Anger, tears, a birthday serenade. What happened after a deadly fire in Mexico migrant lockup

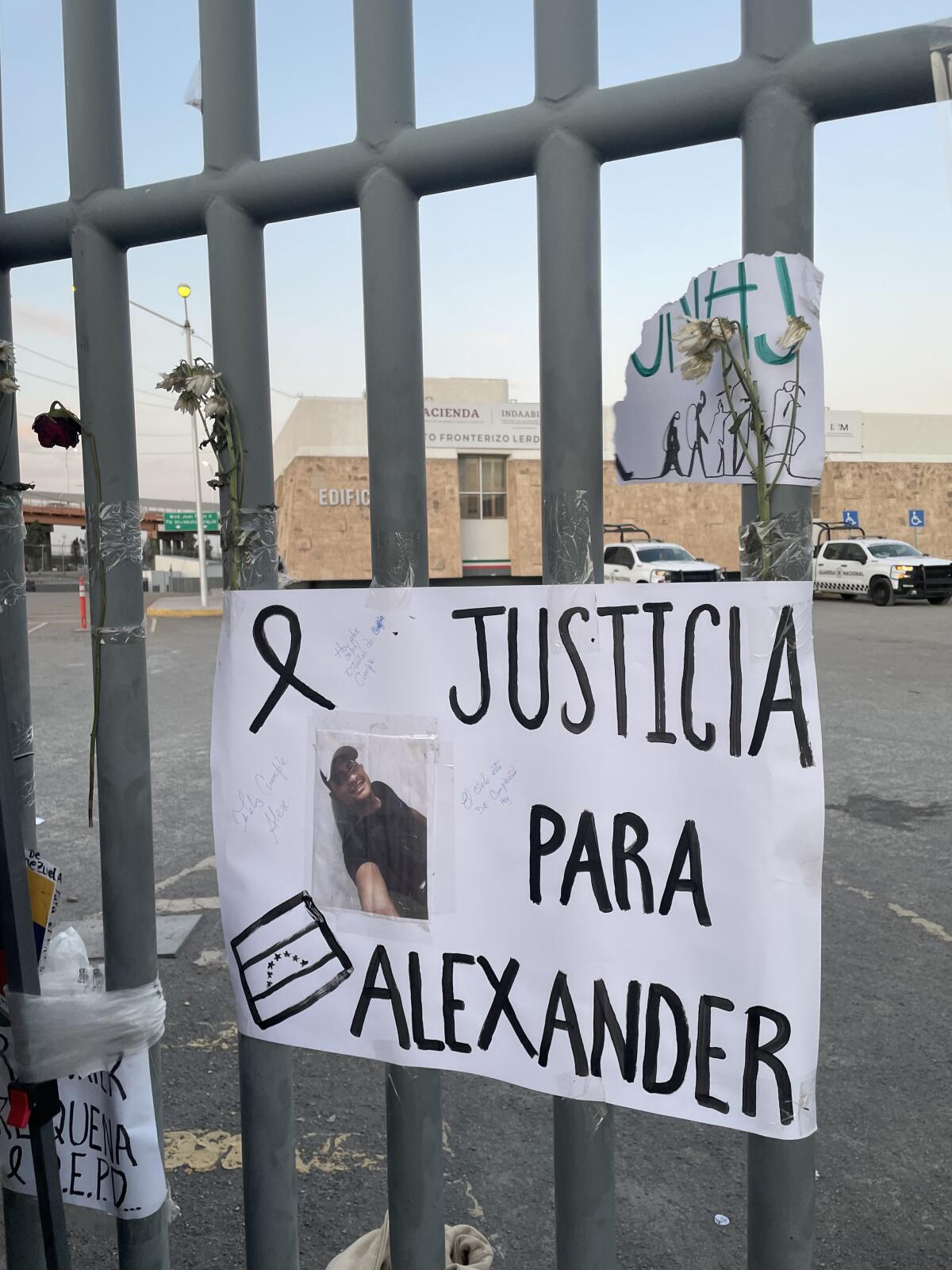

CIUDAD JUÁREZ, Mexico — They came to offer a serenade for Joel Alexander Leal Peña, born 21 years ago.

