Kenya is pulling welcome mat on 600,000 refugees, triggering fear of another mass migration

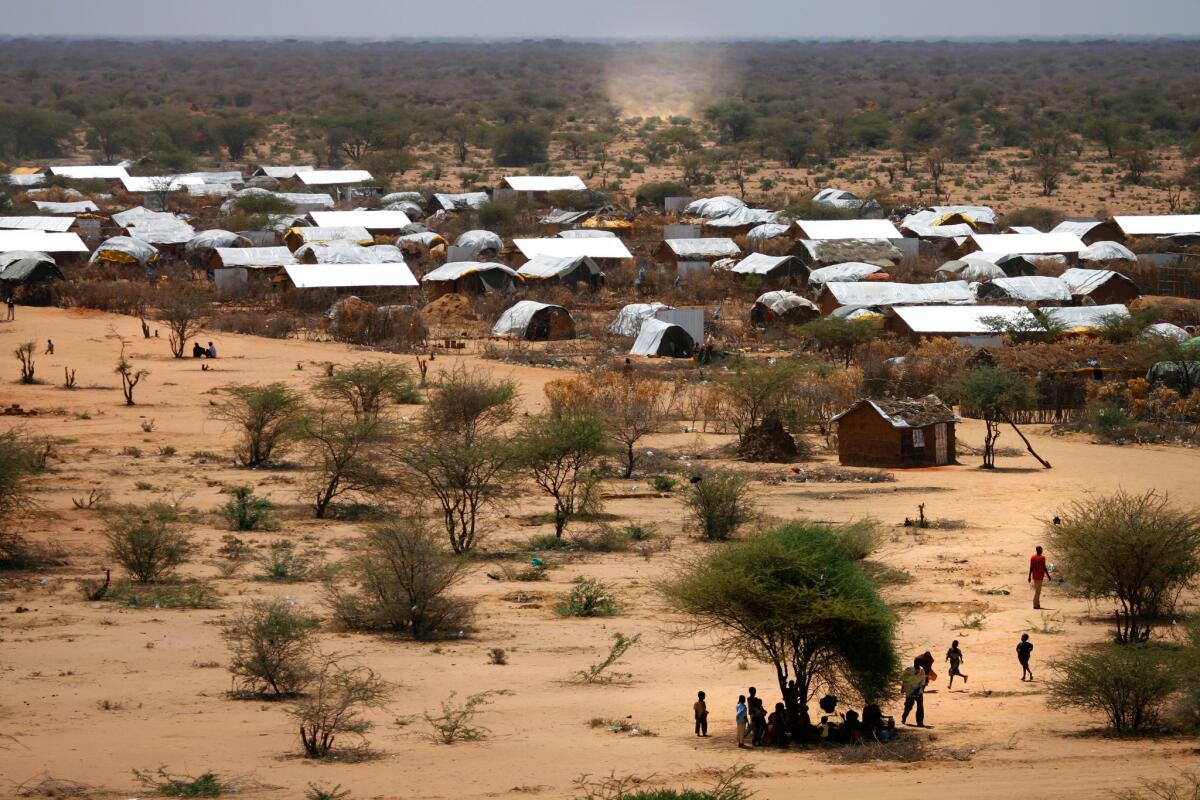

Makeshift homes for refugees irrationally occupy the harsh landscape at the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya’s North Eastern province.

Kenya’s vow that it will shut down its refugee camps, home to as many as 600,000 people, has triggered global concern that another mass exodus of people is about to take shape, similar to the ongoing migrant crisis in Europe.

The plan to empty out the camps, which include the world’s largest refugee complex, is prompting unease that the East African nation might be taking its lead from Europe, where there has been widespread rejection of those seeking safety.

It also raises the question of whether Kenya might be justified in demanding that the international community provide more assistance for the migrants.

The camps, which have existed for a quarter of a century, were never meant to be more than temporary way stations for those fleeing their homeland, and Kenya now is citing security concerns, financial challenges and environmental burdens for closing the Dadaab and Kakuma camps. Dadaab is the largest refugee facility in the world, with at least 330,000 residents.

It is not the first time that authorities have threatened to shutter the camps, but this time the government seems to be resolute, disbanding its Department of Refugee Affairs, according to a statement issued by the country’s principal secretary of the interior.

Can Kenya actually close the camps? Do refugees have rights?

Generally, refugees are displaced people who have been admitted to a country because they are unable or unwilling to return to their homeland for reasons such as war, natural disaster or fear of persecution.

