Ukraine passes Syria in deaths from cluster bombs, a weapon the world has tried to ban

AIN SHEEB, Syria — More than 300 people were killed and 600 wounded by cluster munitions in Ukraine in 2022, according to an international watchdog, pushing the war-torn nation past Syria as the country with the highest number of casualties from the controversial weapons.

The bombs open in the air and release scores of smaller bomblets, or submunitions. Russia’s widespread use of them in its invasion of Ukraine — and, to a lesser extent, their use by Ukrainian forces — helped make 2022 the deadliest year on record globally, according to the annual report released Tuesday by the Cluster Munition Coalition, a network of nongovernmental organizations advocating for a ban of the weapons.

The deadliest attack in Ukraine, according to the the country’s prosecutor general’s office, was a bombing on a railway station in the town of Kramatorsk that killed 53 people and wounded 135.

Meanwhile, in Syria and other war-battered countries in the Middle East, although active fighting has cooled down, the explosive remnants continue to kill and maim dozens of people every year.

The long-term danger posed to civilians by explosive ordnance peppered across the landscape for years — or even decades — after fighting has ceased has come under a renewed spotlight since the U.S. announced in July that it would provide Ukraine with them to use against Russia.

In Syria, 15 people were killed and 75 wounded by cluster munition attacks or their remnants in 2022, according to the coalition’s data. Iraq, where there were no new cluster bomb attacks reported last year, saw 15 people killed and 25 wounded. In Yemen, which also had no new reported attacks, five people were killed and 90 were wounded by the leftover explosives.

In his first comments on the delivery of cluster munitions to Ukraine from the U.S., Putin claimed that Russia has not used cluster bombs in its war.

The majority of victims globally are children. Because some types of these bomblets resemble metal balls, children often pick them up and play with them without knowing what they are.

