Rescuers brave snipers and race time to save Ukrainians in Russian-occupied flood zones

KHERSON, Ukraine — At last, help came for Vitalii Shpalin. From a distance, he spotted the small Ukrainian rescue boat traversing floodwaters that had submerged the 60-year-old’s entire neighborhood after a catastrophic dam collapse in the country’s embattled south.

He and others boarded with sighs of relief — interrupted suddenly by the crackle of bullets.

Shpalin ducked, and a bullet scraped his back. He felt one pierce his arm, then his leg. The boat’s rescue worker cried into the radio for reinforcements. “Our boat is leaking,” Shpalin heard him say. An elderly man died before his eyes, his lips turning blue.

Their vessel, taking civilians to safety in Kherson city across the river, had been targeted by Russian soldiers positioned in a nearby house, according to Ukrainian officials and witnesses on the boat.

“They [Russians] let the boats through, those coming to rescue people,” Shpalin said. “But when the boats were full of people, they started shooting.”

Massive flooding from the destruction of the Kakhovka dam on June 6 has devastated towns along the lower Dnipro River in the Kherson region, a front line in the war. Russia and Ukraine accuse each other of causing the breach.

In the chaotic early days of flooding, Ukrainian rescue workers in private boats provided a lifeline to desperate civilians trapped in flooded areas of the Russian-occupied eastern bank — that is, if the rescue missions could brave the drones and Russian snipers.

Help has been slow in coming to Oleshky, a Russian-occupied town in Ukraine that was inundated after a catastrophic dam collapse this week.

The boats have carried volunteers and plainclothes servicemen, shuttling across from Ukrainian-held areas on the western bank to evacuate people stuck on rooftops, in attics and elsewhere.

Now, that window is closing. As floodwaters recede, rescuers are increasingly cut off by putrid mud. And more Russian soldiers are returning, reasserting control.

Accounts of Russian assistance vary among survivors, but many evacuees and residents accuse Russian authorities of doing little or nothing to help displaced residents. Some civilians said evacuees were sometimes forced to present Russian passports if they wanted to leave.

Russia’s Defense Ministry did not immediately respond to requests from the Associated Press for comment about actions by authorities in the Russian-occupied flood zone, or about the attack on the rescue boat.

Floodwaters from a collapsed dam kept rising in southern Ukraine, forcing hundreds of people to flee their homes in a major emergency operation.

The AP spoke with 10 families rescued from the eastern bank, as well as with rescue workers, officials and victims injured on the rescue missions.

“The Russian Federation provided nothing. No aid, no evacuation. They abandoned people alone to deal with the disaster,” said Yulia Valhe, evacuated from the Russian-occupied town of Oleshky. “I have my friends who stayed there, people I know who need help. At the moment I can’t do anything except to say to them, ‘Hold on.’”

At least 150 people have been rescued by Ukraine from Russian-controlled areas in the risky evacuation operations, said government spokesperson Oleksandr Tolokonnikov. Nearly 2,750 people have been rescued from flooded regions controlled by Ukraine.

Russian forces shelled a southern Ukrainian city that was inundated in a catastrophic dam collapse, forcing the suspension of some rescue work.

A local organization, Helping to Leave, which assists Ukrainians living under Russian occupation to escape, said it received requests from 3,000 people in the occupied zone.

“We will surely do everything we can, but we also cannot expose our people to danger,” said Tolokonnikov.

“Russians keep threatening us and fulfilling their threats by shooting people in the back,” he said.

Olha, another resident of Oleshky, said she had heard about the rescue missions but didn’t know how to get on a list. “If we could, we would have done the same, but I didn’t know how,” she said, declining to give her last name for safety reasons.

Rescuers have often used information provided by relatives of those stranded. Military drone pilots have searched for people and plotted routes through the fast-moving waters laden with debris, while navigating around Russian troop positions.

They also have delivered water, food and cigarettes to people with a note “from Santa.”

