Pop star Peso Pluma, who praises ‘El Chapo’ in his songs, is threatened with death by a rival drug cartel

MEXICO CITY — Mexican singer Peso Pluma has become one of the most popular musical acts on the planet in part by glorifying the world of drug trafficking.

He sings about diamond-encrusted pistols, smuggled shipments of cocaine and sending those who cross him “to the cemetery.”

In a music video for last year’s hit song “Siempre Pendientes,” or “Always Ready,” the gravelly-voiced artist wields a machine gun and tells the story of a foot soldier for Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán. It is one of several of the musician’s songs that praise the founder of the Sinaloa drug cartel.

Now the 24-year-old singer seems to have run afoul of a rival drug gang.

Four large banners appeared simultaneously in different parts of Tijuana on Tuesday warning Peso Pluma to cancel his planned concert in the city on Oct. 14.

The handwritten banners criticized the artist, whose real name is Hassan Emilio Kabande Laija, for his “disrespectful and loose tongue” and warned that if he doesn’t pull out of the show, it will be his last.

Peso Pluma is enjoying unprecedented success for a regional Mexican artist, topping the Billboard Hot 100 and Spotify’s Top 50. Just don’t ask him about that one song.

The threats were signed with the letters CJNG, the Spanish initials for the Jalisco New Generation cartel, which is Sinaloa’s main adversary in Tijuana and across much of the country.

The banners, which are being investigated by police, are a reminder of the risks that come with making the narcocorridos, or drug ballads, that Peso Pluma and many others sing.

And the controversy is adding fodder to a long-standing culture war over the appropriateness of music that exalts drug gangs in a country that has been so deeply ravaged by organized crime.

It’s not just drugs. Mexico’s cartels are fighting over avocados.

Corridos, which date back to 19th century rural Mexico, are one of the country’s oldest musical traditions. Originally known for recounting heroic tales of bandits and outlaws, they eventually began mythologizing the drug traffickers who were rapidly gaining influence across the country. Sometimes gangsters paid singers to memorialize them with a song.

Musicians dedicated to the genre have long faced backlash from the government, which since the 1980s has been trying, in various ways, to ban the music.

But the most serious threats have come from organized crime itself.

Dozens of narcocorrido stars have been killed here, sometimes by rivals of the hit men and drug dealers they’ve glorified in their songs.

The new threats against Peso Pluma are sparking headlines because he is one of Mexico’s most beloved young stars.

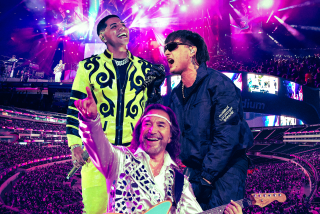

Boosted by his legions of fans on TikTok, Peso Pluma has skyrocketed to global fame, this year becoming one of the most listened-to artists on Spotify, where he boasts more than 50 million listeners a month. The singer has played at Coachella and on the “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and this week became the first regional Mexican musician to perform at the MTV Video Music Awards.

While narcocorrido culture was once largely contained to northern Mexico and immigrant communities in the United States, the lanky singer from Guadalajara — whose stage name translates to “Featherweight” — is at the vanguard of a new generation of musicians reinventing the genre and pushing it to fresh heights.

On Sunday night, the singer closed out a major music festival in Mexico City dedicated to “corridos tumbados,” as the newer generation of narcocorridos are known.

Wearing thick gold chains, with his signature mullet tucked behind a black baseball cap, the singer ran through his hits. Some of them are love songs, others odes to the narco underworld.

Rancho Humilde Records, headquartered in Downey, has become a trailblazer in Latin music by giving traditional Mexican corridos a hip-hop makeover.

As he crooned the lyrics of “El Gavilán,” or “The Hawk,” another song about a trafficker loyal to Guzmán, tens of thousands of audience members sang along.

Many speculate that it is that performance that may have triggered the Tijuana threats.

Peso Pluma has not addressed the incident.

Carlos Acevedo, a spokeman for the Baja California prosecutor’s office, said police had detained one person in connection to the threats, a man whom police observed manipulating one of the banners.

Tijuana Mayor Montserrat Caballero Ramírez said the city would determine in the coming days whether to cancel the concert, which she worried could put attendees at risk.

“We know that singers like ... Peso Pluma advocate for crime,” she told a group of reporters. “Unfortunately those who suffer the consequences are the citizens.”

Earlier this year, a narcocorrido band from Sinaloa state called Grupo Arriesgado was at a Tijuana mall signing autographs ahead of a planned concert when gunmen fired shots near the crowd. A banner signed by the Jalisco cartel and left at the scene warned the band to leave the city or suffer the consequences. The group canceled its show.

Caballero said she does not support an outright ban on the performance of narcocorridos, which other cities, including Cancun, have recently enacted.

“Parents are responsible for what our children listen to,” she said.

But she urged fans of the genre to interrogate their tastes. “Why they are seeing themselves projected in those songs?”

Peso Pluma has often deflected questions about the violent content of his music. Earlier this year, he hung up on a Times reporter who asked him about it during an interview.

But he seems to view himself as part of a long lineage of musicians — from rap to reggaeton — who have reflected lived reality, no matter how complicated or controversial.

“Corridos have always been very attacked and very demonized,” he told the Associated Press after performing at Coachella in April. “At the end of the day, it’s music.”

Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in the Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.