“¡Tus amigos llegamos aquí!” sang some three dozen people, clustered in the shadow of metal bars fronting a government building in this border city. “All your friends have arrived here!”

They held up cellphones to share the moment with loved ones a continent away as they repeated the words of a spirited South American birthday ballad. “We want you to be filled with happiness!”

Some had tears in their eyes.

Leal Peña, a native of Venezuela, had died days earlier, just shy of his birthday.

He and at least 38 others perished in a fire Monday at an immigration detention center just across the Rio Grande from El Paso. Now the bunker-like government building formed a haunting backdrop for the performance — both birthday observance and farewell.

All the dead and the dozens injured were natives of Central and South America, including at least seven Venezuelans. The fatality ledger so far also lists 18 from Guatemala, seven from El Salvador, six from Honduras and one from Colombia. Authorities said they all succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning.

They were among the thousands of migrants marooned here and in other Mexican border towns hoping for a chance to enter the United States.

With migration a politically charged issue north of the border, U.S. leaders have endeavored to offshore to Mexico the task of keeping migrants out. But this latest tragedy again dramatized for many how Mexico is ill-equipped to handle the influx of U.S.-bound migrants transiting the country.

“We’ve become the gatekeepers for the United States,” said Coni Gutiérrez, a longtime immigration activist here. “But Mexico isn’t prepared to be the guard dogs for any country.”

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador promises the investigation of the fire that killed 39 migrants will “find out what really happened.”

It’s still not publicly known if any of the victims of the fire had been sent back to Mexico from the United States under Title 42, a public health measure invoked during the pandemic that allows U.S. officials to expel migrants expeditiously without giving them a chance to file for political asylum or other potential relief.

Mexican authorities have labeled the deaths as homicides. Leaked security footage showed staff members at the facility hastening away as smoke and flames gathered and prisoners remained trapped behind bars.

Officials have filed homicide charges against three federal immigration agents, a private security guard, and a Venezuelan detainee — who, prosecutors allege, helped start the fire by setting a mattress ablaze during a protest about a lack of drinking water, food and other staples at the facility. Authorities expect more arrests.

The calamity on the border has stunned Mexico, a nation that has long sent multitudes of its own into the United States.

“I have to confess, this has pained me deeply. It has damaged me,” Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said Friday. “It broke my soul.”

At least 38 people died in a fire late Monday at a migrant detention center in Ciudad Juarez, across from El Paso, officials said.

But there’s not much sympathy for the president or other Mexican officials to be found here, among the migrants trying to eke out a daily living as they wait to cross into U.S. territory and file petitions for asylum or other relief.

López Obrador flew to Ciudad Juárez on Friday in a trip planned before the fire, but resisted pleas that he visit some of the victims still being treated in hospitals here.

A vocal contingent of migrants, mostly Venezuelans, has planted themselves outside the squat federal building where the fire occurred — situated between two bustling international bridges. The charred entrance of the lockup faces the Rio Grande, about 100 yards from the border.