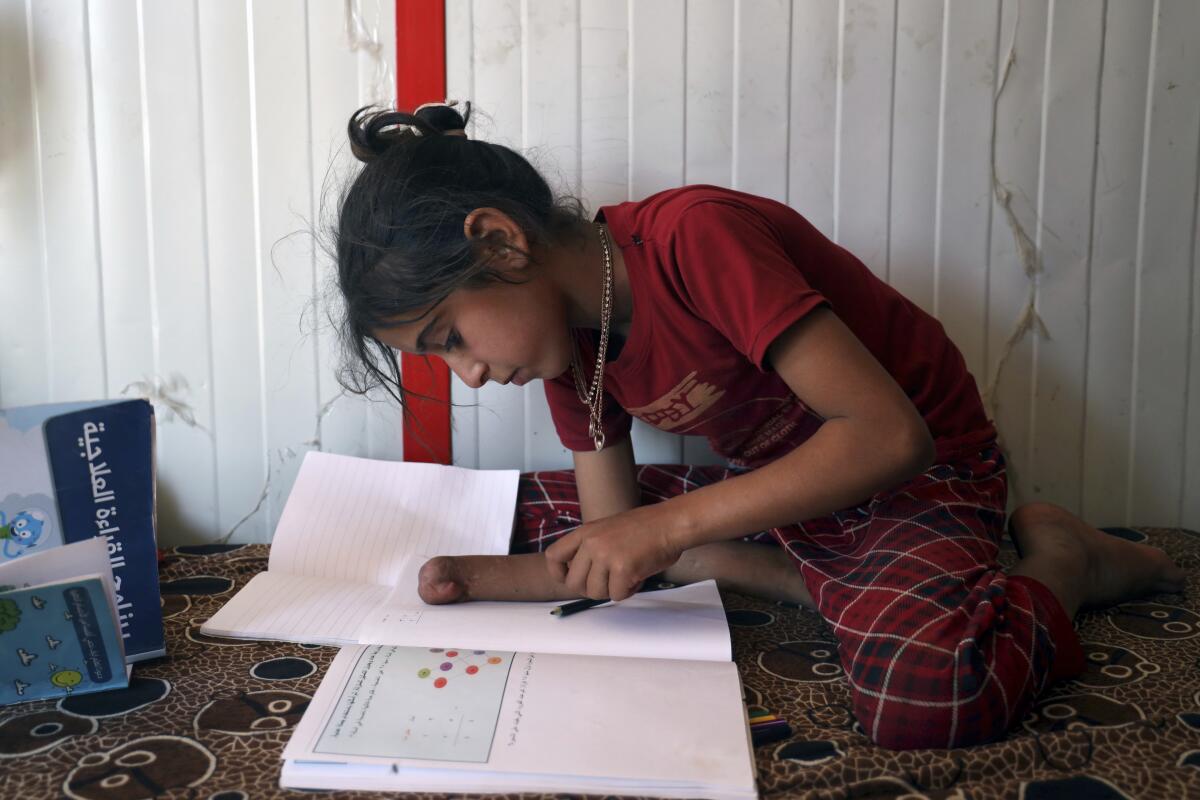

Among the casualties are 12-year-old Rawaa Hassan and her 10-year-old sister, Doaa, whose family has lived at a camp near the village of Ain Sheeb in northern Syria’s opposition-held Idlib province since being displaced from their hometown six years earlier.

The area where they live in Idlib had frequently come under airstrikes, but the family had escaped from those unharmed.

During the holy Muslim month of Ramadan last year, as the girls were coming home from school, their mother, Wafaa, said, they picked up an unexploded bomblet, thinking it was a piece of scrap metal they could sell.

Biden is right about providing cluster bombs to help fight Russia’s invasion. The morality of weapons depends partly on the context in which they’re used.

Rawaa lost an eye, Doaa a hand. In a cruel coincidence, the girls’ father had died eight months earlier after he stepped on a cluster munition remnant while gathering firewood.

The girls “are in a bad state psychologically” since the two accidents, said their uncle Hatem Hassan, who now looks after them and their mother. They have difficulty concentrating, and Rawaa often flies off the handle, hitting other children at school.

“Of course we’re afraid, and now we don’t let them play outside at all anymore,” he said.

Some 124 countries have joined a United Nations convention banning cluster munitions. The U.S., Russia, Ukraine and Syria are among the holdouts.

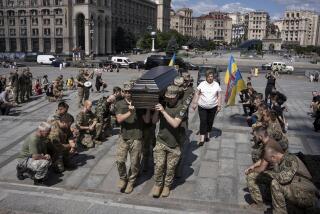

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky says Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov will be replaced this week by Rustem Umerov, a Crimean Tatar lawmaker.

Deaths and injuries from cluster munition remnants have continued for decades after wars ended in some cases — including in Laos, where people still die yearly from Vietnam War-era U.S. bombing that left millions of unexploded cluster bomb-lets.

Alex Hiniker, an independent expert with the Forum on the Arms Trade, said casualties had been dropping worldwide before the 2011 uprising-turned-civil war in Syria.

“Contamination was being cleared; stockpiles were being destroyed,” she said. But the progress “started reversing drastically” in 2012, when the Syrian government and allied Russian forces began using cluster bombs against the opposition in Syria.

The numbers had dropped off as the war in Syria turned into a stalemate, although at least one new cluster bomb attack was reported in Syria in November. But they quickly spiked again with the conflict in Ukraine.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

U.S. officials have defended the decision to provide cluster bombs to Ukraine as necessary to level the playing field in the face of a stronger opponent and have insisted that they will take measures to mitigate harm to civilians. This would include sending a version of the munition with a reduced “dud rate,” meaning fewer unexploded rounds left behind after the conflict.

Hiniker said she and others who track the effects of cluster munitions are “baffled by the fact that the U.S. is sending totally outdated weapons that the majority of the world has banned because they disproportionately kill civilians.”

The “most difficult and costly part” of dealing with the weapons, she said, “is cleaning up the mess afterwards.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.