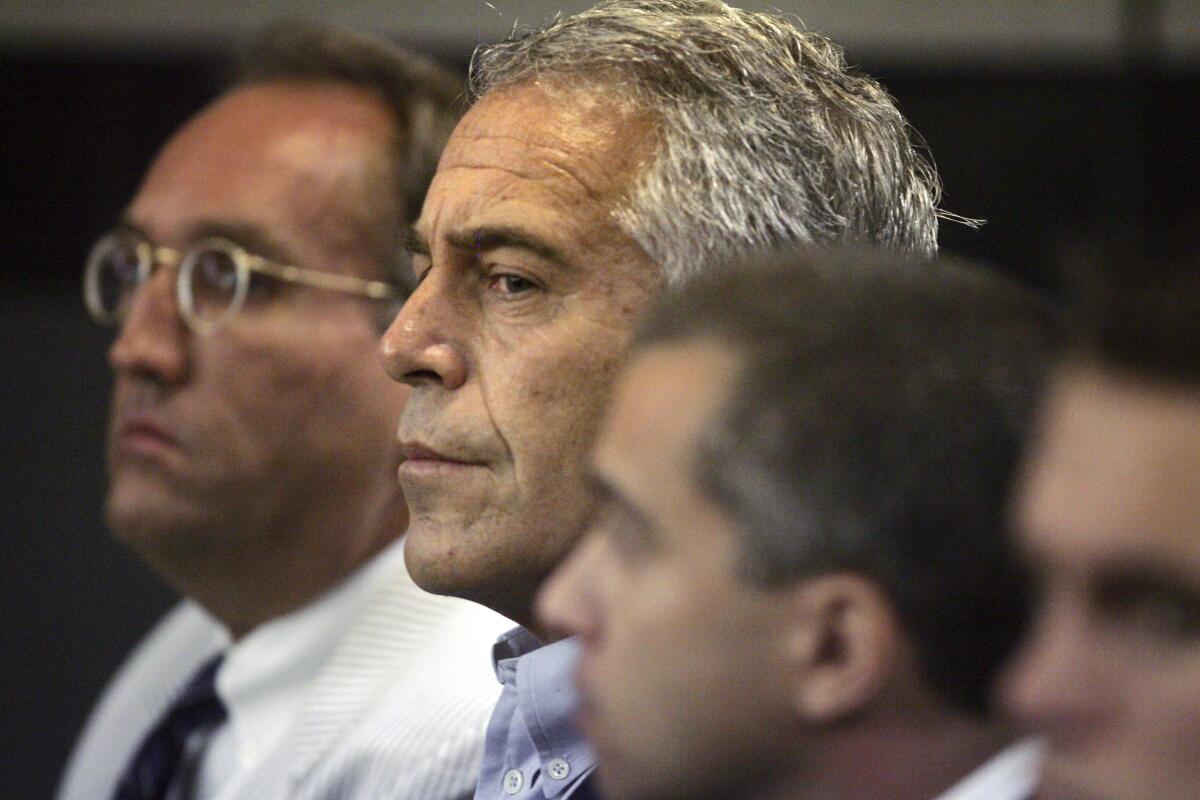

Documents reveal new details of Jeffrey Epstein’s death and its frantic aftermath

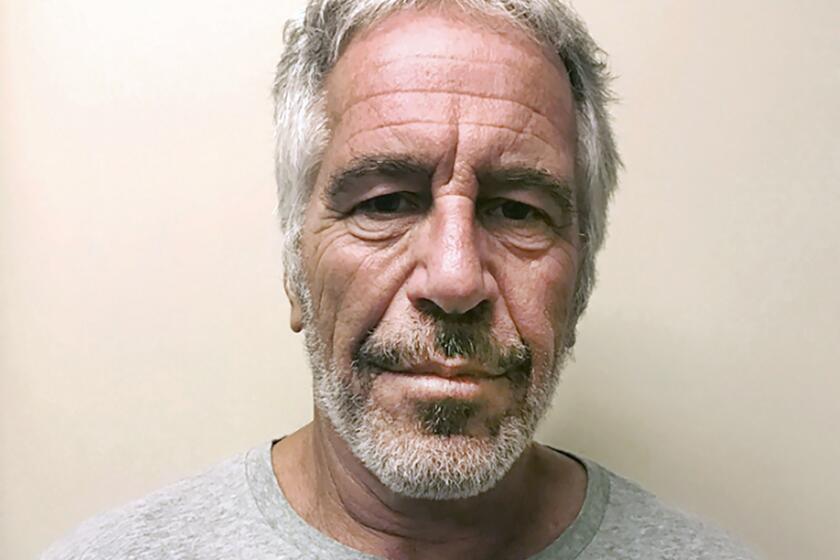

NEW YORK — Two weeks before ending his life, Jeffrey Epstein sat in the corner of his Manhattan jail cell with his hands over his ears, desperate to muffle the sound of a toilet that wouldn’t stop running.

