Mali attack latest to rattle global security: The deadly hotel siege underscores a broader threat

reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — From cafes in Paris to the teeming markets of Nigeria, in tourist resorts on the Sinai peninsula and now a glitzy hotel in the dusty capital of Mali, the message Islamist terrorists sent to the world over the last several weeks is that no one — almost anywhere — is safe.

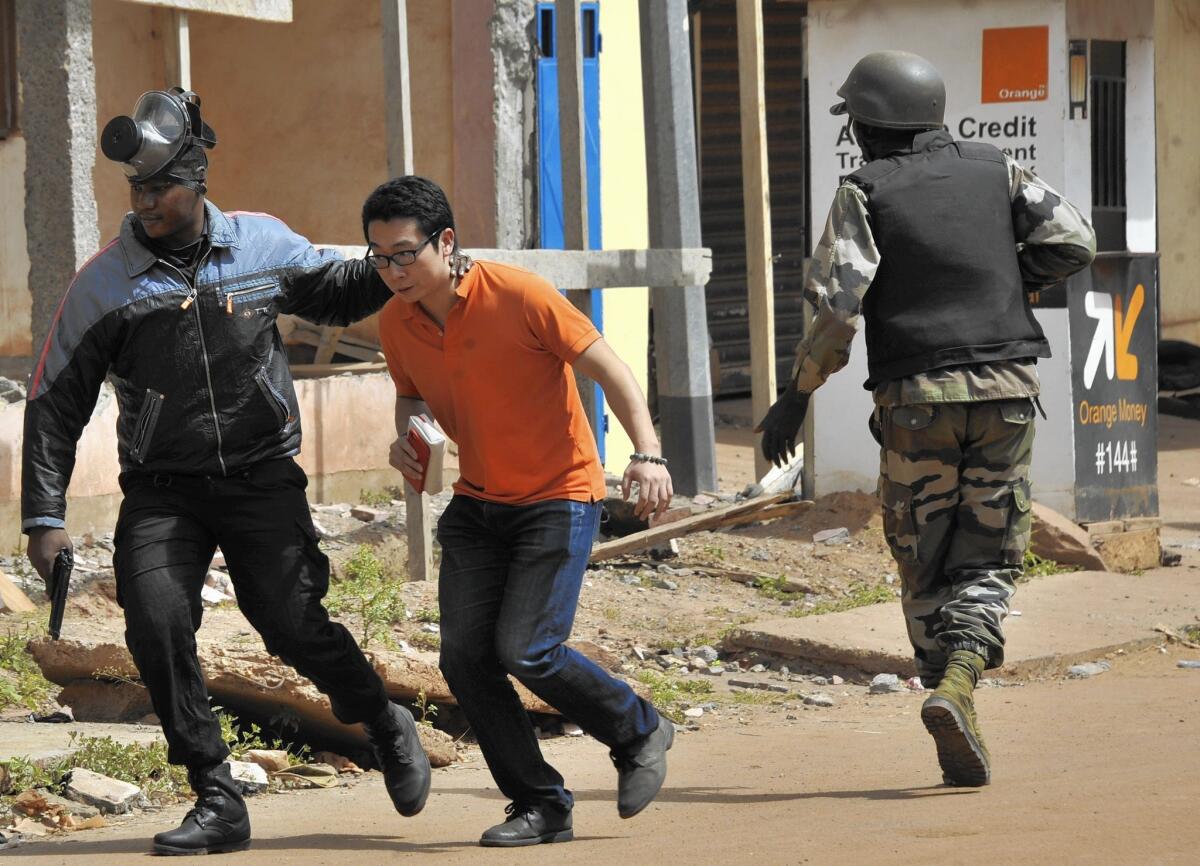

The attack Friday, in which armed gunmen stormed the Radisson Blu Hotel in Bamako and swept through the rooms, leaving an estimated 20 people dead, targeted a key region of French anti-terrorism operations in Africa only a week after Islamist attackers launched a wave of shootings and bombings across Paris.

The attacks in Paris, for which the militant group Islamic State claimed responsibility, seemed to signal a sharp escalation of the Syrian-based organization’s ability to project lethal mayhem far outside the Middle East, particularly when combined with the bombing last month of a Russian passenger jet over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula — an attack that also is being linked to Islamic State.

But Friday’s attack in Mali underscored that Islamic State’s rival Al Qaeda and its affiliates remain a serious threat. A group led by Al Qaeda’s most notorious leader in northern Africa, Algerian militant Mokhtar Belmokhtar, claimed responsibility for the deadly hotel assault.

Belmokhtar, who leads a group of Tuaregs and Arabs known as Al Murabitoun, is a staunch Al Qaeda loyalist who has denounced Islamic State for dividing Muslim militants. He led a 2013 operation in Algeria in which militants laid siege to a gas facility in the eastern Algeria city of Ajdabiya, an operation that included taking 800 hostages and killing 39 foreigners, including three Americans and six Britons.

Friday’s attack on the hotel appeared targeted at French interests, with France the standout Western military power in West Africa fighting Islamist terrorist groups. Malian militant groups loyal to both Islamic State and Al Qaeda have called for continued attacks on France and French interests in Africa and elsewhere.

The hotel attack, signaling a dangerous surge in anti-Western radicalism in west and northern Africa, comes amid a deteriorating security situation in Mali, with Islamist militant groups from the north increasingly infiltrating the south of the country to launch attacks.