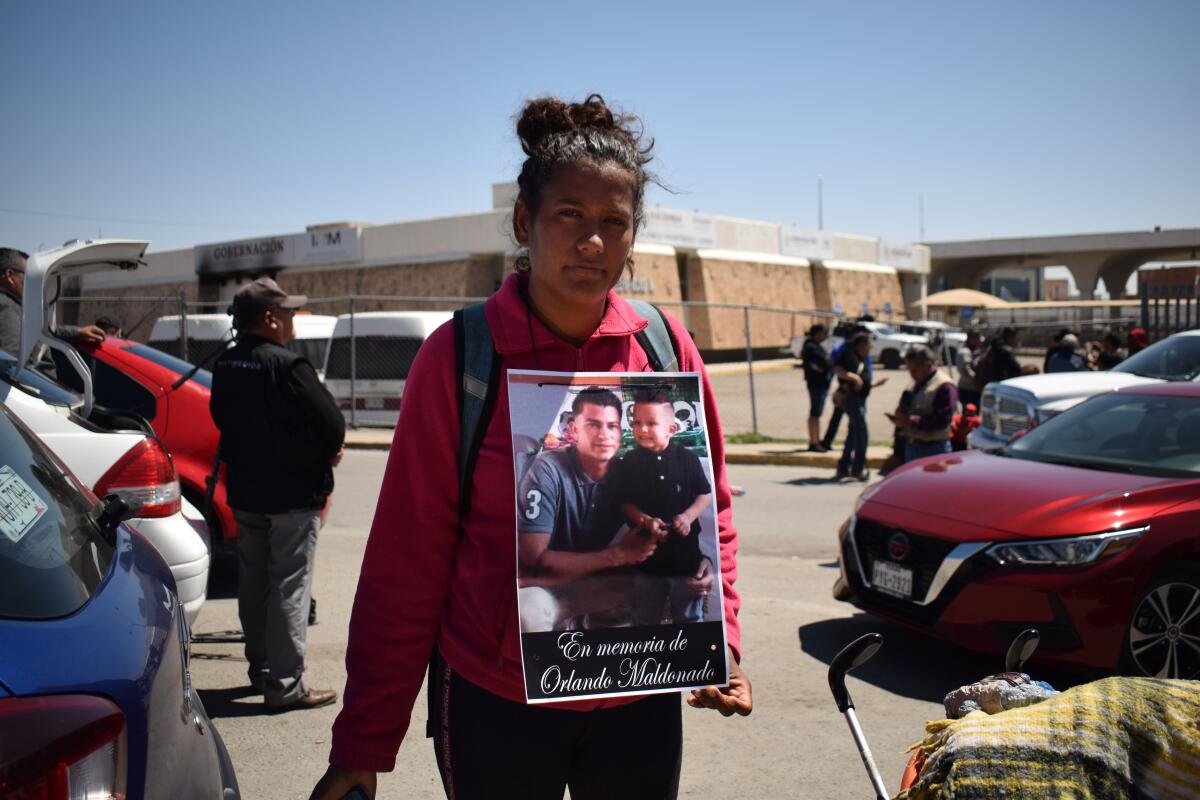

Some migrants near the site wear placards around their necks that bear photos of individuals lost in the fire. They all speak of seeking “justice” in the case, and fear that Mexican authorities may place the blame on lower-level officials and on Venezuelan migrants accused of starting the fire.

Signs with slogans such as “To emigrate is not a crime” and “End xenophobia” hang from the thick metal bars surrounding the government building. Migrants and activists have turned a stretch of the adjoining street into a hybrid tent city, protest site and memorial. Some 50 people now sleep here, in the shadow of City Hall.

Candles, flowers, photos of the victims and flags of their homelands mark a makeshift sidewalk altar and shrine for the casualties.

This is where migrants gathered to honor Leal Peña on Thursday, the day he would have turned 21.

They sang “Tu Cumpleaños,” penned by Diomedes Díaz, late maestro of the Colombian folk genre known as vallenato. They clapped to the beat, danced in place and belted out the familiar lyrics as a boombox provided accordion and percussion licks.

Leal Peña’s youthful face stared down at them from behind. A poster taped to the compound bars featured a photo of him and the demand: “Justicia para Alexander.”

The singers concluded: “I hope you are full of happiness and give thanks to God because you have reached one year more.”

Leal Peña was a young man determined to transcend his humble origins, to find opportunity outside his troubled homeland, his friends said. Like so many others, he had traveled for months and covered thousands of miles traversing jungles, mountains and deserts to arrive on the precipice of what seemed a new, and promising, life. His compatriots here could relate to all that.

Amid record-levels of border crossings, President Biden visited the U.S. border with Mexico on Sunday, his first trip to the region since he took office two years ago.