Epstein was agitated and unable to sleep, jail officials observed in records newly obtained by the Associated Press. He called himself a “coward” and complained that he was struggling to adapt to life behind bars following his July 2019 arrest on federal sex-trafficking and conspiracy charges — his life of luxury reduced to a concrete and steel cage.

The disgraced financier was under psychological observation at the time for a suicide attempt days earlier that left his neck bruised and scraped. After a 31-hour stint on suicide watch, Epstein insisted he wasn’t suicidal, telling a jail psychologist that he had a “wonderful life” and “would be crazy” to end it.

On Aug. 10, 2019, Epstein was dead.

Nearly four years later, the AP has obtained more than 4,000 pages of documents related to Epstein’s death from the federal Bureau of Prisons under the Freedom of Information Act. They include a detailed psychological reconstruction of the events leading to Epstein’s suicide, as well as his health history, internal agency reports, emails, memos and other records.

Taken together, the documents obtained Thursday provide the most complete account to date of Epstein’s detention and death, and the chaotic aftermath. The records help to dispel the many conspiracy theories surrounding Epstein’s suicide underscoring how fundamental failings at the Bureau of Prisons — including severe staffing shortages and employees cutting corners — contributed to Epstein’s death.

Prosecutors said that Ghislaine Maxwell deserved 30 to 55 years in prison for helping financier Jeffrey Epstein sexually abuse underage girls.

They shed new light on the federal prison agency’s muddled response after Epstein was found unresponsive in his cell at the now-shuttered Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York City.

In one email, a prosecutor involved in Epstein’s criminal case complained about a lack of information from the Bureau of Prisons in the critical hours after his death, writing that it was “frankly unbelievable” that the agency was issuing news releases “before telling us basic information so that we can relay it to his attorneys who can relay it to his family.”

In another email, a high-ranking Bureau of Prisons official suggested to the agency’s director that reporters must have been paying jail employees for information about Epstein’s death because they were reporting details of the agency’s failings — a spurious accusation that impugned the ethics of journalists and the agency’s own workers.

The documents also provide a fresh window into Epstein’s behavior during his 36 days in jail, including his previously unreported attempt to connect by mail with another high-profile pedophile: Larry Nassar, the U.S. gymnastics team doctor convicted of sexually abusing scores of athletes.

Deutsche Bank will pay $75 million to settle a lawsuit contending that it should have seen evidence of sex-trafficking by then-client Jeffrey Epstein.

Epstein’s letter to Nassar was found “returned to sender” in the jail’s mail room weeks after Epstein’s death.

“It appeared he mailed it out and it was returned back to him,” the investigator who found the letter told a prison official by email. “I am not sure if I should open it or should we hand it over to anyone?”

The letter itself was not included among the documents turned over to the AP.

The night before Epstein’s death, he excused himself from a meeting with his lawyers to make a phone call to his family. According to a memo from a unit manager, Epstein told a jail employee that he was calling his mother, who had been dead for 15 years at that point.

Epstein’s death put increased scrutiny on the Bureau of Prisons and led the agency to close the Metropolitan Correctional Center in 2021. It spurred an AP investigation that has uncovered deep, previously unreported problems within the agency, the Justice Department’s largest, with more than 30,000 employees, 158,000 inmates and an $8-billion annual budget.

The U.S. Virgin Islands has reached a settlement of more than $105 million in a sex trafficking case against the estate of financier Jeffrey Epstein.

An internal memo, undated but sent after Epstein’s death, attributed problems at the jail to “seriously reduced staffing levels, improper or lack of training, and follow up and oversight.” The memo also detailed steps the Bureau of Prisons has taken to remedy lapses Epstein’s suicide exposed, including requiring supervisors to review surveillance video to ensure that officers made required cell checks.

Epstein’s lawyer, Martin Weinberg, said people detained at the facility endured “medieval conditions of confinement that no American defendant should have been subjected to.”

“It’s sad, it’s tragic, that it took this kind of event to finally cause the Bureau of Prisons to close this regrettable institution,” Weinberg said in a phone interview.

The workers tasked with guarding Epstein the night he killed himself, Tova Noel and Michael Thomas, were charged with lying on prison records to make it seem as though they had made their required checks before Epstein was found lifeless. Epstein’s cellmate did not return after a court hearing the day before, and prison officials failed to pair another prisoner with him, leaving him alone.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Prosecutors alleged that Noel and Thomas sat at their desks just 15 feet from Epstein’s cell, shopped online for furniture and motorcycles, and walked around the unit’s common area instead of making required rounds every 30 minutes.

