For Ari Huffman, the case for divesting from Israel is clear-cut — at least morally.

The UC Merced student doesn’t understand exactly how university endowments work. But as Israel continues its relentless bombardment of the Gaza Strip, she knows she doesn’t want her tuition fees funding a war that has killed more than 35,000 Palestinians.

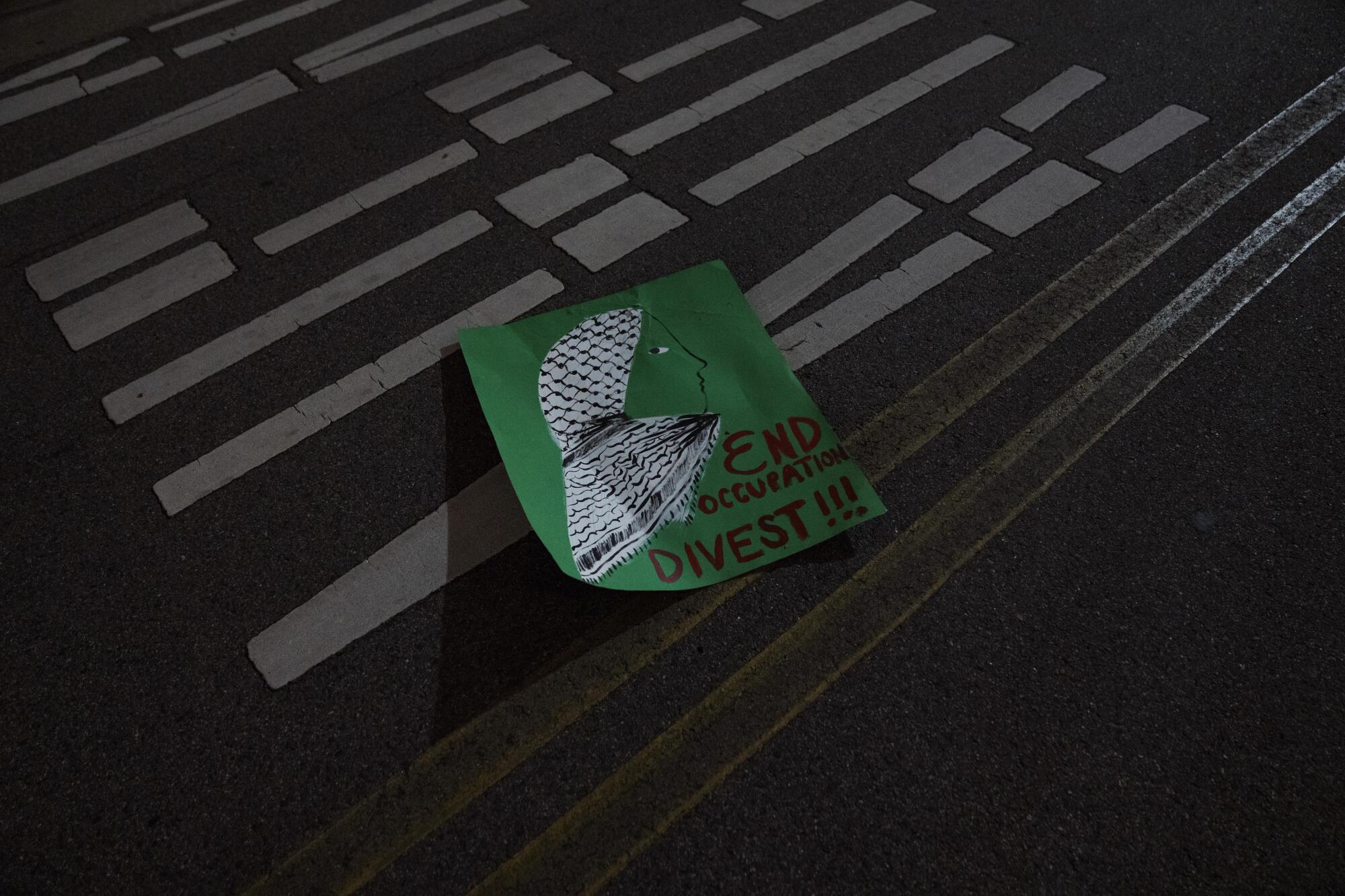

“I don’t want to be complicit,” she said after the UC Board of Regents wrapped up a three-day meeting with student activists on her campus. Huffman, a member of Students for Justice in Palestine, welcomed five UC regents to her school’s Gaza solidarity encampment last week for a meeting to discuss withdrawing funds from companies with ties to Israel.

The University of California system has stated it will not divest from Israel. But one of its 26 regents told the activists he supported their goals.

He warned, however, that it would be a long and difficult process, even if they could win over his fellow board members: 18% of UC’s $175 billion in investments is indirectly tied to Israel, including $3.3 billion invested in weapons manufacturers and $12 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds.

