A 40% price cut hasn’t helped Uber in Africa’s biggest economy

Reporting from Lagos, Nigeria — For the past two years, Frederick Aguinede has spent most of his time behind the wheels of cars he will never own. He wakes before dawn, turns on his Uber app and doesn’t return to his apartment until long after dusk — usually clocking more than 12 hours on the road each day.

On paper, it looks like he takes home upwards of $280 a week.

But only a handful of that cash really belongs to him: Uber takes 25% of earnings from its drivers, and between rental fees he pays the car owner, plus gas and tolls, the 29-year-old has been pocketing less than $10 a day.

Then Uber, in a bid to remain competitive in a market that was seeing a growing number of cheap rides, cut its prices by 40%.

Aguinede’s livelihood went from tough to nearly unmanageable. “After the price slash, it was difficult to meet the target for the owner of the car,” he said. “If I had kids, it would be impossible.”

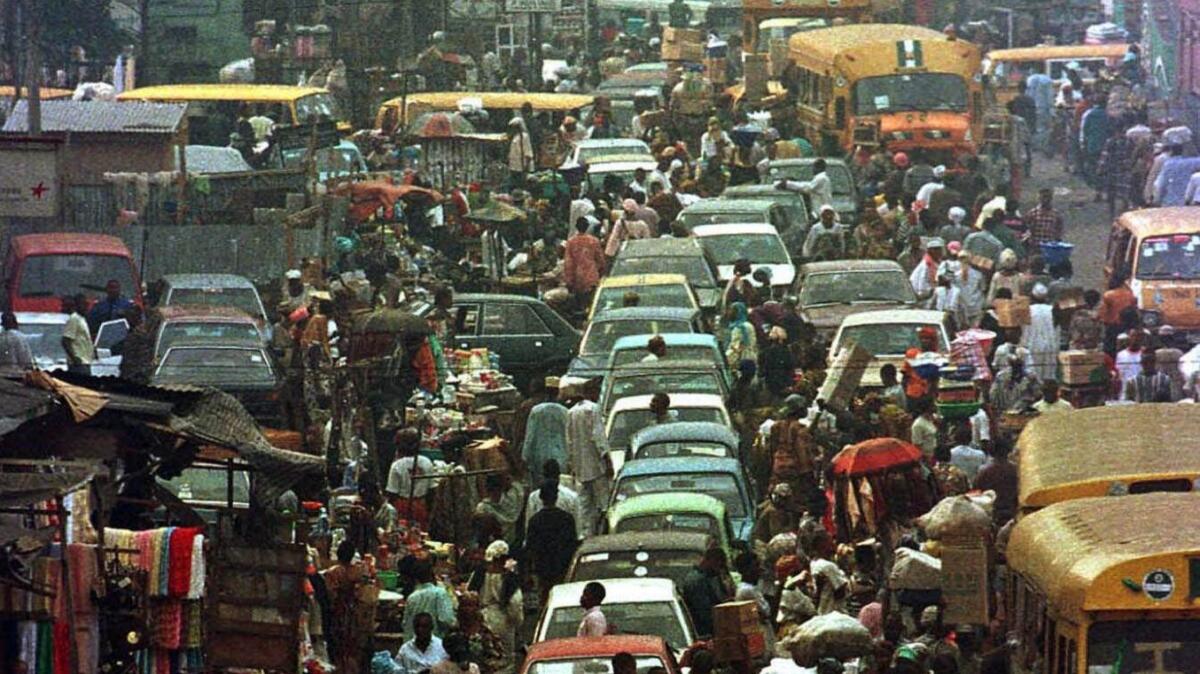

Aguinede is one in a flood of drivers here who bailed on Uber altogether. The San Francisco-based ride-sharing company launched in Nigeria in 2014, and Lagos certainly seemed like a good place to start. The megacity is home to 22 million people, including a large number of young, wealthy urbanites eager for an alternative to public transit or expensive private car hires.

Over the past year, the company has faced a barrage of criticism after a series of high-profile, embarrassing incidents, including a leaked dashcam video of then-CEO Travis Kalanick screaming at a driver over price cuts and a Justice Department probe into a secret Uber program that allowed the company to operate in cities where it had been banned.

Its movement into cities around the globe has been slowed by challenges from local taxi companies, competing government subsidies and prohibitive regulations.

Uber’s expansion to Africa is presenting its own challenges. After the 40% price slash took effect in Nigeria in May, drivers took to the streets in protest. Then, using WhatsApp, they organized hundreds of others to switch to Estonian app Taxify, one of Uber’s main competitors in Nigeria. Taxify launched here in November 2016 and takes only a 15% commission from its drivers, compared to Uber’s 25%.

