Sons of Mexico’s El Chapo: We don’t make fentanyl — or feed victims to tigers

MEXICO CITY — We don’t feed our adversaries to tigers, nor do we beat them to death with baseball bats.

We didn’t vow to “flood the streets” of the United States with fentanyl.

“We are victims of persecution and have been made into scapegoats.”

Those are among the assertions in a startling letter to the media from “Los Chapitos,” sons of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán — the notorious ex-kingpin of the Sinaloa cartel now serving a life sentence in a U.S. “supermax” prison in Colorado. In 2019, El Chapo was convicted in federal court in Brooklyn, N.Y., of smuggling hundreds of tons of cocaine and other drugs, conspiring to murder rivals and heading one of the world’s largest trafficking networks.

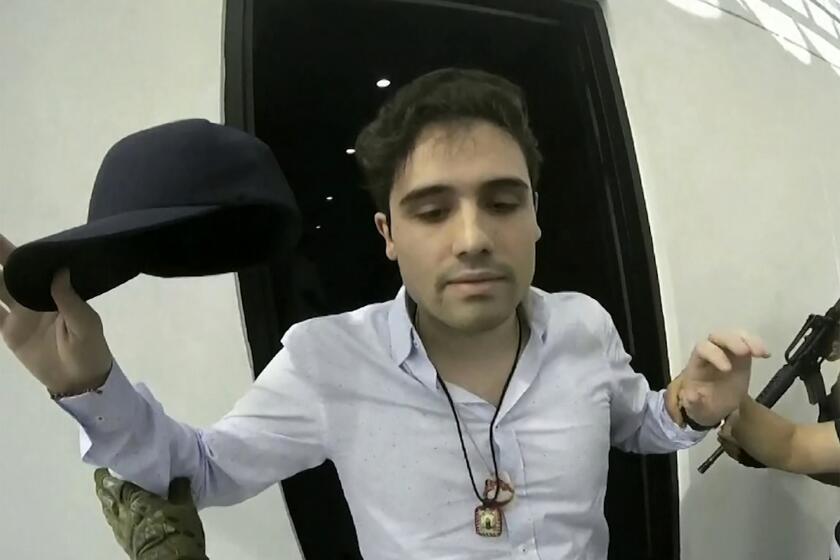

In a series of federal indictments unsealed last month in New York, four of his sons were charged with drug trafficking and other crimes, and accused of leading a cartel faction that constitutes “the largest, most violent and most prolific fentanyl trafficking operation in the world.” The Justice Department has offered multimillion-dollar rewards for information leading to the capture of Jesús Alfredo, 36, Iván Archivaldo, 39, and Joaquín, also 36 — who are fugitives.

The other brother, Ovidio Guzmán López, 33, alias “The Mouse,” was arrested outside Culiacan, in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, in January. Mexican authorities conducting the arrest faced attacks from cartel gunmen that left at least 29 dead, including 10 soldiers. The attacks shut down roads and airports and shut down Culiacan. U.S authorities are seeking Ovidio Guzmán’s extradition from Mexico.

In Mexico stronghold of Sinaloa cartel, armed men burn vehicles, storm airport to try to prevent capture of drug lord Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s son.

In the various federal indictments, the brothers stand accused of pioneering the manufacture, cross-border smuggling and U.S. distribution of fentanyl. The synthetic opioid is blamed for thousands of deaths in the United States annually.

Clearly keen to avoid their father’s fate, the sons sent their four-page missive to Mexico’s Milenio news outlet, which published it late Wednesday. A lawyer for the family, José Refugio Rodríguez, confirmed to reporters that “los muchachos” — the brothers — wrote the unsigned letter, although it was unclear which, or how many of El Chapo’s 10 or more sons were responsible for it.

The unusual missive made headlines here as tensions between Washington and Mexico City have been rising over fentanyl. Some Republican lawmakers have even suggested deploying U.S. troops to Mexico to help stem the menace.

For Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, appearing to stand up to the United States has proved to have political benefits at home.

That has raised the ire of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has insisted that his country is only a transit corridor for fentanyl, not a manufacturing hub.

U.S. officials counter that the vast majority of illegal fentanyl in the United States is produced clandestinely in Mexico from precursor chemicals imported from China. The drug is then smuggled across the border to thriving U.S. markets from Los Angeles to New York, they say.

Among other things, the letter from Los Chapitos seeks to refute allegations in a recent series of U.S. indictments naming Sinaloa cartel operatives across the world, including associates in China.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration said it had infiltrated the infamous cartel and uncovered lurid details — including the torture of captured rivals, experiments with fentanyl on human guinea pigs (some of whom allegedly died), and the feeding of enemies “dead or alive” to pet tigers, according to one indictment.

“We don’t have and didn’t have tigers,” the brothers declared in their letter.

The siblings also denied another allegation — that they planned to flood the United States to create “streets of junkies,” according to U.S. officials.

Instead, the brothers repudiated the notion that they had ever engaged in fentanyl production or smuggling.

The Justice Department has charged 28 members of Mexico’s powerful Sinaloa cartel, including sons of notorious drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman.

The brothers portray themselves as innocents who have been victimized because of their father’s global notoriety. In rambling passages, they denounce others who profit from their father’s name in producing merchandise including clothing, alcoholic drinks and so-called narco-corridos, ballads that lionize the exploits of El Chapo.

“The benefits are incalculable for people and businesses who today use our name,” the brothers wrote, noting the role of social media in disseminating the El Chapo brand. “We wanted to choose a distinct life with good studies, which was denied to us.”

Before their father’s arrest, Los Chapitos were often portrayed the Mexican media as slothful, hard-drinking playboys who drove luxurious cars and spent their days partying at fancy restaurants and resorts — living off the proceeds of the ill-gotten gains of their father, who had risen from humble origins to become, according to U.S authorities, the world’s richest drug smuggler.

Calling themselves “prudent,” the brothers contend that other groups traffic in fentanyl, sometimes using their name as cover. The siblings also assert that “no judge or magistrate will treat us with justice.”

There was no immediate reaction to the letter from the Drug Enforcement Administration or the Justice Department.

The letter probably was an effort to drum up some public sympathy south of the border as U.S. authorities increasingly press their Mexican counterparts to take down the three fugitive brothers.

El Chapo is in prison, but Sinaloa cartel remains strong. “This is a city filled with drug lords,” a Mexican journalist said. “We have 20 ‘El Chapos’ here.”

“I firmly believe that Los Chapitos are feeling the pressure,” said Mike Vigil, former head of international operations for DEA. “And they are probably trying to gain some public support from politicians who may want to extradite them.”

Mexican President López Obrador declined to comment on the contents of the letter, but vowed that there was no “protected group” in Mexico.

In February, Mexico’s former top security chief, Genaro García Luna, was convicted in federal court in New York of taking bribes to protect the Sinaloa cartel and other gangs whom he was tasked with combating. García Luna, who could face up to life in prison when sentenced, served as Mexico’s top security official from 2006 to 2012 under the administration of ex-President Felipe Calderón.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.