“The obstacles of the current investments are that some of them are in a timed agreement. You can’t just pull out,” Regent Jose Hernandez told activists.

“Understand it’s hard — not impossible — but it has to take time to divest,” he said.

Ever since the Israel-Hamas war began last year, student protesters chanting, “Disclose! Divest!” from California to New York have vowed they “will not rest” until university administrators agree to their demands. But administrators say it is not so easy.

Colleges have long resisted calls to divest, noting that such a move would be logistically complicated, morally tricky and politically divisive, and could open them up to fiduciary risks and legal challenges.

“Let’s recognize that bringing morality into economics is hard,” said Luigi Zingales, a University of Chicago professor of entrepreneurship and finance.

A substantial number of Jewish students, faculty, alumni and donors say that boycotts and divestment campaigns unfairly target Israel. And in recent years, 38 states, including California, have adopted laws or executive orders designed to discourage boycotts of Israel.

Many university administrators and financial experts note that untangling endowment funds from Israel would take time and involve potential loss of money that helps subsidize student tuition, faculty salaries and critical research.

“When you’re talking about a country with which the United States has such multiple and deep relationships, it would be quite difficult to identify everything that is connected to Israel,” said Nicholas Dirks, former chancellor of UC Berkeley. “Even if a board said, ‘Yes, we want to disinvest,’ I think it would be complex to identify and then very, very slow to enact without there being financial consequences.”

::

The campaign to punish Israel economically dates to long before Oct. 7.

In 2005, a coalition of Palestinian groups — inspired by the 1980s boycott of South African apartheid — called for an international campaign of boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel.

Their goal: to divest until Israel ended its “occupation and colonization of all Arab lands,” recognized the equal rights of “Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel,” and allowed Palestinian refugees to return to their ancestral homes.

The Anti-Defamation League claims the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement’s founding goals are antisemitic, because they “reject or ignore the Jewish people’s right of self-determination” and “if implemented, would result in the eradication of the world’s only Jewish state.”

Nearly 20 years later, many critics ask: What is students’ end goal? A cease-fire that will put an immediate stop to the current violence? The fall of Israel’s right-wing government? A one-state solution? The demise of Israel?

Students’ demands vary from campus to campus.

UC protesters are urging the university system to withdraw investment assets from companies “profiting from the Israeli occupation, apartheid, and genocide of the Palestinian people.”

At Columbia, they are pushing to divest from any company that funds “the perpetuation of Israeli apartheid and war crimes” — a broad net they say ensnares Google, which contracts with Israel’s government to develop cloud infrastructure, and Airbnb, which allows listings in Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

At Cornell, the focus is on weapons manufacturers, such as Boeing and Northrop Grumman.

Some universities have ruled out any divestment from Israel. The University of Michigan’s Board of Regents reaffirmed “its longstanding policy to shield the endowment from political pressures and base investment decisions on financial factors such as risk and return.”

But there are signs that pro-Palestinian activists are gaining momentum.

Brown University agreed to invite activists to present their arguments to divest the Ivy League institution‘s $6.6-billion endowment from companies that “facilitate the Israeli occupation of Palestinian Territory” before holding a vote in October.

Over the last few weeks, institutions including Harvard University and Northwestern University have struck deals: Protesters agreed to dismantle camps in exchange for administrators’ commitment to answer questions about endowments or reconsider the schools’ investment in Israel. Columbia University’s president said it will not divest from Israel, but offered to expedite its timeline to review new proposals from students.

Some institutions, such as UC Berkeley, have ruled out broad divestment from Israel but pledged to consider withdrawing from “a targeted list of companies due to their participation in weapons manufacturing, mass incarceration and/or surveillance.”

::

Financial experts say activists tend to misunderstand how endowments work.

“No student tuition is going towards the endowment,” said Gary Sernovitz, an executive at a private equity firm and author of “The Counting House,” a novel focusing on the chief investment officer of a prestigious university. “The endowment is used to subsidize student tuition that doesn’t fully cover the cost of an education in a modern university.”

The logistics of divesting depend on what students are demanding and how the endowment is set up.

“Divesting from publicly traded companies that are associated with Israel is relatively easy,” said Zingales, the University of Chicago professor. “If you are involving the private equity and venture capital component — a big component of the portfolio of every endowment — that is much more complicated. In fact, doing it immediately is impossible.”

The vast majority of universities hire third-party external investment companies to manage their endowments and give them broad mandates to make decisions, said Kevin Maloney, a professor of finance at Bryant University.

Typically, he said, endowment money is allocated to three groups: an index fund tethered to something like the S&P 500, which makes divesting from individual companies a challenge for managers running the same mandate for multiple clients; active managers of commingled trusts, which makes it hard for one client to impose a restriction on everyone else; and hedge funds that trade in long and short securities and are wary of transparency because they don’t want competitors to mimic their trades.

Some investment committees, Maloney said, are loath to give in to demands because they think of it as a slippery slope.