Aguinede is one of the Nigerians who helped organize that exodus, and the impact was immediate. Over the course of a few days, as drivers peeled away from Uber in protest, wait times for customers in Lagos surged. Aguinede said drivers began encouraging each other to strike up conversations with other drivers in traffic to urge them to switch to Taxify too. Soon, customers had to follow suit.

In an email, Francesca Uriri, a spokesperson for Uber in West Africa, said that Uber lowered its prices last spring to stimulate business for its drivers and insisted she is “confident that driver-partners have no need to fear lower earnings.”

But several drivers interviewed by the Los Angeles Times claim they never received top-up payments that the company promised would make up the difference from price cuts. She said drivers were informed they would qualify for that additional payment only if they completed one trip every two hours and accepted 80% of requests that came their way.

Muktar Lamidi drove for Uber for over a year and was shocked when the company suddenly lowered its prices last spring. So he contacted an Uber employee to demand an explanation. “They said anybody who doesn’t want to do it anymore should just go,” he said. “That was their answer.” So Lamidi switched to Taxify.

The mass retreat from Uber earlier this year is just one piece of a growing backlash against the company in Nigeria. In November, Uber acknowledged its drivers were using a GPS app that allowed them to falsify routes and charge passengers higher rates for their trips — allegedly a reaction to the low prices. Earlier in the month, some drivers in Lagos launched a class-action suit against Uber, demanding to be recognized as employees rather than independent contractors. In Nairobi, Kenya, and Kampala, Uganda, Uber drivers are complaining that the company’s rates do not take local economic conditions into account. Taxify launched in Kampala in October, introducing new competition to that market.

In Lagos, Taxify sees its business as a response to a visible need for competition in a place where Uber previously held the monopoly.

“It’s a situation where the market needed an alternative, and the drivers needed an alternative,” said Terver Bendega, brand manager for Taxify in Nigeria. She said that while Taxify has some part-time drivers, the majority are doing it as their full-time job. “They’re fathers, they’re husbands, they’re breadwinners, they’re real people, and we want to treat them like people,” she said.

Regardless of which app drivers are using, the economics of private car share in Nigeria is punishing. Most drivers can’t afford to own their vehicles, meaning they pay the majority of their income back to the owner of their car. Multiple drivers said in interviews that they live in fear of owners taking the cars away.

“You depend on him for the car,” Aguinede said of the man who owns his vehicle. “There’s no job out there. You just have to do anything to keep the car to yourself.”

Dominic, a driver who requested his last name not be used over concerns he would face backlash from his car’s owner, switched from Uber to Taxify in January. He started working as a driver after he lost his office job and failed to find other work.

He was forced to sell his personal car to make ends meet for his three children under the age of 10. Now, he pays the car owner around $165 a week to drive on ride-sharing apps. The rental cost is so high, Dominic said, that between gas and tolls, he often doesn’t break even. But like Aguinede, he will do what it takes to keep the car, even if it means driving upwards of 20 hours a day and catching just a few hours of sleep.

“This is the nature of the country, that no one is willing to stay at home [and not work],” he said. “If I said, ‘Let me go drop the car because the market is not there,’ then at the end of the day, I will be suffering myself and the kids at home will suffer too.”

Over the last few months, Uber has held town hall meetings with its drivers to address grievances over issues including traffic and fares. Since then, Uber introduced a new feature in the app that allows drivers to earn while they wait for riders, and in November, the company increased fares in Lagos by 20%.

“We want to show we are indeed listening and we want to ensure that drivers earn a respectable income from partnering with Uber,” Uriri said. Still, Uber and Taxify remain in fierce competition in the ride-share market here, and many drivers claim their priority is driving for the app that takes the least amount of commission.

In any case, drivers are keenly aware that, in a tough economy that is only Ijust emerging from a recession, there are plenty of unemployed people who would be happy to take a driver’s place.

Aguinede, for example, has a university degree in philosophy. But after he couldn’t find funding to pursue a doctoral program, he went to a staffing agency in Lagos to try to find work. The recruiters told him they had plenty of jobs available but had only two questions for him: How well could he navigate Lagos, and did he know how to drive? The only positions they actually had, Aguinede realized, were driving Uber for wealthy car owners. He was willing to take what he could get.

“Nigeria is such a difficult place,” Aguinede said. “Over time, you start changing your dreams and aspirations.”

UPDATES:

Dec. 6, 9:33 a.m.: The article was updated to reflect Uber’s latest town hall meetings with drivers and a 20% fare increase.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.