With an Erdogan win, Turkey would continue to play both sides of the U.S.-Russia divide

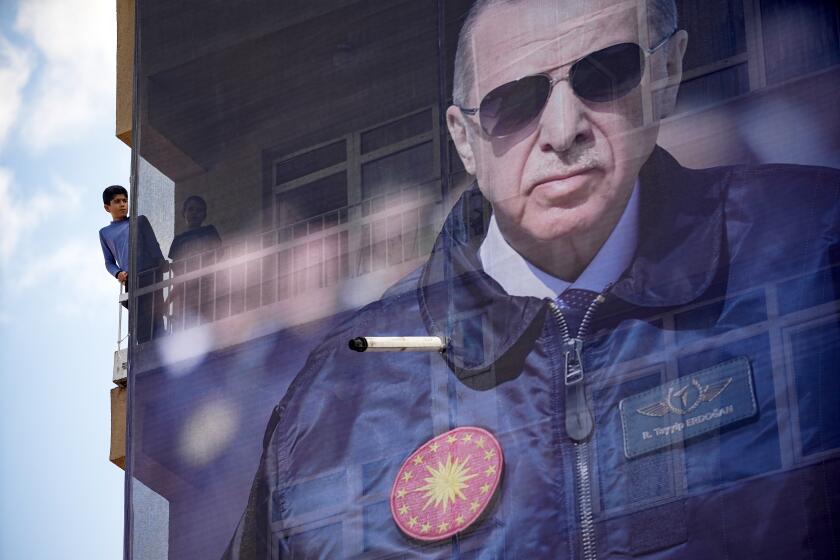

ISTANBUL — For the last several years, Turkey under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has played both sides of the global geopolitical divide: It belongs to the Western NATO alliance but has also nurtured ever-closer ties with Russia.

A NATO stalwart for more than seven decades, Turkey served inside the alliance’s peacekeeping missions in various war zones, but then more recently purchased military equipment from Russia and refused entry to new NATO members that might offend Moscow.

Turkey’s unique and seemingly contradictory position has become amplified since Russia invaded neighboring, pro-West Ukraine 15 months ago, with Erdogan again leveraging himself as a valuable ally to both the U.S. and Europe on one side and to Russia on the other. He has often seemed to land with Russia over his Western partners.

The question now is how much — or whether — Turkey’s place on the world stage will change following Sunday’s presidential runoff election, in which Erdogan is widely expected to prevail but only after conquering unprecedented opposition.

“He will continue to play an important — but uncomfortable — role from the Western perspective,” said Emre Peker, Europe director for the Eurasia Group, a risk-analysis organization.

The election battle between Turkey’s president and his main challenger is increasingly focused on one issue: Syrian refugees in their country.

Joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization less than three years after it was founded in the ashes of World War II, Turkey was until recently the only Muslim country in the alliance. With a population of 85 million and a massive land area that literally straddles East and West, it has the alliance’s second-largest army.

Before Erdogan became president in

2014, Turkey was staunchly secular, so much so that the wearing of headscarves by women was banned in many official venues.

But Erdogan has steadily pushed the nation into a more religious sphere, while seizing more autocratic powers. Those shifts have taken him and the country slightly out of step with NATO and, in the view of the president and his closest advisors, freer to strike deals and allegiances with dire enemies of the U.S. and NATO, including Russia.

Privately, some Biden administration officials say they would relish the election of someone other than Erdogan, who has not been invited to the White House since President Biden took office. During a visit Erdogan made to Washington during the Trump presidency, his guards beat up peaceful protesters and quickly left the country to avoid criminal prosecution.

Sen. Robert Menendez, the New Jersey Democrat who chairs the body’s Foreign Relations Committee, has long been critical of Erdogan and his overtures to Moscow.

“Will [Turkey] after the election be the NATO ally we always wanted it to be, or will it be in turmoil?” he said in a speech last week in New York.

No doubt, one person who would be happy to see Erdogan reelected is Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since Putin launched the invasion of Ukraine and spurred a firestorm of sanctions on his country’s economy, Turkey has become a primary lifeline for Moscow, with the pugnacious Erdogan insisting on maintaining economic and diplomatic links.

“We are not at a point where we would impose sanctions on Russia like the West have done,” Erdogan said in an interview with CNN last week. “We are not bound by the West’s sanctions.

“We are a strong state and we have a positive relationship with Russia,” he said. “Russia and Turkey need each other in every field possible.”

As anticipation builds for a counteroffensive, Ukrainian forces are desperate to lay their hands on Western tanks that could help turn the war’s tide.