“The more constraints you put on the process, the harder it is to generate investment performance,” he said. “It goes against what they view as their fundamental mission.”

Still, some financial experts note that universities have divested in the past. Why, they ask, is Israel the exception?

“It’s a bit arbitrary to say we should stop at divesting from oil and private prisons, but not Israel, because Israel is too complicated,” Zingales said.

Activists point out that during the 1980s, students successfully pressured colleges to cut their financial ties to South Africa over apartheid — a system they argue has parallels with Israel.

Financial experts, however, note that endowments have changed massively in the nearly 40 years since universities divested from South Africa. Back then, Maloney said, there wasn’t as much private equity and hedge funds weren’t as ubiquitous.

And even if universities can agree that it is logistically possible to divest from Israel, some question whether boycotts have a practical effect.

In the 1990s, UC economists studied the effects of the 1980s boycott movement against South Africa and found “little discernible effect” on South African financial markets or the valuation of banks and companies with South African operations.

“Despite the public significance of the boycott and the multitude of divesting companies,” they argued, “financial markets seem to have perceived the boycott to be merely a ‘sideshow.’”

In recent years, some colleges have divested from private prisons, tobacco firms and fossil fuels. Four years ago, UC became the nation’s largest educational system to ditch its portfolio of fossil fuels and invest in wind and solar power.

But UC’s chief investment officer, Jagdeep Singh Bachher, noted that it dumped fossil fuels primarily because they determined renewable energy was more profitable — not because it was more moral.

“We believe,” Bachher and a colleague wrote in 2019, “hanging on to fossil fuel assets is a financial risk.”

::

If universities decide to bring ethical considerations into financial decisions, Zingales said, they must ask difficult questions. Is an association with weapons manufacturers worth tuition discounts? If there’s disagreement within the campus community, such as how Israel goes about defending itself, how do they decide?

“Ethical” investment doesn’t always involve a straightforward choice between good and evil.

“If the endowment doesn’t make as much profit, then it can harm the mission of the school,” Sernovitz said. “That can result in less funding for scholarships or medical research.”

At the heart of the conflict over Israel are fundamental disagreements about the nature of the war. Activists accuse Israel of perpetrating a genocide, but Israel and its supporters deny that charge, arguing its assault on Gaza is an act of self-defense, under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.

With widespread disagreement on campus, some institutions, like Columbia, have argued that divestment from Israel is a political position that does not have “broad consensus” on campus, a nod to the fact that many Jewish students, faculty, alumni and donors question singling out Israel.

UC maintains that divesting from Israel or taking part in academic and cultural boycotts would go against students’ and faculty’s “academic freedom” and the “unfettered exchange of ideas on our campuses.”

Many Jewish students, faculty and donors question why Israel is singled out.

“Many, perhaps most, Jewish people view BDS against Israel as a double standard,” said Mark Yudof, a law professor at Berkeley and former president of UC, using an abbreviation for “boycott, divestment and sanctions.” “Russia, China, Venezuela, Iran and other countries get a pass; Israel, the only Jewish state, gets all of the attention on campuses. ... It makes us suspicious that it’s either antisemitism or just a pure form of anti-Zionism.”

Those who push for divestment say they focus on Israel — rather than Russia, China or North Korea — because of its special relationship with the U.S.

“If the United States had the same kind of relationship with China, where it was giving it billions of dollars a year and vetoing things in the United Nations and supporting atrocities, we would obviously say the same thing,” said Jess Ghannam, a professor of psychiatry at UC San Francisco who is an activist with the UC Palestinian Solidarity Collective.

For one college president who agreed with students, the political repercussions were severe.

Last week, Sonoma State University President Ming-Tung “Mike” Lee came under criticism from Jewish students and alumni after cutting a deal with Students for Justice in Palestine to pursue divestment and an academic boycott of Israeli universities. “None of us should be on the sidelines when human beings are subject to mass killing and destruction,” he said.

Within 24 hours, Lee was placed on administrative leave. California State University Chancellor Mildred García accused him of “insubordination.”

Lee apologized. “In my attempt to find agreement with one group of students, I marginalized other members of our student population and community.”

By Thursday, Lee had retired.

::

Amid fierce disagreement, there is one thing experts seem to agree on: Universities should encourage vigorous discussion of the financial, moral and political complexities of divestment.

As UC regents met at the UC Merced encampment, Hernandez advised the pro-Palestinian protesters to engage directly with their local university administrators.

“You don’t do it under these types of conditions,” he told students as he sat in the sweltering heat under a shade canopy surrounded by Palestinian flags. “You go into a conference room and hash it out.”

But Hernandez also offered the activists some words of encouragement: “You are asking the right questions,” he said.

Huffman, the student activist, left the meeting feeling the regents probably counted on students not fully understanding the finer details of endowments. But the challenge, as she saw it, was ultimately not financial, but political.

“I do think it’s probably a complex process,” Huffman said. “But I guess the more will there is, the less complex it has to be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.