It also highlights growing concerns that Islamic State is sending envoys deep into West Africa to try to entice more militants to carry its flag, after it successfully recruited the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram under its umbrella in March. Yet Al Qaeda has retained a strong presence in Africa, with the loyalty of groups in Mali, Somalia and elsewhere.

As is apparent in this dangerous new world, militants — whatever their loyalties or how extensive their international connections — don’t require sophisticated weapons or even particularly complex planning to wreak maximum damage. The attacks in Paris and Mali alike were perpetrated by a handful of people wielding automatic weapons and in some cases explosives, targeting vulnerable, lightly guarded civilian facilities, and exhibiting a willingness to die carrying out their operations.

The model was popularized by terrorist groups in Africa, notably in the 2013 Westgate mall attack, carried out in Nairobi, Kenya, by four attackers from the Al Qaeda-linked Somali terrorist group the Shabab, which claimed 67 lives. Likewise, a Shabab attack on Garissa University College in northern Kenya in March was carried out by a handful of gunmen. It killed 148, mainly students.

Western interests in African countries with home-grown terrorist groups, including Kenya, Mali, Somalia and Nigeria, face a heightened risk, security analysts say, given high levels of corruption in police and security services, intelligence failures and lack of coordination between different wings of the security forces.

One of the key threats to the West with the continuing violence in Africa, terrorism analysts say, is that extremist allies of Islamic State, such as Boko Haram, may embrace the global warfare of Islamic State and turn their attention to attacks on Western targets. Boko Haram has so far focused on attacks on Nigerian targets — initially, attacks on Nigerian security forces, but increasingly, its targets have been civilians, including children.

“To date, they have not shown themselves to be a direct threat to Western countries. But I wouldn’t rule it out in future,” J. Peter Pham, director of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council, said of Boko Haram. “It has evolved very quickly. That they haven’t attacked foreign targets doesn’t mean they don’t have that ambition or couldn’t evolve a strategy.”

One key ideological difference between Al Qaeda affiliates and Islamic State loyalists in Africa is that gunmen from Al Qaeda-linked groups often call on victims to prove they’re Muslim, by reciting Koranic verses or the Shahada, a profession of Islamic belief, or by answering questions proving their knowledge of Islam, before setting those victims free.

Islamic State, on the other hand, sees all those who don’t embrace its violent vision of Islam, including Muslims, as infidels who must be slaughtered. It has threatened more attacks on France, Russia, the U.S. and other countries involved in airstrikes in Syria and Iraq against the group, and was responsible for killing 6,073 people last year, according to the Global Terrorism Index released this week by the Institute for Economics and Peace.

Secretary of State John F. Kerry said Thursday the U.S. had succeeded in neutralizing Al Qaeda as an effective force, and would neutralize Islamic State even more quickly.

But Bill Roggio, author of the blog the Long War Journal, about the global war on terrorism, said Al Qaeda remained dangerous.

“I would argue that Al Qaeda is as great a threat as it was the day before 9/11. Today, it’s running insurgencies in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, Mali, Egypt. ... We can go on and on. When you put all that together, it’s impossible to come to the conclusion that Al Qaeda has been neutralized,” he said.

“They want to kill French. They want to kill Americans. It’s part of their strategy to get everyone out of the country so they can get control,” he said, referring to Friday’s attack.

He said there was a risk that rivalry between Islamic State and Al Qaeda could see each vying for recruits and finances by mounting increasingly spectacular and violent operations.

Islamic State, with its expansionist ideology, has won the loyalty of African militants in Libya, Mali, the Sinai Peninsula, Algeria and northeastern Nigeria, where Boko Haram may have killed even more people than Islamic State did last year. A Malian terrorist group, the Movement for Justice and Unity in West Africa, reportedly declared allegiance to Islamic State in May, prompting Belmokhtar to declare his continued loyalty to Al Qaeda.

Pham said Islamic State’s absolutist ideology and ambition to be a global Islamic empire has left little realistic opportunity to negotiate with the group — or its affiliates.

“With that type of ideological absolutism where they’re aspiring to be a universal empire of religion, there’s no compromise possible,” said Pham. “And Boko Haram is evolving the same ideology. Perhaps earlier in its history, when [Boko Haram] was primarily a local concern and its ideology was not as rigid in its adherence to absolutism, perhaps there might have been a possibility of compromise. But that moment has gone by.”

In recent months, Malian militant groups have switched focus from attacks on military targets in the north to threaten civilian targets in central and southern Mali. The country has seen several deadly attacks this year, including an attack on a restaurant in March that left five dead, including two French, a Belgian and two Malians, also claimed by Belmokhtar’s group.

France intervened in Mali in 2013 after Al Qaeda-linked militias, AQIM, MUJAO and Ansar Dine, seized more than half the country and imposed a harsh form of Islamic law. France saw the conquests as a direct threat to Europe, giving terrorist groups a stronghold within easy striking distance.

France’s military action, Operation Serval, with 4,500 troops on the ground, killed several militant leaders, leaving Belmokhtar as the predominant Al Qaeda leader in the region. But it has since scaled back operations, with 3,000 personnel covering Mali and four other countries.

ALSO

16-year-old charged with murder in Downey police officer’s killing

Sharp divisions emerge on campuses as some criticize activists’ tactics as intimidation

Massive El Nino gaines strength and is likely to drench a key California drought zone

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.