At the same time, Erdogan portrays himself as valuable to the West. He claims he could be key in negotiating peace, and he helped bring Putin on line in last year’s Black Sea Grain Initiative, a deal brokered by the United Nations that allowed grain exports from Ukraine to continue and ameliorated a surge in food prices. He also helped negotiate a prisoner exchange between Ukraine and Russia.

In some ways, Erdogan and Putin make an odd pair. They supported opposing sides in the civil wars in Syria and Libya as well as in the ongoing conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Relations reached a nadir in 2015 when Turkey shot down a Russian warplane near the Syrian-Turkish border.

But rather than driving a wedge between the two leaders, the war in Ukraine has only deepened their relationship.

Russia is the largest supplier of energy to Turkey, providing a third of its oil and gas imports. Earlier this month, Moscow agreed to delay some of Turkey’s natural gas payments — a move seen as a favor to Erdogan ahead of the election. The two countries are also working together on Turkey’s first nuclear power plant, which is set to open later this year.

The closure of the Nord Stream pipeline, which would have conveyed oil from Russia to Germany and Western Europe, has also prompted Russia to push for Turkey to become a regional gas hub for trade with the European Union.

Bilateral trade, meanwhile, topped $62 billion last year, and Turkey remains the top choice for Russian tourists — more than 5.2 million visited last year. And with Europe all but sealed to Russian citizens, Turkey has become a prime destination for Russian expats to live and work — a development one can see every day on the streets of Moda, a trendy neighborhood on Istanbul’s Asian side, where Russian couples with baby strollers are a frequent sight and cafes are filled with Russian men and women hunched intently over their laptops.

“For the last year? All our clients have been Russians,” said Dehlan Agirman, a longtime real estate agent there. The influx, she said, had spurred a doubling of rental prices in the district.

“Normally I would have three deals a month or something,” she said. “Now it’s more than seven. Most are young couples, with remote work. And they’re willing to pay three or six months in advance.”

The war in Ukraine has jacked the global arms trade, fueling a new appetite for materiel not just in Moscow and Kyiv but also around the world.

Turkey has provided drones and other materiel to Ukraine, but the country under Erdogan shares much of Putin’s dislike of the West, and that has made him a prickly partner in NATO.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, both Sweden and Finland — which have long staked out an official position of neutrality — sought membership in the transatlantic alliance. The decision to admit new members must be unanimous, and both cases came down to Turkey, which eventually conceded to Finland but not to Sweden.

Erdogan claims that Sweden harbors Kurdish activists tied to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a group both Turkey and the United States consider a terrorist organization.

The U.S. Congress punished Turkey for blocking Sweden by preventing it from buying American-made F-16 warplanes. Turkey’s purchase of a Russian S-400 missile defense system around 2021 had already cost it access to F-35s because of concerns that Russia could rig the system to spy on the West.

Erdogan’s opponent in Sunday’s runoff, 74-year-old Kemal Kilicdaroglu, has said he would improve Turkey’s relationship with the West and move to restart a long-stalled bid to join the European Union. He has also lambasted Erdogan for being too close with Putin.

But most analysts predict that Erdogan will triumph. In the initial electoral round two weeks ago, he garnered 49.5% of the 50% needed to win outright. Kilicdaroglu took 44.9%, but the third-place finisher, who won 5.2%, has since endorsed Erdogan.

Whoever wins will face the instability of a flagging economy and the aftermath of February’s cataclysmic earthquakes that ravaged the country’s south, killing at least 50,000 people and leaving millions homeless.

Erdogan’s populist maneuverings ahead of the election, including raising the minimum wage and pensions and offering free gas to citizens, are expected to add further pressure on state coffers, even as the Turkish lira remains at a historic low.

Excavators dig out 200-foot trenches in southern Turkey to bury the bodies of earthquake victims. The death toll rises to more than 20,000.

One school of thought is that the need for Western aid will push him into more moderate positions seen more favorably by the U.S. and Europe.

But Gonul Tol, founding director of the Turkey program at the Middle East Institute, a Washington think tank, takes a different view.

“I don’t see how Western money is going to all of a sudden start pouring into Turkey, in a country where Erdogan is probably going to double down on repression at home,” she said, referring to the president’s crackdown on thousands of dissidents and other perceived opponents.

That could prompt him to reach out more eagerly to Russia, Qatar or Saudi Arabia to finance any budgetary shortfalls.

“Usually, when autocrats face more instability at home, they tend to pursue a more unpredictable anti-Western nationalist foreign policy,” Tol said.

Times staff writers Bulos reported from Istanbul and Wilkinson from Washington.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.