Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah says he won’t run for a 2nd term, likely ending long political career

Romney, 76, a former presidential candidate and governor of Massachusetts, said the country is ready for new leadership.

WASHINGTON — Utah’s Republican Sen. Mitt Romney said Wednesday that he will not run for reelection in 2024, creating a wide-open contest in a state that heavily favors Republicans.

Romney, a former GOP presidential nominee and governor of Massachusetts, made the announcement in a video, saying: “It’s time for a new generation of leaders. They’re the ones that need to make the decisions that will shape the world they will be living in.”

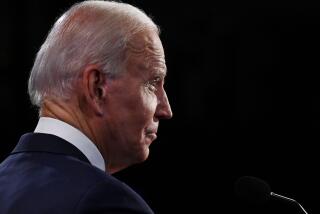

The senator, 76, noted that he’d be in his mid-80s at the end of another six-year Senate term. He didn’t mention the ages of President Biden, 80, or former President Trump, 77, the favorites for their parties’ 2024 presidential nominations, but said neither had done enough about the growing national debt, climate change and other long-term issues.

Romney is the sixth Senate incumbent to announce plans to retire in 2025, when their terms end, joining fellow Republican Mike Braun of Indiana and Democrats Thomas R. Carper of Delaware, Benjamin L. Cardin of Maryland, Dianne Feinstein of California and Debbie Stabenow of Michigan.

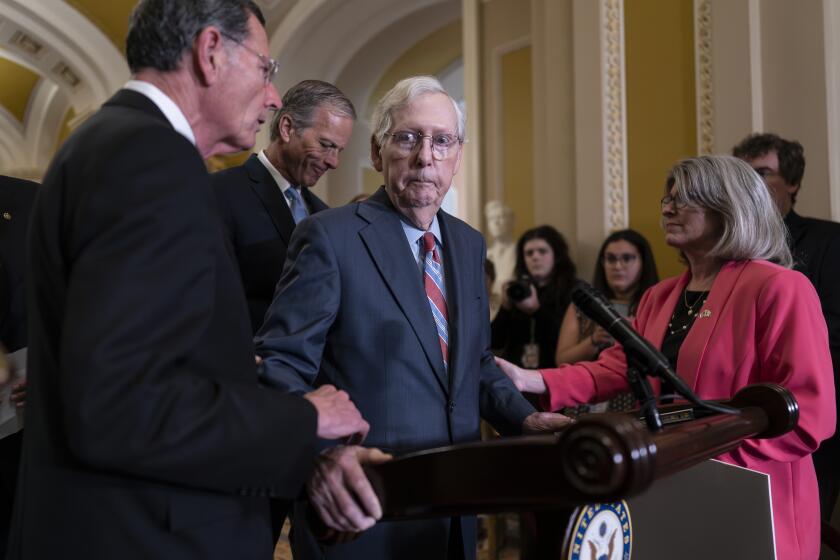

The Senate minority leader appeared confused at a news conference Wednesday. But America’s leadership is full of aging giants.

Romney easily won election in 2018 but was expected to face more resistance from his party as one of the most visible Republicans to break with Trump.

In 2020, Romney became the first senator in U.S. history to vote to convict a president from their own party in an impeachment trial, as the lone Republican to vote for conviction in Trump’s first impeachment. He was one of seven Republicans to vote to convict Trump in his second impeachment. Trump was acquitted both times.

A gathering of the Utah Republican Party’s most active members booed Romney months after his second impeachment vote, and a measure to censure him

narrowly failed. GOP candidates even flung the term “Mitt Romney Republican” at opponents in the 2022 midterm election campaign.

Still, Romney is seen as broadly popular in Utah, where the party has long favored civil conservatism and has resisted Trump’s brash and norm-busting style.

The state is home to the Lincoln Project, an anti-Trump PAC; Evan McMullin, an anti-Trump Republican who in 2016 made a long-shot presidential run; and GOP Gov. Spencer Cox, who has also criticized Trump.

A considerable majority of Utah residents belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The faith arrived with pioneers fleeing religious persecution, a legacy that has left the conservative church embracing immigrants and refugees.

Romney, an alum of Brigham Young University and one of the faith’s most visible members since his 2012 presidential campaign, built his reputation in Utah in part by turning around the scandal-plagued 2002 Winter Olympics, making the Games a showcase for Salt Lake City.

The wealthy former private equity executive was governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007. In 2006, he signed a state healthcare law with some of the same core features as President Obama’s 2010 federal healthcare law.

During his 2012 run for the White House, Romney struggled to shake the public perception that he was out of touch with regular Americans — especially after his comment, secretly recorded at a fundraiser, that he didn’t worry about winning the votes of “47% of Americans” who “believe they are victims” and “pay no income tax.”

After losing the election to Obama, Romney moved to Utah.

In 2016, he made his first major break with Trump ina scathing speech, denouncing the then-presidential hopeful as “a phony, a fraud” who wasn’t fit for the office.

After Trump won, Romney dined with him to discuss becoming his secretary of State.

During Romney’s primary race for his 2018 Senate run, he accepted Trump’s endorsement.

But he pledged in an op-ed that year that he’d “continue to speak out when the president says or does something which is divisive, racist, sexist, anti-immigrant, dishonest or destructive to democratic institutions.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.