince the judges that Pistorius really believed he was under attack.

“If you shoot four shots through a door into a tiny little toilet and you know there’s someone behind that door, surely you must know that some or all of the shots would strike the person behind the door and he could die by one or more of your shots, or by ricochet,” Booth said.

Booth said Masipa didn’t spell out her reasoning clearly enough and appeared to confuse the legal principles, leaving grounds for the prosecution to appeal.

“She didn’t put across very well why she came to the conclusion it wasn’t dolus eventualis and why it was culpable homicide.”

Leach said the toilet cubicle was so small that there was “no place to hide” from the shots, making it more likely Pistorius did foresee his actions would probably kill or injure the person within. He said that because the door never opened, Pistorius couldn’t have known whether there was a 12-year-old child or a man armed with a machine gun in the cubicle when he opened fire.

Roux contended it was not for the appeals court to overturn Masipa’s conclusion that Pistorius acted in fear for his life.

“If he did not hold a genuine belief, why would he have fired?” he asked. “Something must have happened in that man’s mind that caused him to fire and he explains this. We have this overly anxious person, incorrectly so, but that’s who he is.

“He’s really scared. He believes the deceased is in the bedroom, that’s the finding. One tries to sit back and think why did then this man fire the shots? It’s unfair then to impute him with no reason and say he’s guilty.”

Nel responded, “What remains is that he had foresight, he reconciled himself and he did shoot.”

He argued that Masipa ignored crucial circumstantial evidence and misapplied the law. “If the court took into account all the circumstantial evidence it would have rejected his version outright,” Nel said.

Legal expert James Grant, who advised the prosecution, said the law around dolus eventualis and self-defense needed clarification by the Supreme Court of Appeal because of inconsistent judgments over the years.

“There’s no question that this is going to be an important thing in clarifying those issues,” he said.

The appeal court adjourned and reserved its finding. A decision could take weeks or months.

ALSO

In Damascus, Syrians express a surprising level of optimism

A forgotten war in the Middle East takes its toll on civilians

In Russia, conflicting theories over passenger jet crash in Sinai

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.