Valerii Lobitskyi, a volunteer rescuer, said shelling often derailed the missions. He has been shot at once, and on another occasion had to abort a mission to rescue an elderly woman after a close call with a Russian motorboat.

Every civilian evacuated from the eastern bank carried a harrowing tale of survival, of racing to relocate to higher ground. They described the initial scramble on the morning of June 6. Within hours, the water came gushing, reaching their ankles and then submerging entire floors.

In Oleshky, many residents moved from the outskirts of town to the center, which sits on an elevated plain.

Valhe, who was rescued with her family on Monday, said neighbors and friends tried to save people themselves in the absence of an official rescue effort.

“I saw soldiers, I saw FSB workers [Russia’s Federal Security Service], but no rescue service,” she said.

One elderly man tried to flee the deluge by climbing a tree. But the winds were too strong. Valhe heard his cries for help, but knew that if she tried to approach him she would perish in the current.

He told her, “My dear, stay put, don’t follow me.”

She watched him drown.

Shpalin said he lied to Russian soldiers when they tried to evacuate him to another area. He had heard from others who accepted the Russian offer that they were taken only to a nearby village and told they could not go farther unless they agreed to obtain Russian passports.

The destruction of the Kakhovka dam in southern Ukraine is swiftly evolving into a long-term environmental catastrophe.

Shpalin told the soldiers he would not leave because he had lost his documents in the flood. In reality, they were on his person. “I didn’t believe them,” he said.

When the Ukrainian rescuers found him, he was sheltering with other civilians on a hill in the village of Kardashynka.

The attack that wounded Shpalin on the evacuation boat on June 11 killed three civilians and injured 10. At least two police officers also were wounded. Kherson authorities and President Volodymyr Zelensky’s chief of staff said Russian soldiers fired the shots.

Drone footage obtained by the AP shows gunshots being fired from a nearby summer home as the evacuation boat passes an estuary. The video’s authenticity was confirmed by Tolokonnikov.

Serhii, 59, another evacuee on the boat, said he saw Russian soldiers on the balcony of the house. They shouted something — “Move on,” or “Don’t move” — then fired, he said. Serhii, who would give only his first name because his family still lives in occupied territory, threw his body over his wife’s to protect her.

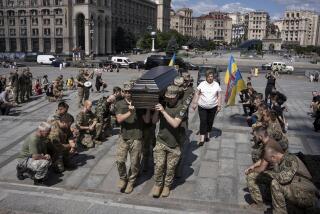

Some days later, in Kherson, the boom of artillery resounded in the background as 46-year-old Vitalii Holodniak, one of those killed in the boat attack, was laid to rest.

His sister Svitlana Nosik, 56, held up his death certificate. “Place of death: Dnipro River, evacuation boat,” it read.

“That is not how I expected to greet my brother in Kherson,” she said.

Another evacuee, Kateryna Krupych, said she looked out the window on June 7 to find mucky water surrounding her home on the island of Chaika, in the gray zone between front lines. Houses floated by. She packed up her family’s supplies and they left in a boat, but got separated along the way. Eventually, they were all rescued by Ukrainians.

Krupych said the previous eight months under Russian occupation had been hard. Her family survived by relying on the kindness of neighbors who fled to Kherson city. They told her where to find the spare keys to their homes and leftover food supplies.

“It was mentally difficult when the [Russians] entered our island, when they terrorized us,” she said. Russian soldiers frequently passed their home, she said, pressuring them to leave.

For Olha, still in Oleshky, the costs of the dam collapse continue to be revealed. Many houses are collapsing, she said, and she struggles to find drinking water and food. There is the risk of water-borne diseases.

Plus, “[Russians] can force-evacuate people — we are scared of this, we don’t want to go to their territories,” she said. “We don’t want to be forgotten.”

Kullab reported from Kyiv. Maloletka and McNeil reported from Kherson.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.