During one two-hour period, both appeared to have been asleep, according to their indictment. Noel and Thomas admitted to falsifying the log entries but avoided prison time under a deal with federal prosecutors. Copies of some of those logs were included among the documents released Thursday, with the guards’ signatures redacted.

Another investigation, by the Justice Department’s inspector general, is ongoing.

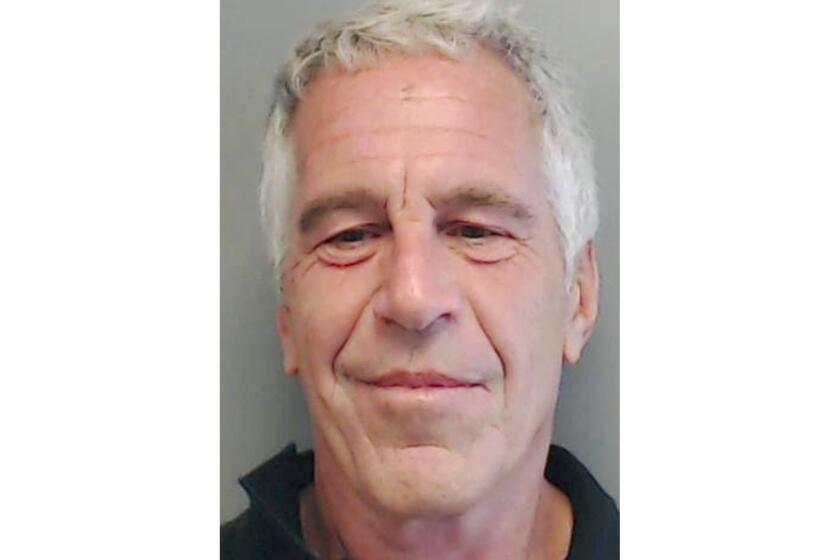

Epstein arrived at the Metropolitan Correctional Center on July 6, 2019. He spent 22 hours in the jail’s general population before officials moved him to the special housing unit “due to the significant increase in media coverage and awareness of his notoriety among the inmate population,” according to the psychological reconstruction of his death.

A fund to provide money to victims of financier Jeffrey Epstein is winding down after announcing payments of nearly $125 million to over 135 people.

Epstein later said he was upset about having to wear an orange jumpsuit provided to inmates in the special housing unit and complained about being treated like he was a “bad guy” despite being well-behaved behind bars. He requested a brown uniform for his near-daily visits with his lawyers.

During an initial health screening, the 66-year-old said that he had more than 10 female sexual partners within the previous five years. Medical records showed he was suffering from sleep apnea, constipation, hypertension, lower back pain and pre-diabetes and had been previously treated for chlamydia.

Epstein did make some attempts to adapt to his jailhouse surroundings, the records show. He signed up for a kosher meal and told prison officials, through his lawyer, that he wanted permission to exercise outside. Two days before he was found dead, Epstein bought $73.85 worth of items from the prison commissary, including an AM/FM radio and headphones. He had $566 left in his account when he died.

Epstein’s outlook worsened when a judge denied him bail July 18, 2019 — raising the prospect that he’d remain locked up until trial. If convicted, he faced up to 45 years in prison. Four days later, Epstein was found on the floor of his cell with a strip of bedsheet around his neck.

The billionaire co-founder of Microsoft Corp. said he and the late sex offender had a series of meetings to discuss a philanthropy project.

Epstein survived that suicide attempt. His injuries didn’t require going to the hospital. He was placed on suicide watch and, later, psychiatric observation. Jail officers noted in logs that they observed him “sitting at the edge of the bed, lost in thought,” and sitting “with his head against the wall.”

Epstein expressed frustration with the noise of the jail and his lack of sleep. During his first few weeks at the Metropolitan Correctional Center, Epstein didn’t have the sleep apnea breathing apparatus that he used. Then, the toilet in his cell started acting up.

“He was still left in the same cell with a broken toilet,” the jail’s chief psychologist wrote in an email the next day. “Please move him to the cell next door when he returns from legal as the toilet still does not work.”

The day before Epstein ended his life, a federal judge unsealed about 2,000 pages of documents in a sexual abuse lawsuit against him. That development, prison officials observed, further eroded Epstein’s previous elevated status.

That fall from grace, a lack of significant interpersonal connections and “the idea of potentially spending his life in prison were likely factors contributing to Mr. Epstein’s suicide,” officials wrote.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.