Hannah Garry, a law professor and director of the International Human Rights Clinic at USC, said that by closing the camps, Kenya would be violating treaties it has signed, including the 1951 Refugee Convention, a United Nations multilateral treaty that defines who is a refugee, refugee rights and the responsibilities of nations that grant asylum.

In 2009, newly arriving refugees, mostly Somalis, crowd into a line to be admitted into Dadaab, the largest refugee camp in the world.

“People have fled over the last several decades and have sought asylum,” Garry said. “Once they have been given the status of refugees in a host country, they have the right to stay until the situation back at home has changed.”

That is certainly not the case for many of the region’s conflict-ridden nations. Last month, for example, the Office of U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees reported that Kakuma had recorded a steady increase in new arrivals from South Sudan, up from an average of 100 people a month at the start of this year to 350 a week the last two months.

About 2.3 million people have had to flee their homes since violence broke out in South Sudan in December 2013, according to the U.N., with 678,000 of them crossing into other countries as refugees.

So why would Kenyan authorities take such extreme action?

Kenya’s authorities have argued that refugee camps are a breeding ground for the Shabab, a Somali terrorist group with links to Al Qaeda. Last year, Shabab militants stormed a university in the country’s northeast, killing at least 147 people. Two years before that, the extremists slaughtered at least 67 people in an attack on an upscale shopping center in Nairobi, the capital.

“They are casting blame particularly on the Somali refugee community as the cause of Kenyan insecurity,” said Leslie Lefkow, deputy director for the African division of Human Rights Watch. “But there is no evidence the Somalis refugees are responsible for the attacks in Kenya. There have been no prosecutions. This is scapegoating, that the Kenyan government has been using repeatedly.”

Garry said Kenyan authorities should do more to properly screen people to determine who might be a terrorist and then take the necessary action.

“They can’t just send hundreds of thousands of people back for fear that maybe one of them might have a link to terrorism,” Garry said.

Advocates for refugee rights also believe that Kenya might be playing off the dynamic of the negative reaction Europe has had toward the mass migration of predominantly Syrian refugees to its shores. Several European nations have refused to resettle refugees or shown scant enthusiasm to accept them.

Migrants and refugees stay on train tracks as Greek police try to persuade them to leave the railroad in the makeshift camp at the Greek-Macedonian border near the village of Idomeni on April 18, 2016.

“The failure of European countries to live up to their obligations has provided Kenya with ballast to negotiate,” said Lefkow, who spoke via Skype from Amsterdam. Kenya “could be making this gesture in an effort to drum up more funds,” she said.

Who lives at the camps and what is life like there?

About two-thirds of the refugees and asylum seekers in Kenya have fled conflict elsewhere, and they’ve been arriving since the 1990s, according to the U.N. The vast majority are from Somalia, followed by South Sudan and Ethiopia. Smaller numbers have come from Burundi, Uganda, Rwanda, Eritrea, Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Dadaab is in eastern Kenya, about 50 miles from the border with Somalia, and Kakuma about 80 miles from the Sudanese border. Both camps are sprawling, dusty, fly-infested settlements of tents, mud huts and makeshift homes offering few basic comforts, such as indoor plumbing.

“It’s a miserable existence, and no one would seek to extend people’s lives there indefinitely unless the alternative is worse,” Lefkow said.

Refugees gather at one of Dadaab’s water points to collect water for cooking and drinking, but there is an insufficient supply to properly accommodate every person living there.

What would be the consequences if the camps closed?

It could create an unprecedented asylum crisis for the refugees, many of whom cannot return to their homelands, said Heather Amstutz, the Nairobi-based regional director for the Horn of Africa for the Danish Refugee Council.

“Specific groups such as child-headed families would be particularly vulnerable,” she said in an email.

Hundreds, if not thousands, of refugees have been born in the Kenyan camps and lack any experience of their family’s homeland.

Refugees await entrance into Dadaab in 2009.

The effect on regional nations would also be disastrous, Amstutz said, because countries neighboring Kenya are already shouldering a huge influx of refugees. For example, Ethiopia hosts more than 730,000 refugees, Uganda about 477,000 and Tanzania more than 300,000, according to data from the Danish aid group.

“We must not forget that situation in Somalia remains highly volatile and fragile as a result of continuing insecurity and the impact of recent severe drought, while South Sudan is in the midst of a civil war,” Amstutz said.

If banished from the camps, some refugees might try to relocate to urban areas, but with few resources and little support such an option would probably be devastating, Amstutz said.

“It’s a horrific scenario,” Lefkow said.

For more news on global sustainability, go to our Global Development Watch page.

And follow me on Twitter: @AMSimmons1

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.