“I met Joel Alexander here in Juárez in a park,” said Jorge Luis Benites Méndes, 35, a Venezuelan wearing a blue-and-white Dallas Cowboys jacket who grabbed a microphone and played the part of front man in the birthday salute. “Really, we are all brothers. We’ve all been through a lot. … He was a calm person. But he knew how to try and get money for food.”

Leal Peña was among the many young Venezuelans who cleaned car windows and hawked cigarettes, snacks and other items to motorists in Ciudad Juárez. Their seemingly expanding presence upset the city’s mayor, Cruz Pérez Cuéllar.

“Our patience is running out,” the mayor told reporters on March 13.

That was a day after hundreds of migrants, mostly Venezuelans, rushed one of the bridges linking Ciudad Juárez and El Paso, forcing a temporary shutdown of the span. They were responding to rumors that U.S. officials were opening the crossing to them.

The mayor, a member of López Obrador’s ruling party, accused the migrants of harassing residents, even of assaulting women, and urged people to refrain from giving them money. The mayor outlined a plan — still not implemented — to find shelter and jobs for the growing ranks of foreigners, some of whom sleep on the streets and beg for food and cash.

On Monday, migrants and activists say, Mexican immigration agents, working in tandem with municipal police, swept dozens of migrants off the streets. Most were taken to the immigration lockup.

“I would call it an operation of death,” said Benites, the friend of Leal Peña. “They arrested Joel Alexander and others that day, but they had committed no crime. Migrants arrive here every day, and no one gives us work. What is one supposed to do? Die of hunger?”

Also picked up that day on the streets of Juárez was Abel Ortega Oviedo, 29, along with his wife, his two children, and his close friend, Orlando José Maldonado Pérez, 26. The two men were like brothers. They had traveled together for most of the treacherous route from Venezuela to Juárez, Ortega said. During the five-month journey, they paused — in Panama, Costa Rica, elsewhere — to find work.

“We shined shoes, cleaned car windows, sold cigarettes — whatever we needed to do to survive,” recalled Ortega, sitting outside the government compound that housed the ill-fated immigration holding pen. “We did everything together. He was my brother.”

They arrived in Juárez two weeks ago, said Ortega, who came with his wife and two children. Maldonado’s wife and 5-year-old son remained behind in Panama, with the hope that the family would reunite once he entered the United States.

Like other stranded migrants here, Ortega said he had tried, unsuccessfully, to secure an appointment with U.S. immigration officials on Washington’s smartphone application, CBP One. Many here complain of glitches in the system.

Ortega said he and his family were released from custody Monday afternoon — apparently because they had their children with them. But Maldonado remained in the lockup. Ortega returned to the hotel where he and his family — and, usually, Maldonado — were staying.

That night, his 4-year-old son had a question: “Papá, where is my uncle?”

Ortega told the boy his tío had to work and would be back soon. He had no reason to think otherwise — periodic arrests by immigration officials and police were part of the texture of life for the migrants on their odysseys north.

The next morning, an agitated friend arrived at Ortega’s hotel with the news: “Migration burned down!”

Ortega ran to the immigration facility, by then charred and emptied of prisoners. He embarked on a frantic search to find Maldonado.

“I went from hospital to hospital and was told he wasn’t there,” said Ortega.

Finally, on Wednesday, officials released an official roster of the dead. Maldonado’s name was on the list, his body at the city morgue.

Since, then, Ortega has been trying to find a way to get the body released and returned to Venezuela. It’s a complex process, especially since most of the dead do not have close relatives here. He and others have sought legal authorizations from grieving parents and other relatives in Venezuela in a bid to have the remains handed over to them.

“I want to see my brother, to hold him, to embrace him, to cry with him,” said Ortega, seated at the foot of the bars protecting the government compound. “I’m asking for nothing more. Just that they give him to me. Even if it’s just his ashes.”

Distraught, he rose and turned toward the blackened entrance of the detention center, just visible in the darkening evening. Sobbing, he began a conversation with his lost friend.

“Why, brother?” he asked.

“¿Por qué, hermano?”

Special correspondents Gabriela Minjares in Ciudad Juárez and Cecilia Sánchez Vidal in Mexico City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.